If you didn’t know any better, it would be easy to assume that Mazda’s continuing obsession with all things rotary is simply tilting at windmills. While other companies pour their hard-won R and D budgets into hybridization, electrification, and semi-autonomy, little Mazda keeps talking about a return for the hilariously named Wankel rotary engine. Why?

Fifty years ago this week, on May 30, 1967, Mazda released its first production rotary-powered machine, the Mazda Cosmo. Called the 110S in export form, it was a sleek, futuristic-looking sports car that set the stage for a coming flood of rotary-powered vehicles.

Yet only now, on its 50th birthday, is the Cosmo beginning to get the proper respect it deserves, both as a front-runner and as a design achievement in its own right.

As we celebrate the Cosmo’s birthday, it’s important to pull back the curtain on the development of the rotary engine, and just what it meant for Mazda. Just as Subaru owes its character to the flat-four engine and all-wheel drive, the rotary is the defining technology of Hiroshima-based Mazda. It doesn’t matter if it’ll take them another decade to figure out how to make a rotary fit modern emissions and efficiency requirements – the way it happened the first time changed Mazda forever.

The plow mare and the racehorse

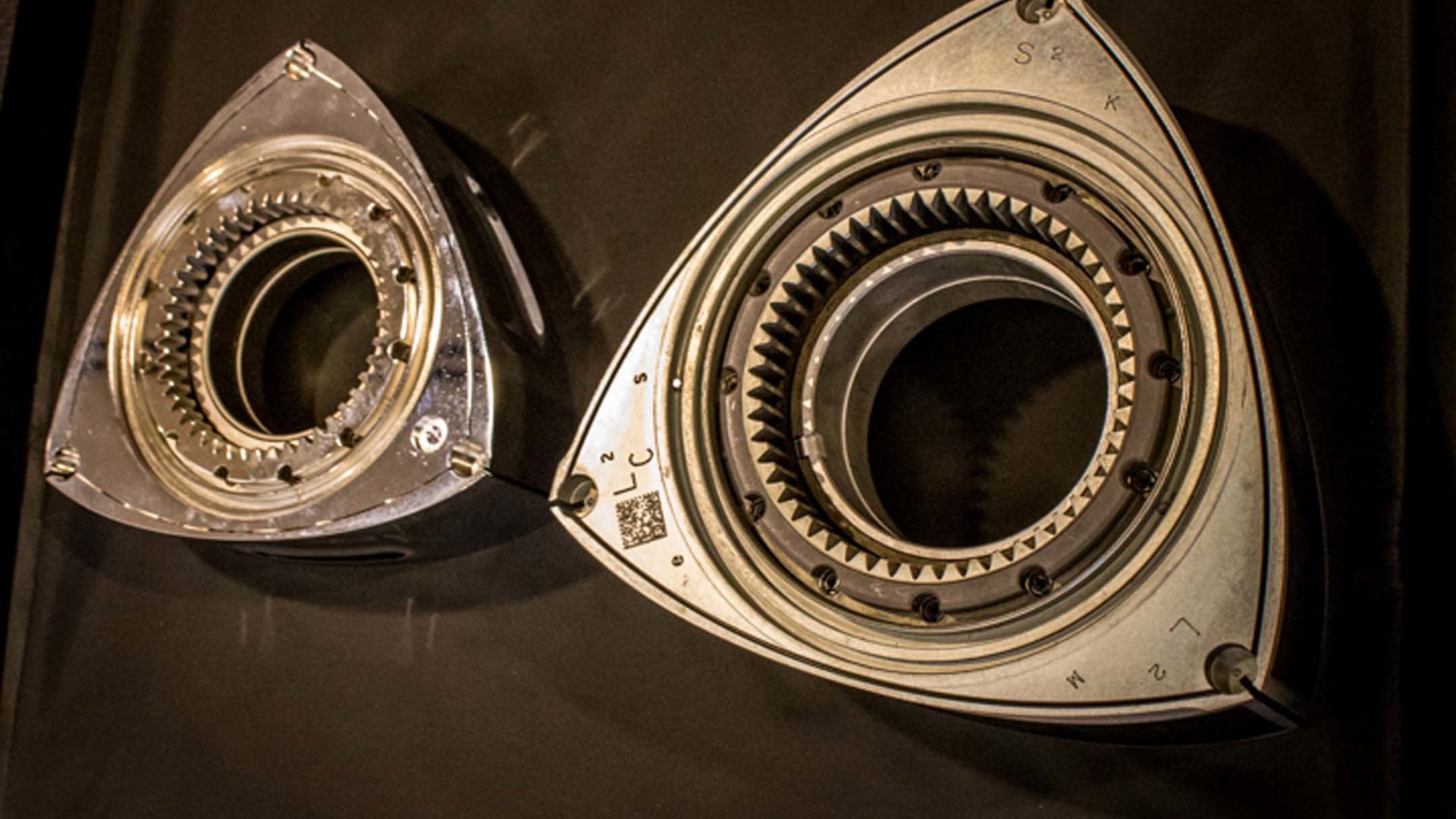

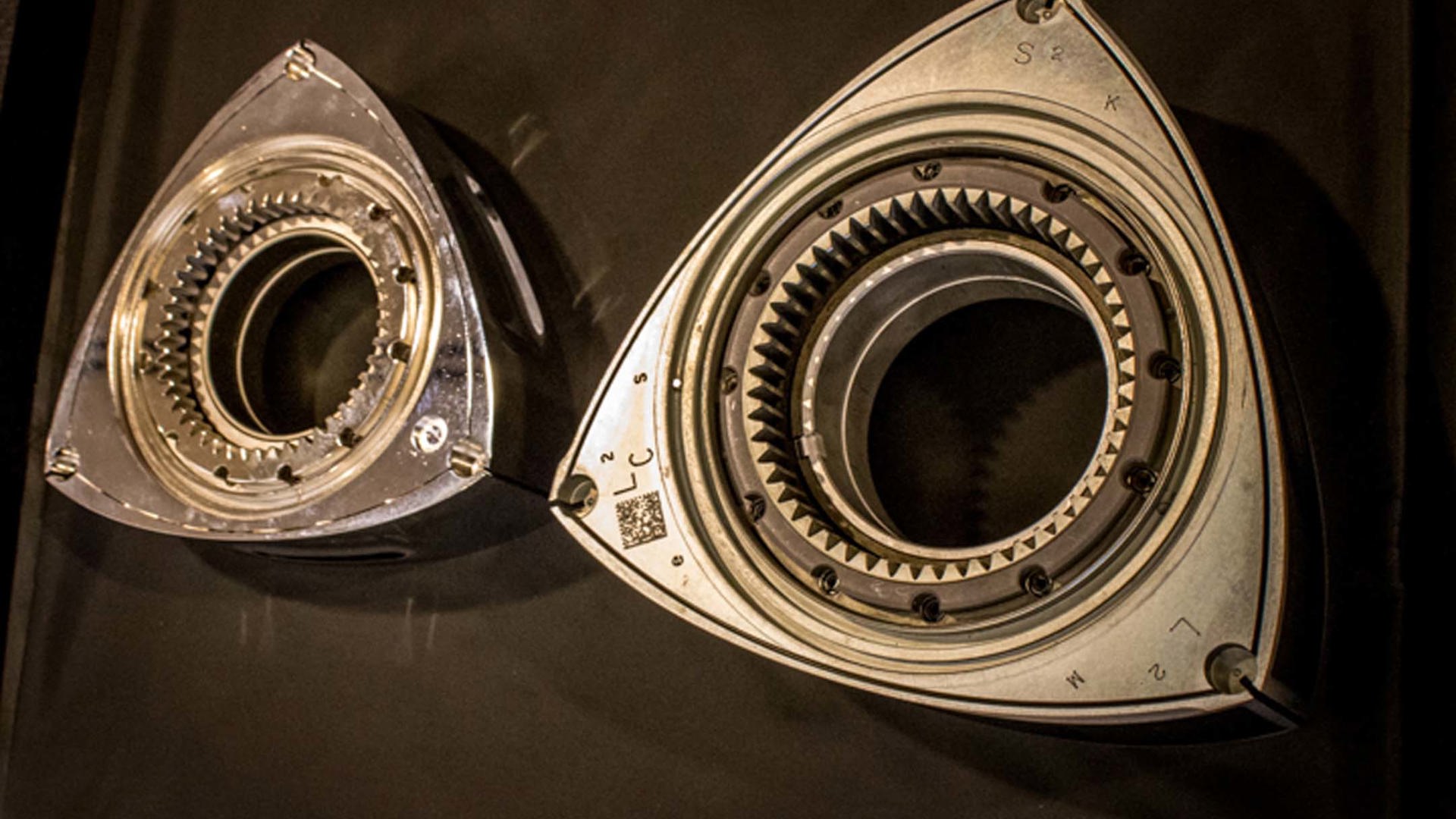

“Rotary engine” is a catch-all term that describes any one of several dozen engines that operate without pistons. Most are developmental or only theoretical in application, with the only two production varieties being a brilliant-but-complex spherical steam engine from the 19th century, and the internal combustion engine proposed by Felix Wankel.

