In the realm of baseball, this year’s 2016 World Series is perhaps the most unlikely pairing imaginable, a newsworthy clash of long-suffering, drought-afflicted titans: the Chicago Cubs, who haven’t won a World Series since 1908, are playing against the Cleveland Indians, who haven’t won since 1948. Whichever team takes the win, it’s been a long time coming.

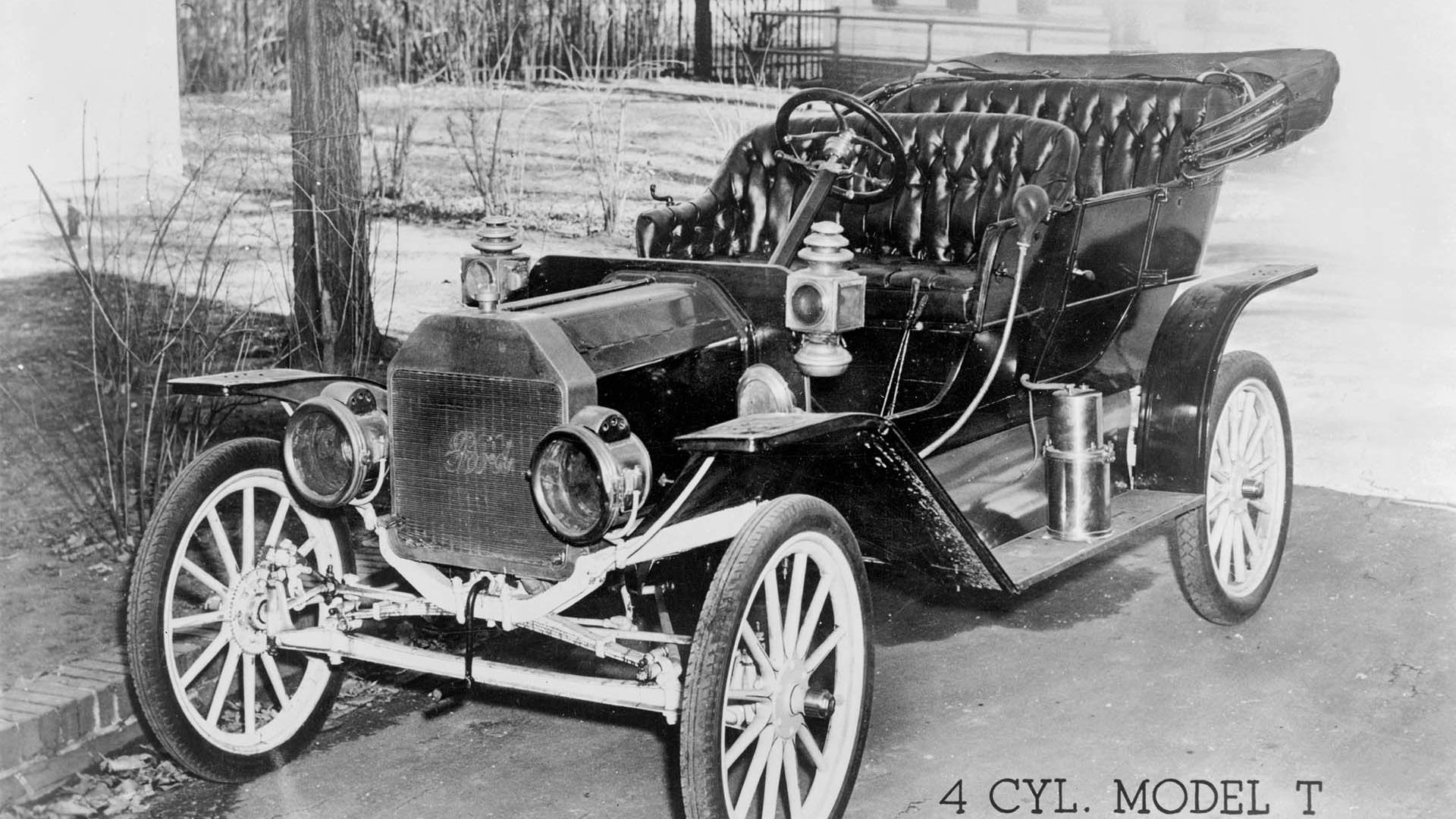

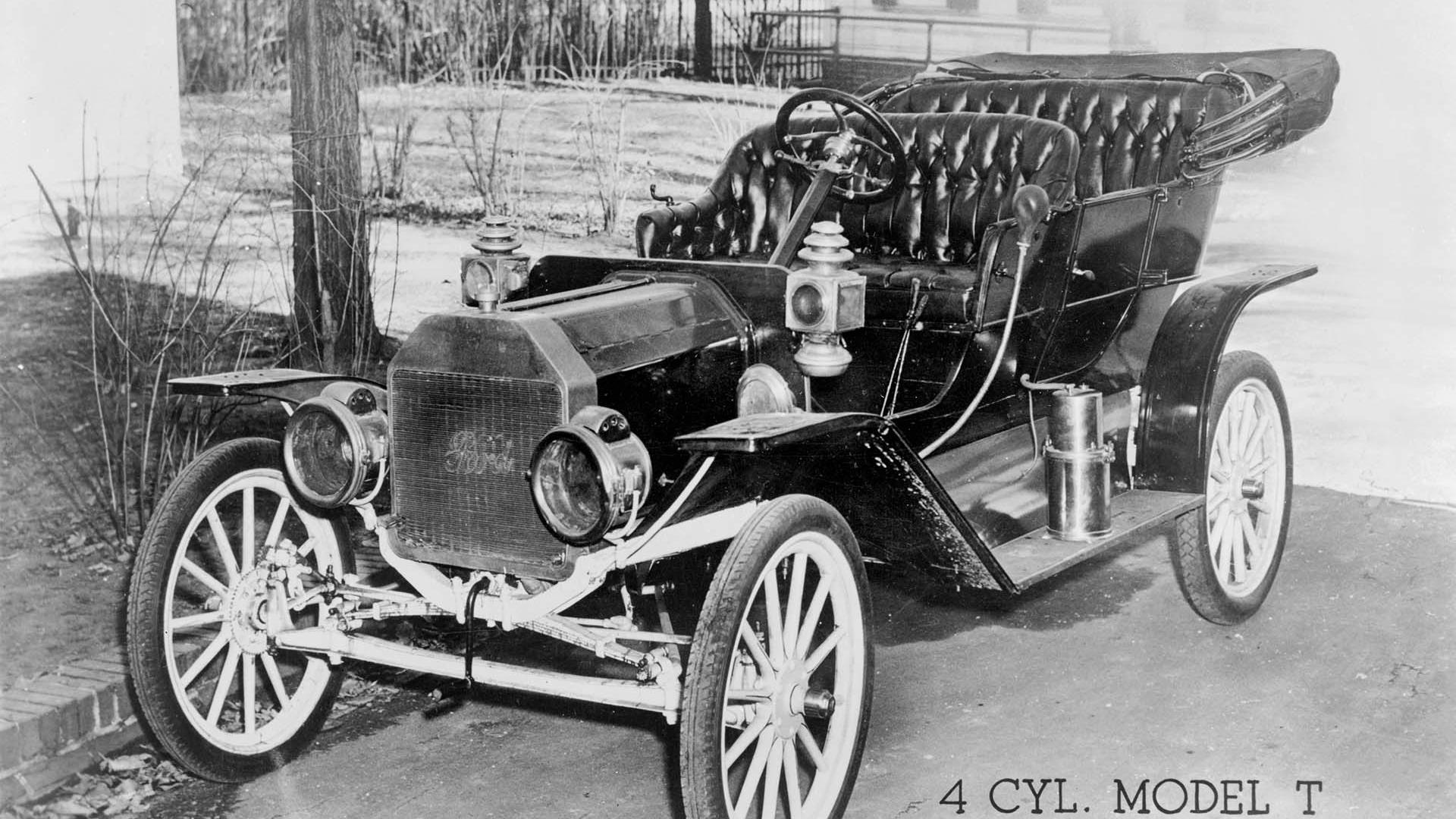

How long, exactly? Well, in automotive terms, when the Cubs went to bat against the Detroit Tigers in Game 1 of the 1908 World Series on October 10 that year, cars were still little more than self-propelled carriages with quirky, individualistic controls. The Model T Ford had been in production for exactly nine days (it went into production on October 1, 1908). Sitting US president Theodore Roosevelt had ridden in an automobile, but never owned one (William Taft, who succeeded him in 1909, was the first president to own an automobile, with one of his more notable cars being a Baker Electric).

