They call it a supermoon, the closest we’ll get to our lone satellite for decades. Standing by a rumbling Camaro at a beach in Los Angeles, it looms huge and yellow on the horizon, further amplified by a trick of the atmosphere. Seventeen hours ahead in Tokyo, the sun is still up, but soon that same moon will beam down placidly as night takes over another busy city. In both places, it shines down on people who differ in country, language, and customs, but who are drawn together by a common desire: to do giant burnouts.

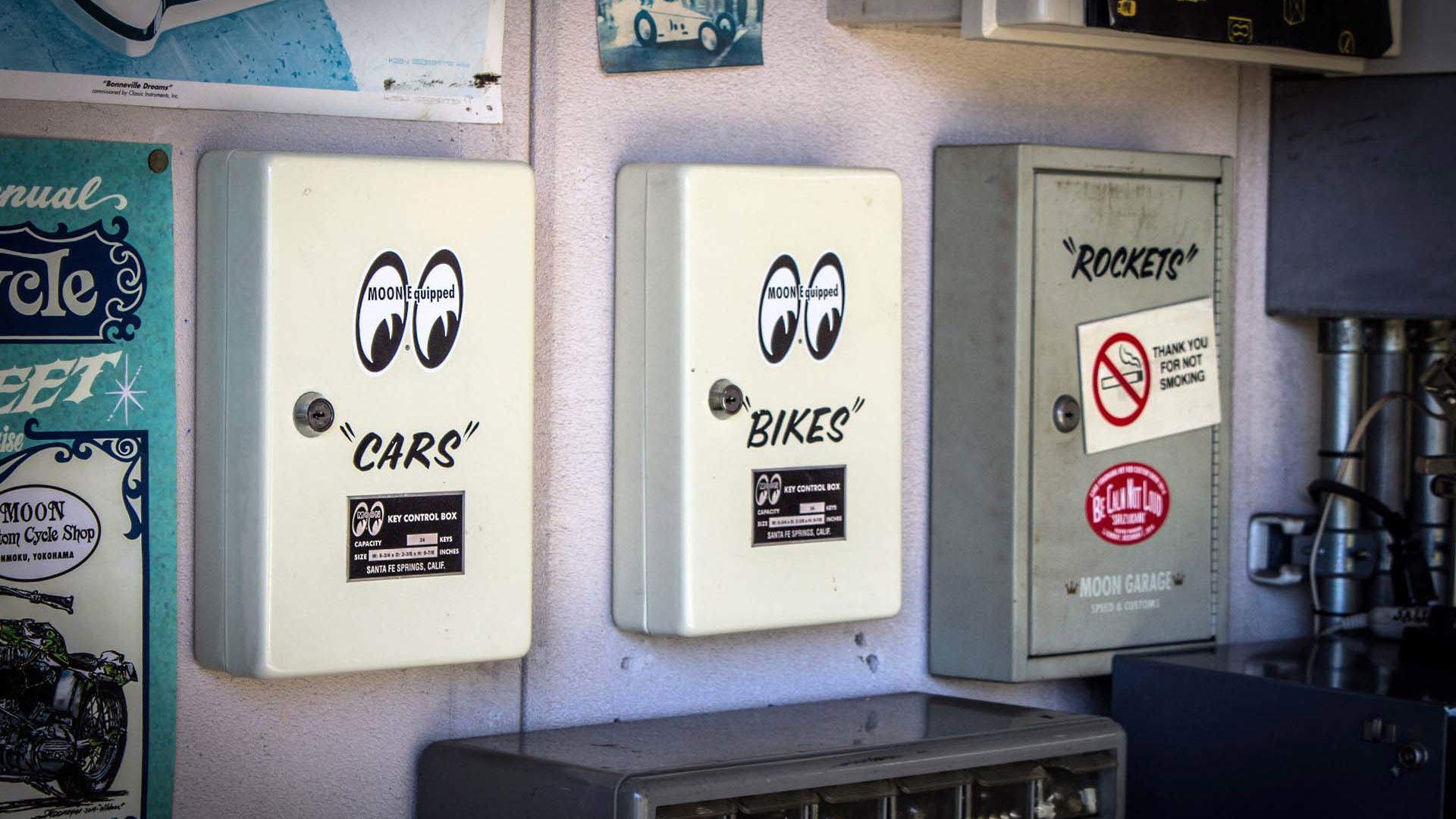

If you’ve ever been to a hot-rod show, then the stylized eyes and yellow face of the Mooneyes brand needs no introduction. If you’ve not heard of the company, hop in, we need to take a drive.

Up from the ocean, over the winding crest of Mulholland drive, and deep into the heart of Los Angeles proper. Battle the worsening traffic, then get out into the industrial areas, and hang a left into a parking lot watched over by a set of giant, stylized eyes.

Dean Moon was born in California in 1927, just missing being of age to serve in WWII (he would later serve in the Air Force during the Korean war). By the time he was in his late teens, returning US servicemen were starting the hot-rodding craze, and Dean was right at the forefront. He cut his teeth out on the Bonneville Salt Flats, where speed-freaks were figuring out ways to crank ever-higher levels of horsepower out of their V8-powered contraptions.

Moon was in the right place at the right time for an innovator and a showman. Like his eventual friend Carroll Shelby – Dean would one day help Shelby install a V8 engine into what would become the first-ever Cobra – Dean Moon understood that it wasn’t enough to just sell hop-up parts to gearheads. A touch of showmanship would go a long way.