Wankel’s design, first patented in 1929, was far more complex than the rotary most people are familiar with. In his original DKM prototype, developed with German manufacturer NSU, had both spinning rotors and a rotating housing. Beautifully balanced, it was also very complicated and required disassembly to service. The first running prototype was successfully fired up on February 1, 1957, making 21 hp. Perhaps that doesn’t sound all that impressive, but a few more details should help: the prototype engine displaced just 125 cc, and spun all the way to 17,000 rpm flawlessly. By 1958, it had completed a 100-hour stress test.

However, NSU knew Wankel’s design, while technically brilliant, wouldn’t be practical. Another engineer named Hanns Dieter Paschke developed a simpler layout with a fixed rotor housing – done without the knowledge or approval of Wankel. When the second prototype was shown, Wankel lamented, “You have turned my racehorse into a plow mare.”

Unlike a piston-powered engine, which operates much like a cyclist’s legs pumping away, a rotary engine transmits power directly to the crankshaft. All four cycles of intake, compression, ignition, and burn cause the unique three-sided rotor to spin around a peanut-shaped combustion chamber, turning the centrally mounted crankshaft.

The advantages of a rotary are volumetric efficiency, and a compact design. The main disadvantage, at least at first, was lethally poor long-term reliability.

The 47 Warriors