Long-distance travel back then was accomplished by train or ships, and powered flight was just five years old, with Orville Wright having first flown on December 17, 1903 – coincidentally just two months after the first modern Major League World Series championship was played. In cities around the globe it was foot-power, horses, streetcars and subways that provided the backbone of urban transportation (the New York Subway, one of the world’s oldest public transit systems, opened in 1904).

Race start in New York City

Race start in New York City

Perhaps the biggest automotive news at the time was the running of the New York to Paris Race, billed as the first round-the-world automobile race. Inspired by the 1907 Peking to Paris Race, the New York to Paris Race got underway with six cars departing Times Square on February 12, 1908. The teams drove west across the US – often using “balloon tires” to straddle railroad tracks where there were no roads – then loaded their cars onto steamers and shipped them across the Pacific to Vladivostok, Siberia, the starting point for the drive across Asia and Europe.

Winning team in Thomas Flyer

Winning team in Thomas Flyer

The race continued for a gruelling 169 days and covered 16,700 km, with the winning American team – driving a Thomas Flyer – arriving in Paris on July 30. Only two other teams made it all the way: the Germans, driving a Protos, and the Italians, driving a Zust. The French entered three teams, but none of them finished. Hardly surprising, then, that the London Daily Mail proclaimed the motor car to be “the most fragile and capricious thing on earth.”

Fast forward to 1948, the year the Cleveland Indians last won the World Series playing against the Boston Braves. It was 40 years and two World Wars after the Cub’s historic win, and cars had become an integral part of life. Unlike Theodore Roosevelt 40 years before him, the US president of the day, Harry Truman, not only owned a car (a 1941 Chrysler Royal Club Coupe) but also had an official state vehicle (at the time the World Series was played, this was a modified 1939 Lincoln convertible with a 1942 Lincoln front end, affectionately known as the Sunshine Special).

Automotive design had made huge strides forward in the interval since the Cubs won the World Series, with features like closed bodies, integrated fenders, standardized controls, hydraulic brakes, automatic transmissions, tempered glass, independent suspensions and even (on some cars at least) seat belts making the cars of the era reasonably familiar-looking by modern standards – the iconic Volkswagen Beetle had been in production for three years (though it had yet to be exported to North America) and the Willys Jeep had already set the mould for what would become today’s Jeep Wrangler.

NASCAR was founded by Bill France Sr. in February 1948, but the big automotive story of the year was the brewing debacle surrounding Preston Tucker’s futuristic-looking but troubled Tucker 48 (also known as the Tucker Torpedo). The Tucker 48 was a novel rear-engine, rear-wheel-drive sedan featuring safety elements such as a perimeter frame, padded dash, a shatterproof pop-out windshield and a directional third centre headlight that steered with the wheels. Sadly, Tucker’s dream was destined for failure, and after a string of money-draining developmental and technical problems, only 51 cars were built in Tucker’s Chicago-based factory before the company was caught up in a financing scandal that culminated in a US Securities and Exchange Commission investigation and eventual bankruptcy.

The Chicago Cubs and the Cleveland Indians can likely both sympathize with poor old Preston Tucker, because both teams have seen their hopes dashed again and again. As airlines took over transoceanic travel from passenger liners, and jets replaced propellers, and touch-tone phones replaced rotary dials only to be replaced by cell phones, and home computers and the Internet sprang into existence and were then eclipsed by smartphones, and credit cards replaced cash, and cars sprouted disc brakes, fuel injection, emission controls, seat heaters, traction control, anti-lock brake technology, GPS navigation, automatic climate control, mobile Wi-Fi and everything else we now take for granted, morphing over the years from body-on-frame, front-engine, rear-wheel-drive sedans and wagons into a fleet of ubiquitous unibody, front- and all-wheel-drive crossovers – throughout all of this the Cubs and the Indians lost, and lost, and lost. And now one of them is set to win.

Actually, perhaps it’s fair to say that both of them will win, because while one will take home the Commissioner’s Trophy, the other will surely go down in the history books as the hardest-luck team on the planet. And that has to be worth something, doesn’t it?