“That car should be at home!”

There was an elderly gentleman beside me, grinning widely from the seat of a Chrysler 300 SRT8, at a set of lights near Conner Avenue and 8 Mile Road in Detroit. It was November, and a sopping wet Friday morning just after 7:30 a.m. I was in my Dodge Viper: a 2000 GTS Coupe. Black with grey stripes. This was the second time I’d ever driven it in any sort of precipitation.

“You gotta' get her inside!” the man encouraged, still beaming, and still shaking his head. We were Mopar buddies at that moment, in the cold and wetness, right in the neighborhood where our respective rides have their roots.

“I know,” I replied, returning the contagious grin. “It’s not so great in the rain.”

Heavy winds had blown the fall leaves all over, and they blocked sewer drains and caused deep flooding to portions of the beaten-up roads. It had been pouring, biblically, for an hour or more – only just letting up recently.

Driving a 2000 Dodge Viper GTS on a cold and rainy November morning is as stupid and dangerous as mowing your lawn in open-toe roller skates. You’d need to be precise, exact, and very careful. One wrong move, and there could be a real mess.

And, like some of its vintage, my Viper isn’t entirely waterproof. Mainly due to the tendency of the hinges to shift slightly as the car ages, the doors sag a touch, reducing pressure between the window and weather seals and letting an occasional lick of water past the glass and onto my leg. Part of my springtime maintenance ritual includes re-adjusting the doors, which sag back down again by the end of the summer.

It’s part of the charm.

8 Mile Road and Conner Avenue have been home to Conner Avenue Assembly, aka, the birthplace of the Dodge Viper, for over 20 years. Chrysler bought the building from Champion in 1995 and turned it into a specialized assembly plant. At 392,000 square feet, the former spark-plug factory looks big, especially next to a residential neighborhood. Thing is, it’s more of a workshop than a factory, and a fraction of the size of a typical automotive mass-production facility.

Connor Avenue Assembly is 9 hours from my current home in Sudbury, Ontario, but only about 20 minutes and a border crossing from the neighbourhood in Windsor, Ontario, where I was born, and where I spent my early years.

I grew up near here. I became a car guy, just down the street, through the tunnel, and around the corner. Pre-teen me would make my dad chase down any Dodge Viper I spotted with the family minivan so I could hear it. I’d pursue Vipers on my bicycle for a closer look, too. By age 15, I had a box of magazines, brochures, and any literature I could get my hands on about the big, brutal beast from Michigan. Hell, when delivering the evening paper for some extra cash, I’d entertain myself during the boring hour-long walk by thinking of driving my very own Viper, one day.

Was it the blue and white striped colour scheme? The voice of my childhood hero, Jim Scoutten, going up a notch on the excitement scale when he talked about the Viper on Motor Trend Television? The great big numbers and specs that bested virtually any competitor in its day? Whatever the reason, the Viper bit me in my formative car-guy years, just minutes away from where it’s built.

And today, in the cold and the wet, I was taking mine back home, to meet some of her makers.

That home is accessed via a winding driveway, a security gate, and a simple walk into the front doors. It’s no more complicated to get inside of than a Walmart. And inside, despite building one of the most raucous and extreme performance cars going, Conner Avenue Assembly is a tidy and civilized place.

As an owner, I love, live with, and cherish the purely mechanical, no-BS, and raw feeling of the Viper. The footwells overheat on long drives. The exhaust drone is thick through the cabin. The steamroller tires grab every imperfection in the road, so the car is constantly squirming around beneath you. It’s an exhausting machine to drive in many ways, and it’s not for everyone, but it all makes the Viper a special car.

I wanted to see validation of that in how they’re built. I wanted to see a factory full of smoke, welding sparks, greasy floors, workers yelling, and metal clanging and smashing. And maybe, a guy using a sledgehammer. When you drive a Dodge Viper, you’re pretty sure that, somewhere in the assembly process, a guy in overalls, smoking a cigarette, and using a sledgehammer, is involved.