At the beginning of the 1960s, many manufacturers were interested in the rotary engine, as it seemed to provide a compelling combination of packaging efficiency and should theoretically be more reliable than a conventional piston engine, having fewer moving parts. American aircraft maker Curtiss-Wright entered into an agreement with NSU to develop the Wankel for aeronautical applications, and almost everyone applied for a license: Alfa-Romeo, Citroen, AMC, GM, Porsche, Suzuki, Rolls-Royce (!), and of course Mazda.

Suzuki produced the RE-5, a rotary-powered motorcycle, and NSU released first the wonderfully named Wankel Spider in 1964, and later the Ro80 sedan. Perhaps the most interesting non-Mazda application was in the C111 Mercedes-Benz concept car. In 1970, this golden, gull-winged wonder received a 350 hp, four-rotor engine that was good enough for a top speed approaching 300 km/h. A shame it never went into production.

However, one by one, manufacturers started shying away from the rotary. The problem? The tips of those rotors are subjected to terrific heat and force, causing them to wear out, or damage the housing. In the case of NSU, the damage was so bad, warranty issues killed the entire company. Despite driving quite well when it was running, the Ro80’s engine often wore out in a little over a year of driving. Eventually, the company was swallowed up by VW and became part of Audi.

But Mazda wasn’t about to give up. Alone among manufacturers, Mazda had more than just a technical interest in the rotary. Japan was focused on consolidating its growing automotive industry as much as possible, to strengthen and streamline brands. Nissan swallowed up Prince. Toyota ingested Hino.

