Originally published on Autos.ca on June 30, 2015 (Feature: Lotus F1 and Microsoft Dynamics)

Formula One’s a fast-moving blur, an expensive machine / that shoots down the straightaway. / And then is heard no more: it is a tale / told by hydrocarbon exhaust, full of sound and fury, / signifying obscene amounts of cash money.

– with apologies to William Shakespeare

I squinted at the invitation in confusion. Lotus F1 and… Microsoft Dynamics? You may have heard of Microsoft Dynamics, most likely in the thrilling context of accounting, auditing, and inventory management. Enterprise Resource Planning, or ERP for short. There’s also Microsoft Dynamics CRM (Customer Relationship Management) – sales, marketing, service, that kind of stuff. If there’s an obvious connection to Formula 1, I wasn’t seeing it. In my head I was imagining pie charts and sales projection slideshows decorated with racecar clipart.

I’m not a motorsports guy. The first time I stumbled across NASCAR when I was channel surfing, it was the Daytona 500 and I was utterly bereft: “So it’s a road trip, but on an oval track?” I could only imagine the skill and expertise that goes into driving at those velocities, and the stamina required to maintain that level of performance, all the while subjecting the body to temperatures and g-forces that would break lesser humans. But I’m the kind of person who watches figure skating for the spills. It’s not all Schadenfreude; it’s just a better spectacle.

I am, however, a spreadsheet person. To this day I wonder if I didn’t miss my true calling as a Red Bull-guzzling Excel monkey (and then I look over at the finance guys and nope, nope, nope, I’m much happier where I am). But show me a cell with a formula as long as a Shakespearean sonnet and I’ll openly weep tears of awe and wonder (or horror, because formulas really shouldn’t be that long).

So I said yes to the invitation, and now I get motorsports. I’m not sure how that happened.

If I were a better student of history, I’d have been able to tell you that the partnership between Lotus F1 and Microsoft was formed back in 2012 around when the Enstone-based team made its debut under its current name. The implementation of Microsoft Dynamics software began as you might expect, in budgeting and payroll. So far, so Monday morning office meeting.

It was the next phase that changed everything for Lotus F1.

Though Formula 1 is heavily regulated – indeed, skirting the myriad rules and regulations is a sport in itself – teams are still free to throw scads and scads of money around, especially if you’re backed by a soft drink company that consulted an Italian dictionary in order to field not one but two F1 teams. Lotus F1, on the other hand, is not backed by a soft drink company and does not have that kind of pocket change. (Well, to be entirely fair, it’s Formula 1, so we’re still dealing with an immodestly grand budget.) This means they have to very careful in order to make the most of their relatively restricted spending power.

Restrictions abound in Formula 1: fuel restrictions, tire restrictions, wind tunnel time restrictions – there’s even a limit on the number of calculations that the aerodynamics simulation processors can perform in a second. One slip-up at the start of the season can spell disaster for even a seasoned team. Which is where Microsoft Dynamics comes in.

The Lotus F1 team was used to doing things old-school – manually tracking everything with a pile of Excel spreadsheets. While this system worked for them in the past, it required a great deal of diligence and discipline to maintain. In addition, keeping all of this data in separate files created a major weakness: they couldn’t see the bigger picture. Put another way, they had all the data at their fingertips, but no way to effectively extract useful information.

For a well-heeled operation, this lack of information would not pose a significant challenge – incredible things can be achieved by simply brute-forcing your way past a problem with money. Last season’s nose cone deemed too evocative of a European beach in the summer? No problem, let’s manufacture twenty different designs and see what shakes out.

The smarter, more pragmatic approach would measure twice and cut once, so to speak. There’s no point in manufacturing a part that will never make it through testing. The fabrication queue can therefore be reduced to a small handful of prototypes. Or, to go even further upstream, will this part affect the aerodynamics more than a redesigned rear wing? No? Let’s focus on the latter then.