But instead, Conner Assembly is bright, airy and comfortable. It’s quiet – there isn’t so much as a hum from the overhead ceiling lamps. The temperature is perfect. Big fans move air around the building too, so there’s always a breeze. It’s tidy and neat and clean and organized.

There are no welding sparks, as the Viper’s hand-welded frame structures are fabricated off-site and then sent in. No grease, and no smoke. The heat and noise and welding all happens elsewhere: at Conner Avenue, components are collected, assembled, combined, and turned into Vipers.

The plant is set up with dozens of stations surrounding a central parts store. It’s sort of like a restaurant fridge, but filled with trim panels and seatbelts and manifolds and brake rotors, not sauces and vegetables. In the same way a cook visits the fridge with a recipe and a cart to gather ingredients for the day’s specials, Viper’s builders visit the parts store with giant carts, and their work orders, gathering the ingredients for the builds of the day.

There’s Heidi Lafleure, who pulls large, lightweight magnesium ‘front of dash’ structures from a rack, installs them to a machine that locks them stationary, and sets off fastening the appropriate pedal-sled, brake booster, and other hardware procured earlier in the parts store. Her Wi-Fi enabled torque wrench auto-tightens bolts to the correct level as she installs the hardware, and it knows, and tracks, which bolt it's being used on. Heidi can cross check everything on a computer display before sending her assembled dash to the next station, where Darrel Dodds installs and routes numerous wiring harnesses throughout the assembly.