Mazda was a much smaller company than the giants headquartered in Tokyo, and needed some unique technology to differentiate themselves and justify their existence. They pinned their hopes on the rotary engine, but they still needed to get it to work.

A team of forty-seven engineers were assigned to the task, headed up by Kenichi Yamamoto. Yamamoto gave the team the fire they needed, calling them the Shijyu-shichi Shi – the 47 Warriors. These legendary, ancient samurai fought with absolute focus to avenge their fallen master, and Mazda’s engineers sought this same single-mindedness.

But for a long time... it didn’t matter. The rotary refused to behave itself, setting off minor oscillations that caused chatter marks and wear on the housing and apex seals. The engineers tried all sorts of material, with little success.

Then one day – the breakthrough. By changing the shape of the seal at the tip of the rotor, Mazda’s engineers were successful in eliminating the harmonics causing the chattering. A new aluminium-carbon composite material helped with toughness, and the first rotary-powered Mazda was soon ready to run.

Cosmo’s entrance

Built around the space-savings offered by its two-rotor 10A engine, the Cosmo Sport was a far more interesting design than Japan’s first proper supercar, the Toyota 2000GT. Making 110 hp at 7,000 rpm and 96 lb-ft of torque, it wasn’t quite a straight-line menace, but rather a well-balanced sports coupe that loved to be revved.

Previewed in 1964, the Cosmo took a further three years until its official release, as Mazda carefully honed the car with input from their dealers. It launched to considerable acclaim, but remains very rare, as Mazda could only build a single car per day. A total of 1519 cars were handmade between 1967 and 1972, the bulk of them the later Series II versions.

The Series II was introduced a little more than a year after the first Cosmo, and came with boosted power, an increased wheelbase, bigger brakes, and a five-speed manual. Because of its rarity and importance, the Cosmo is just now beginning to command significant values at auction.

But never mind the collectability factor, the Cosmo is just plain cool. It might come as little surprise to find out that it even had a starring role as the transportation of choice for Ultraman, the campy 1960s Japanese kaiju-superhero series. There was a brief attempt at racing, with two lightly prepped cars attempting the ridiculously gruelling 84-hour Marathon de La Route at the Nürburgring. One car made it to the 82nd hour mark, the other finished fourth overall. Pretty convincing stuff.

Begin the Racing Beat

Having established a foothold for the rotary engine, and ensured their continued survival, Mazda began expanding their technology from halo car to mass production. The R100 brought rotary power to the Japanese masses, and they’d eventually even build a rotary-powered pickup, the REPU.

However, the rotary engine’s real triumph would come as a result of an unlikely partnership between a rangy Texan engineer and a short Japanese racer. They met over ice cream in the shadow of Anaheim’s Disneyland, and despite the language barrier and cultural differences, Takayuki Oku and Jim Mederer recognize something in each other.

In Hiroshima, Mazda released the RX-2. Technically merely a rotary trim level for the Capella sedan, it may be thought of as a rival to the Datsun 510. When it arrived in the US, its 12A rotary engine made around 95 hp or so. Then the Racing Beat crew got their hands on it.

Funded by Car and Driver, at the behest of editor Patrick Bedard, Racing Beat set about preparing the little RX-2 for a season of IMSA racing. While fettling a piston engine for racing practically came with a dog-eared recipe book, cracking the secrets of the rotary required mechanical genius.

Jim Mederer was that genius. He figured out how to port the engine – the so-called bridge-port, named for the metal bridge splitting the port to preserve corner seals – and squeezed some 218 hp out at 8,400 rpm. The way Oku tells it, they would run the engine in their garage in the evenings, and then shut it off before the cops came. You could hear it two or three miles away.

The RX-2 started winning races immediately, giving Mazda a much-needed boost in credibility. With Racing Beat parts soon in demand from club racers all around North America, the later RX-3 and RX-4 started rubbing fenders at every local track. The fans were passionate, committed, and successful. Sure, a rotary wasn’t an obvious choice, but sometimes it was almost an unfair advantage.