With a proper ERP system in place, these questions can be immediately answered. The old way would have involved physically getting up from your desk, marching over to another department, and sitting down for a five-minute chat with a couple of spreadsheets open just to figure out if your current project has any chance of seeing the light of day. Now, Lotus F1 engineers always have this information in front of them, and this transparency allows everyone – engineers, managers, executives alike – to take an active role in the decision-making process.

Another example of data vs information: whenever the racecar is out and about, sensor data from the track is immediately copied to computer servers back in Enstone. If there is a breakdown, the sensor data leading up to the malfunction is analyzed and that pattern can be used to predict similar problems in the future, allowing the crew to recall the driver and replace the offending part before any drama plays out on the asphalt. That’s more than economics, that’s lives at stake.

Curiously, Microsoft and Lotus F1 describe their relationship as a partnership, so what’s Microsoft getting out of the exchange?

Software development, especially at the enterprise level, tends to be slow-moving, with various checks and balances to ensure that changes in one part of the code do not break other components of the software, or have a ripple effect that introduces undesirable variations in output (e.g. “We just upgraded our software and now it says our entire 2016 strategy is wrong”).

F1 development is anything but slow and steady – ten different designs may be coming down the pipeline, all waiting to be tested, and any delay in decision-making costs the team precious time. It’s a demanding environment, one that calls for agility, responsiveness and rapid iteration – code is quickly implemented and just as easily discarded.

For Microsoft engineers, it’s a rare use case that allows them to observe immediate effects in response to their code in the ultimate stress-test environment; for Lotus engineers, it’s rapid, continual refinement of the backbone of their workflow. To return to our earlier example, testing of one design may be put off in order to provide wind tunnel time for another part that will have greater effect on the aerodynamics of the racecar. Because this kind of decision can now be made without bogging down the development with housekeeping, engineers can focus on what they do best – making the fastest racecar they can.