Operating out of a garage out back of his father’s cafe, Dean found his niche. He started out selling parts and tuning engines, with one of his earliest efforts being a dragster made out of a 1924 Model T roadster. Called the Hunter Oil Special, it was painted with the number 00. Some jokester painted a couple of pupils inside the zeros, and a trademark was born. A few years later, Moon hired a Disney artist to redo the eyes, and created a style that would last sixty years.

The Moon Equipment company sold a number of products, from specially ground crankshafts to foot-shaped accelerator pedals. The two most-iconic items are probably the Moon tank and the Moon discs. The former is a spun aluminium fuel tank that looks a bit like a keg. Dragsters and salt flats racers only need to carry enough fuel for a couple of runs, and the Moon tank was flexible enough to be mounted anywhere, making custom builds easy.

The Moon discs were flat hubcaps that helped improve aerodynamics for the speed record cars. Even today, head down to Bonneville during speed week, and you’re sure to see cars running these simple but immediately recognizable designs.

After serving in Korea, Dean Moon returned to Los Angeles, and opened a larger shop at 10820 South Norwalk Boulevard. The operation is still there, and if you pull it up on Google Earth, you can even see the Mooneyes logo painted on the tarmac at the entrance to the building.

Moon promoted his products with custom dragsters and uniforms for his crew, and soon found his creations immortalized in Revell models and later Hot Wheels. He also documented the golden age of hot-rodding as he was an accomplished amateur photographer.

In 1969, Moon Equipment was a well-established brand, known for speed. However, the request that came next was something of a surprise: it wasn’t a team looking to set speed records or dominate at the dragstrip; it was Nissan, and they were looking to beat Toyota.

The Japanese Grand Prix was the largest and most important racing event in Japan. While it was eventually replaced by a stop on the Formula 1 circuit, for a time it was the battleground where Japanese automakers established who had the best engineering teams: Nissan could be smug in the knowledge that their R380 had been easily trouncing racing versions of the Toyota 2000GT.

But there was a problem. Toyota’s secretive division 7 was working on a racing machine built around a newly developed 3.0L V8. The R380’s 2.0L straight-six would become the beating heart of the Skyline GT-R legend, but it wasn’t going to be able to match the power of this new Toyota threat. With time running out on an unproven replacement engine, Nissan turned to Moon.

It would be the only time Nissan used a racing engine developed outside of the company. Moon supplied tuned 450 hp 5.5L Chevy small-block V8s, set up to handle the abuse of sustained revs on the racing circuit. Nissan fitted this American heart into their CanAm-style racing prototype, the hugely winged R381, and took home victory. The car still exists in Nissan’s heritage collection, tucked away on in a museum on the grounds of their Oppama engine factory.

Moon-built dragsters and salt flats racers continued to set records all through the 1970s, and the Moon shop was a hub for all manner of hot-rodders. “Grumpy” Bill Jenks ground cams and Fred Larsen fabbed up specialty parts; both names would become legends as salt flats streamliners carried their names into the record books.

Starting in the 1970s, a face you’d often see around the Moon shop was that of Shige Suganuma, a young Japanese exchange student. It was unusual for a Japanese national to hang out with old hot-rodders, especially as a lot of the old guard were former military men. However, Moon’s experience in Japan and the bright enthusiasm of Suganuma had Dean taking the young man under his wing.

Japan

Around the back of a cafe in Yokohama, I watch as Hiro “Wild Man” Ichii carefully applies pinstripes to the flank of a chopped and lowered VW Beetle. He looks like a rockabilly version of some 18th century Japanese calligrapher, and trained under famed customizer Ed “Big Daddy” Roth.

Ichii is one of the tight-knit staff here at Mooneyes Japan, an outpost of the original Moon company established by Suganuma in the 1980s. Shige learned a lot from the elder Moon, and built up a yellow 1969 Camaro Z/28 as a sort of apprenticeship of speed. He still has the car, which he keeps here in Japan.

The Mooneyes brand arrived in Yokohama to a burgeoning and perhaps hidden hot-rodder car culture. These days, Mooneyes still sponsors the annual Yokohama hot-rod show, but there’s a slight difference to the Japanese twist on the passion for speed. There are no salt flats out here, and you have to know where the dragstrips are. Most of modern Japanese traffic is a sea of identical, featureless boxes.

But if you pull back the curtain, there’s a whole segment of passion here, and most of it centres around Mooneyes. Just as the California shop was a hub for the golden age of hot-rodding, the Yokohama cafe is a place where you can show up on a morning and see all kinds of machinery out back, from Moon-disc-equipped dune buggies, to heavily customized motorcycles.

When Dean Moon died in 1987, he was just 60 years old. The business passed to his wife, but there was a brief hiatus for the company. Should the Mooneyes name be swallowed up by some larger corporate entity? In the end, the Moon family decided that Shige’s dedication to the spirit of Mooneyes made him the perfect leader for the company. Mooneyes USA and Mooneyes Japan operate on separate shores, in separate countries, but they are tied together by a shared passion.

As I climb back into the Camaro in California, and fire up its modern small-block V8, it’s good to know that some things don’t get lost in translation. We all look up into the same skies; we all live under the same moon.