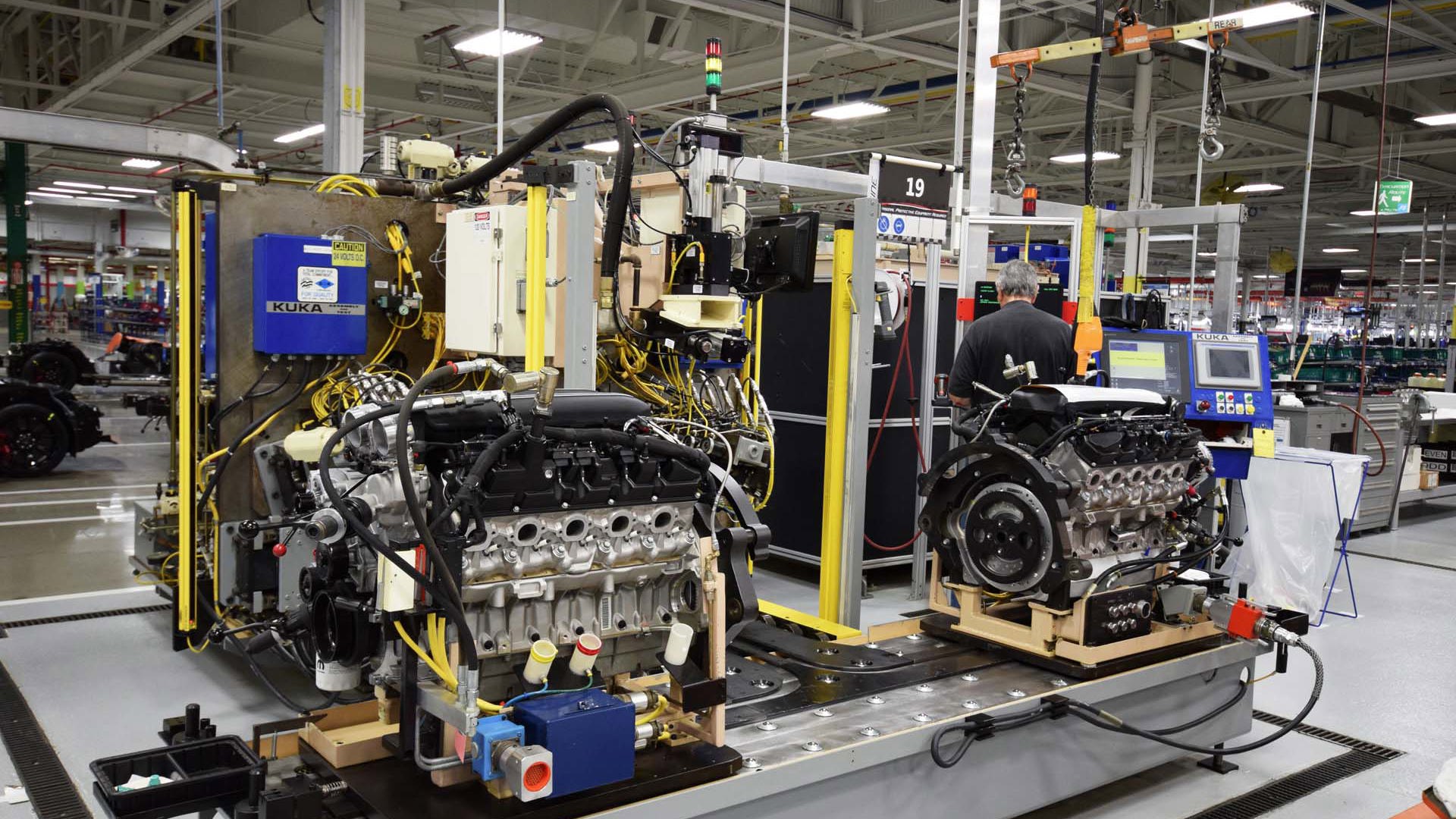

Building up the engine requires teamwork. Viper’s big V10 engine blocks come in from a supplier, are cleaned and dried by the engine builders at Conner, and then assembled. It’s sensors first, then wiring, then pistons and rods, then pushrods and the camshaft, rockers, covers, spark-plugs, manifolds and the like, all fixed and attached by a few people, working with smiles, under bright lighting.

Angella Richberg, an avid photographer as curious about my wide-angle lens as I was about her pushrod install procedure, adds some lubrication, drops the pushrods into their shafts, and repeats for all 20 rods, smiling all the while. She walks around the engine, inspecting it. She looks happy, and I’m delighted to see my first Dodge Viper engine not surrounded by Dodge Viper. It looks smaller when it’s not jammed into a tiny car.

Richberg’s co-worker, Greg Rinehart, hooks up larger external parts to the engine, including the timing cover and water pump provisions, before its initial test.

“The engine block in your car, and the pistons, are similar,” Rinehart tells me me, hooking up a wiring harness to the oil pressure and coolant temperature sensors. “The manifolds are different, and the new engine has plastic valve covers, where yours are metal. It’s more powerful now, but the engines are really pretty similar in many ways.”

“Would you have built my engine?” I asked. For model-year 2000, the Conner staff built about 950 copies of the Viper GTS, of which less than 95 were Canadian-spec, like mine.

“Oh, probably. Yup. Almost definitely!” he replied with a proud smile.

These folks know they build something awesome, and take pride in it.

With his engine completed, Rinehart wheels it over to the cold-test machine, which checks for proper plug gaps, any signs of gasket leaks, the continuity of the computer systems and sensors, and runs nearly 900 tests in total on the engine before it gets filled with fluids and put into the car. The cold-test machine is a ghastly assembly of cables and wires and plugs like something out of a horror movie, and it’s said to be extremely picky.

Once the cold test is passed, engines are installed in the partially completed cars, which arrive at Thomas Ballard’s station. Ballard and a partner install wheels, and bring the Viper to life. Fluids and fuel are pumped in. The air conditioning system is charged. Tire pressures are adjusted. The computer system is initialized, boots up, self-checks, and displays a bunch of diagnostic information on screen that the owner will never see. It’s all activated, and now, the Viper is a complete, working car — albeit missing most of its interior and all of its body.

At this stage, a Viper looks like a sinister go-kart, and Ballard drives it onto a dyno roller, secures the car, and accelerates hard, several times, while computer monitors watch. Winding up a skinless Viper sounds like fun, though Ballard is stone-faced. He stares intensely at a TV screen overhead, watching data stream across and looking for any issues. Sensors, power output, fluids, and other parameters are checked, as Viper’s engine is given its first hard workout, just moments after firing up for the first time.