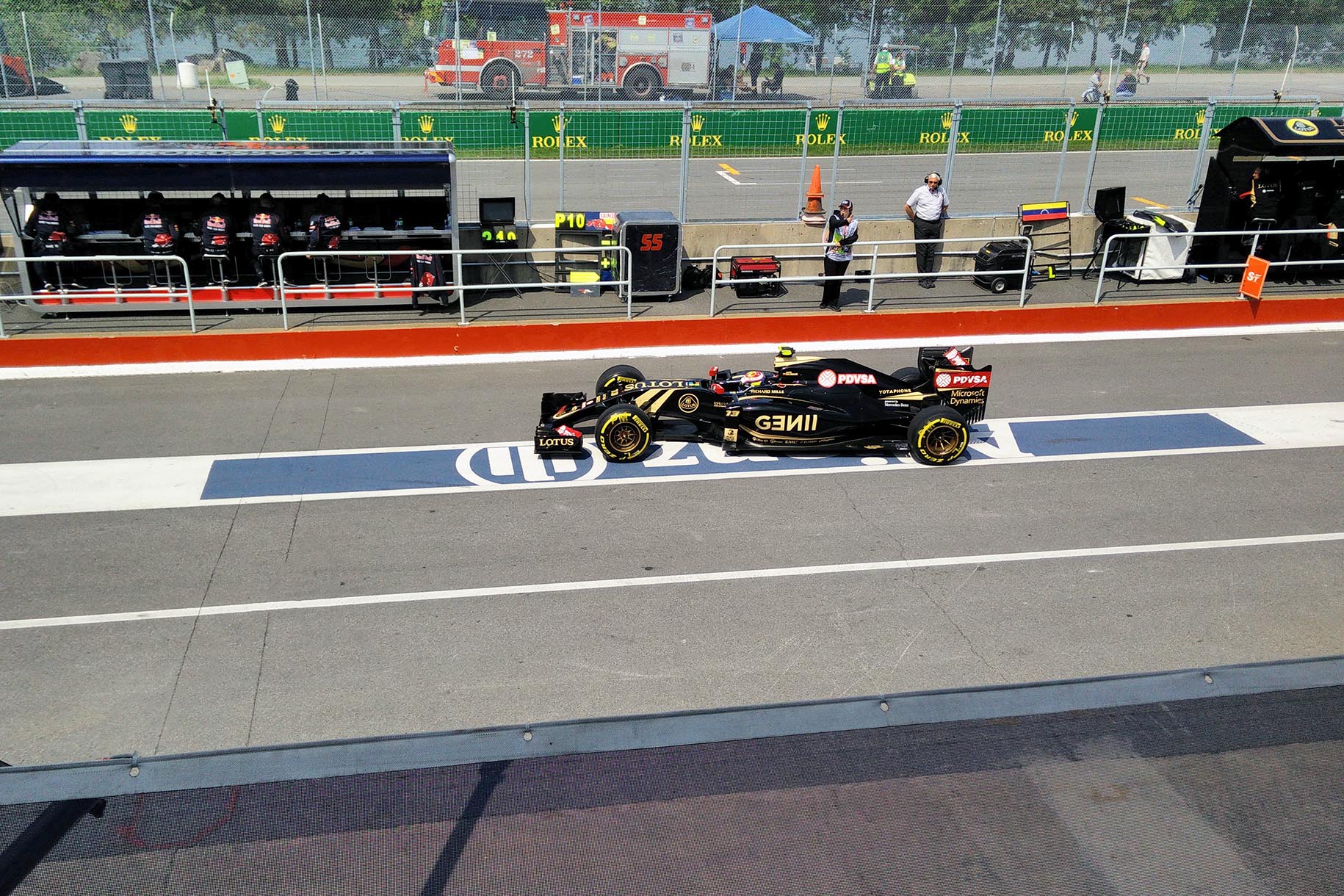

While I was in Montreal, I visited the paddock where the crew and engineers were preparing for the day’s practice sessions. Once I got over the initial whiff of “What’s on fire?”, I noticed something: everything happens at once. When it came time to assemble the racecar, one person slid underneath the raised chassis with a flashlight as others came in from the warehouse with components, performing precise surgery on a chassis that was being lowered even as they worked, two crew members at either end operating the lifts as two others removed the chocks, and yet others approached with body panels and tires, tape and power tools.

As many as twelve people were gathered around the car at any given time in this carefully choreographed chaos. IKEA amateurs need not apply. Hell, I don’t think I know enough prepositions to describe how everything fit together, much less how it’s taken apart. Watching the seamless collaboration between the individuals in this well-oiled machine, it’s a beautiful thing.

Even here, there’s an incredible amount of accounting going on: tires have their barcodes scanned by no fewer than three different people representing three different organizations whether they’re coming off the vehicle or being installed, in order to track their mileage; those parts I used in my earlier examples, they’re all tracked with barcodes, each with their own replacement schedule. The software tells the team not only when to swap them out, but also when to fabricate so that they can ship it to the racetrack in time. Just-in-time, if you will.

There’s one image that’s stuck with me since that weekend. It’s just after 2 in the afternoon, storm clouds in the distance promising rain, nobody knowing exactly how much, despite the dedicated radar. The practice session is underway, but a caution over the course means Grosjean and Maldonado are sitting in the Lotus paddock, waiting on a call that will see them either wrapping up in advance of the rain, or hitting the track to knock out a few more laps. The crew is tending to the tire warmers and brake coolers, the drivers are watching footage of their previous laps on monitor rigs perched in front of their cockpits, while others are indulging in a bit of coffee and shooting the breeze. It’s about as close to “day at the office” as you’re going to get on a racetrack.

Then the call comes in and the crew springs to action. Monitors are moved away, safety helmets put on, tire covers taken off. It’s all hands on deck as the cars are rolled out into the pit lane. A shadow falls over the interior of the paddock, echoing the hush that’s come over the assembled cast as they take their positions in front of the paddock doors. The cars, the drivers, the crew, the engineers – the team – stand at attention, their stark figures striking out the midday sun. Beyond them, nothing but the sky above and asphalt below.

Time to go racing.