Prescription for performance: RX-7

Up to this point, we’ve been talking about cars that even many rotary-engine enthusiasts have never heard of. While the early cars enjoyed their successes, Mazda’s real game-changer showed up in 1978. The RX-7 was fast, sleek and competitive. It would become a legend.

Hear me now: these first-generation cars are currently deeply undervalued. They are easily the equal of an early Datsun 240Z in performance, and if fitted with period-correct modifications will likely run rings around the competition. You’d pay more for a decent Miata than you would for a pristine GSL-SE, with its fuel-injected 13b engine.

The second-generation car is even tastier, particularly the hard-to-find Turbo II model. Turbocharging and rotary engines work well together, assuming the owner is careful about maintenance. The second-generation car is not without its quibbles, but makes a compelling alternative to a contemporary Porsche 944.

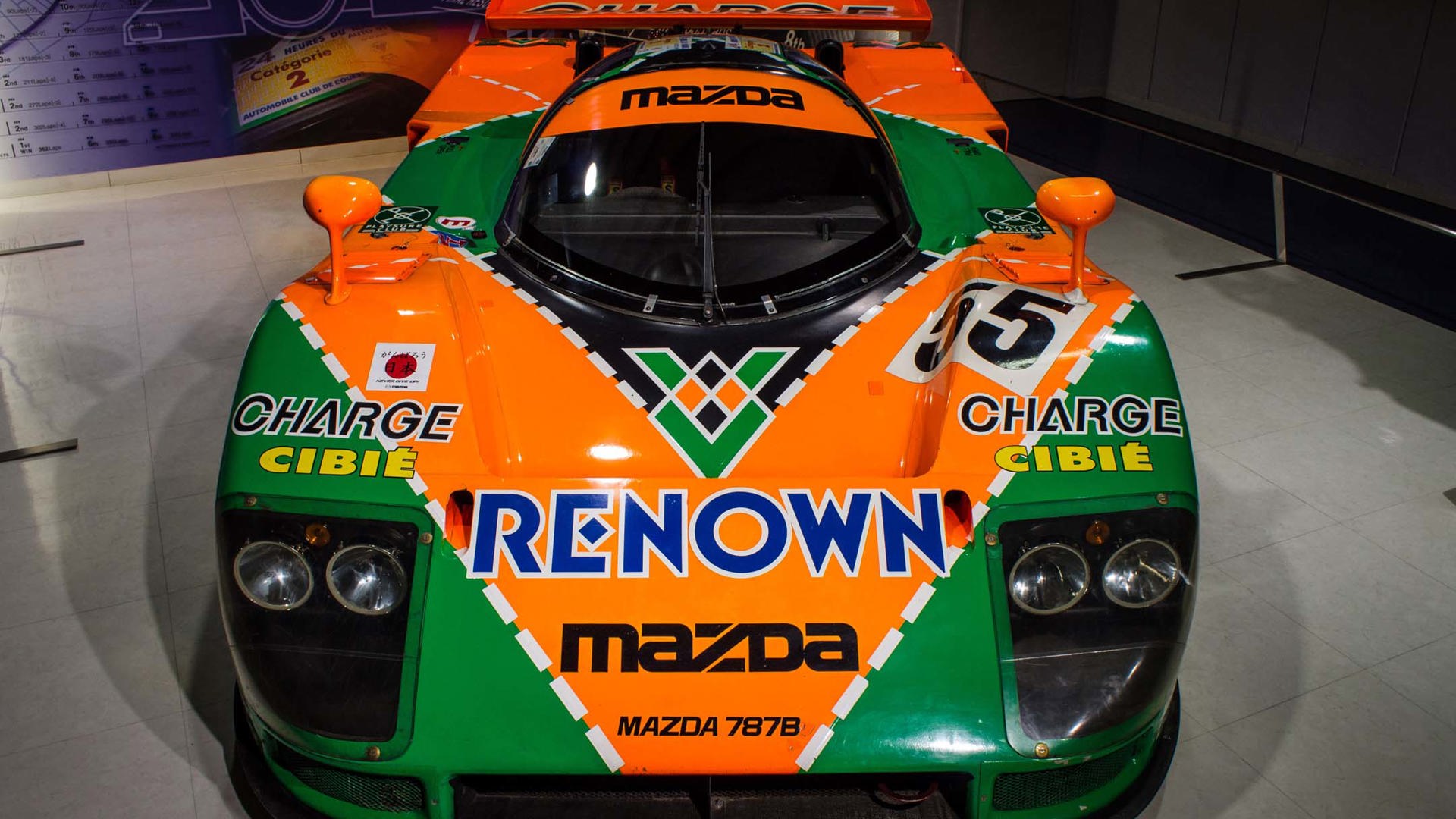

And then there’s the ship that’s already sailed: the FD-chassis twin-turbo RX-7. A reputation for unreliability sunk values quite low just a few years ago, but now the buying public is beginning to realize that these cars were the end of an era. The FD was launched just as Mazda was celebrating its 1991 win at the 24 hours of Le Mans, and the company threw all kinds of technology at the project. A sequential twin-turbo 13b required keeping an eye on the temperature gauge (and not skimping on premium fuel), but the car itself was delightfully balanced to drive. It was at once highly complex and utterly pure.

It was also really expensive, and sales suffered. Mazda also nearly had an Ro80 moment here, as engine failures were frequent, thanks in part to owners who weren’t perhaps as fastidious about maintenance as they should have been.

Production for North America ended at the tail end of 1995, with the last RX-7 delivered in 1996. The Mazda RX-8 would succeed the RX-7 as the flag-bearer for the rotary, but it wasn’t nearly as hard-edged as the RX-7, and it too finally succumbed.

An uncertain future

Some time ago, by dint of annoying the right people until they rolled up the garage doors, I had the chance to drive one of the rarest rotary-powered machines ever made. Built as a gift for Mazda USA senior VP Robert Davies, who regularly races a four-rotor 787B in historic events, it’s a 2002 RX-7 built to Japanese domestic-spec as a Spirit R. Very few of these were made in right-hand drive, and only one was ever made with the steering wheel on the left.