I met Jill Braunschneider next, who begins applying fasteners and bracing to the rolling chassis to prep it for body panel installation. She wheels around the Viper in a chair as she installs special clips that help secure panels to the frame beneath.

“You should get one of these,” she tells me, beaming. “It’s the ACR Extreme.” She’s focused on installing various fasteners to the understructure that supports the bumper, but pauses to show me the suspension. “Look at those adjustable shocks, and the brakes, too. This thing is serious. You should get one. It’ll be a nice upgrade from your 2000.”

Doors go on next, along with bumpers and other body panels. Remember earlier, when I mentioned my door-sag problems? Hilariously, my tour guide, Jim Richards, was likely the fella who installed one, or both of the doors to my car when it was built. I asked him about the fussy sagging hinges on early Viper GTS models.

He responds with a chuckle. “The engineers were really focused on keeping the car light,” he explained. “So, back then, they used an aluminum hinge. We wanted a steel hinge, since it’s stronger, and I fought for it, but lost. We had to go with aluminum, so we even pre-sagged the hinges with a 200-pound weight before setting the door adjustment. It’s really fussy. Eventually, we switched over to a stronger steel hinge, and now, the doors are an awful lot lighter than the ones on your car, too.”

Today, Viper doors are made by superheating a thin sheet of aluminum, and shaping it with high-pressure air, not stamping, which would cause it to crack.

Next up? Jeremy Gonzalez and Anthony “Smooth” Thomas fasten bumpers, the hood, and the doors and other panels to the Viper’s structure. Taking the pre-manufactured body panels off of special racks and attaching them to the car, these fellas make the Viper start looking like a Viper.

Once complete, the cars move to a special inspection area. All of Viper’s body parts are painted and prepped off site by a company called Prefix, located a few minutes away, and shipped over by truck. Once the parts are fastened to the car, staff from both Prefix and the Conner Avenue plant meet under special flaw-revealing lighting in an inspection area. Bonnie Marth and Krystal Kozak go inch-by-inch over a completed Viper ACR, touching every panel and seam, moving their heads and squinting to see each part of the car from various angles.

“There’s some orange peel, here,” Kozak tells Steven Showalter, pointing at the rear edge of an ACR’s park-bench sized spoiler. Showalter inspects it, and returns a moment later with a buffing wheel and some compounds, works a moment to correct the issue, and then completes the polish by hand. Another car arrived moments later, with a tiny defect in the hood emblem circled in wax crayon.

The inspection process sees staff scrutinize each other’s work, playfully but with a serious tone. The various stages of buffing and polishing and re-inspection ensure all units are cosmetically perfect before being entering a climate-controlled room, which houses the vehicles until they’re transported to owners.

The room had a few dozen completed units awaiting shipment, with bright stripes, custom paint-jobs and every possible combination of wheel and caliper colour imaginable.

“That’s a lot of smiles,” I thought to myself, standing in the doorway of the pre-delivery room. This was a privilege – I wasn’t allowed past the doorway, but here sat several million dollars worth of hand-built American supercar, and I got to see a few dozen Vipers, custom-designed by their owners, before those owners did.

Owners are allowed, and encouraged, to visit the factory for pick up, too.

A purple ACR sat near the factory doors, just across from a bunch of retired racecars proudly displayed, filthy and covered in grass, brake dust and dirt. The retired race cars all look as though they just got finished kicking some ass.

And the purple new ACR, gloriously displayed across from its retired brothers and brand spanking new, was a customer pickup. The folks at Conner Avenue want customers to come see them. They want to show off the smiles, and pride, and expertise that go into each and every car.

“This owner is coming to pick his car up here, in a week or so,” Jim Richards tells me. “Some come see their car, and we ship it to them. Others come here, meet the people who built it, and drive it away. It’s almost like a family.”

It’s a family I’m proud to be part of – and a family I hope to visit again, to pick up my grey Viper GTS with white stripes, in that foyer.

One day.