Mazda lent the car to me for a day, with a brief note about it being historic and irreplaceable and all the rest. I resolved to drive it carefully, and take lots of nice pictures. That lasted about four kilometres.

The Spirit R, like the 47 Rōnin, like the frontiersmen at Racing Beat, like the team at Le Mans, was infused with something Mazda calls their Challenger Spirit. It’s not necessarily an underdog thing, more a refusal to quit until breakthrough is achieved.

On that day in the sunny California canyons, the faster I went, the better the Spirit R like it. We chased down sport bikes, screamed up through the S-bends, hurtled towards redline on a surging wave of boosted air and fuel. Things were, it has to be said, not particularly efficient.

Some time later, I had the chance to drive an electric Demio with a tiny rotary installed as a range-extender. The Demio was sold as the Mazda2 over here, and it was decidedly odd to hear it warble a rotary song as the battery depleted.

In one sense, perhaps that’s the future for the rotary. Look at what Acura’s been able to do, blending hybrid and turbo technology together with the NSX. It’s not as pure as the original, but it moves the story forward.

But on the other hand, Mazda might be trying to solve the knotty problem of making a rotary run clean for many years yet. No one else is attempting the same feat, so it’s a burden to be shouldered by a single company.

To the uninformed eye, Mazda’s just tilting at windmills. Rotary technology is a dead-end, at best an interesting footnote to the last chapters of the combustion engine.

But I have heard the scream of the Le Mans winning 787B hurtling around the track, have felt the switch-over as the big turbo kicks on at 4,500 rpm in an RX-7, have experienced the creamy-smooth turbine thrust of a Renesis engine and the odd warble of a tiny rotor augmenting an electric drive.

The rotary engine is Mazda. Mazda is the rotary engine. The obsession might not make sense to a casual observer, disinterested consumer, or the accounting department, but the truth is there. Mazda isn’t trying to resurrect a lost technology. Instead, they’re just listening to the beat of their three-chambered heart.