In his 1940 novel You Can’t Go Home Again, Thomas Wolfe wrote, “Things which once seemed everlasting … are changing all the time.” The reason you can never go home, he mused, is because “Few automobiles are vast enough to hold the sound of time.”

Actually, that’s not quite true: First off, Wolfe said “buildings” not “automobiles”. And secondly, some cars are indeed vast enough – in character, if not size – to hold at least a clear echo of the sound of time.

Sitting at an outdoor table in one of the coffee shops along Vancouver’s bustling Broadway Avenue, my mind is noisy with time’s echoes as I admire the bright orange gumdrop of a car parked a few feet away. I’m not the only one it seems, because pedestrians of every age rubberneck as they pass by, pulling out cellphones to take photos of the Inka-painted 1973 BMW 2002tii I’ve been given the privilege to drive this day.

For me the car serves up some very particular memories, because I was lucky enough to buy my first 1972 BMW 2002 when I was a newly minted 16-year-old driver. That 2002 belonged to my first boss, who managed a community centre where I did set-up and clean-up work. The car was 10 years old at the time, and while these days a 10-year-old BMW could qualify for certified pre-owned sales status, back then it translated into semi-beater status: The little BMW had a blown clutch slave cylinder (my boss started it in gear and shifted no-clutch), a busted window regulator (she tore out the interior door panel and jammed in a broken hockey stick to hold up the window) and, prompting the sale, it had ignition points so long-neglected that they’d welded shut, rendering the engine inert. For the princely sum of $325, plus a set of points and a bottle of brake fluid, I began a 15-year relationship with the BMW 2002, and a now-35-year relationship with the marque.

A boxy marvel

The 02 Series (a designation reflecting its two-door body style) was the car that saved BMW, catapulting the company from European semi-obscurity into North American and international consciousness.

It was based on a shortened version of the Neue Klasse (New Class) four-door sedan, which was itself developed in effort to move BMW from low-volume sports and luxury vehicles into the more profitable mainstream.

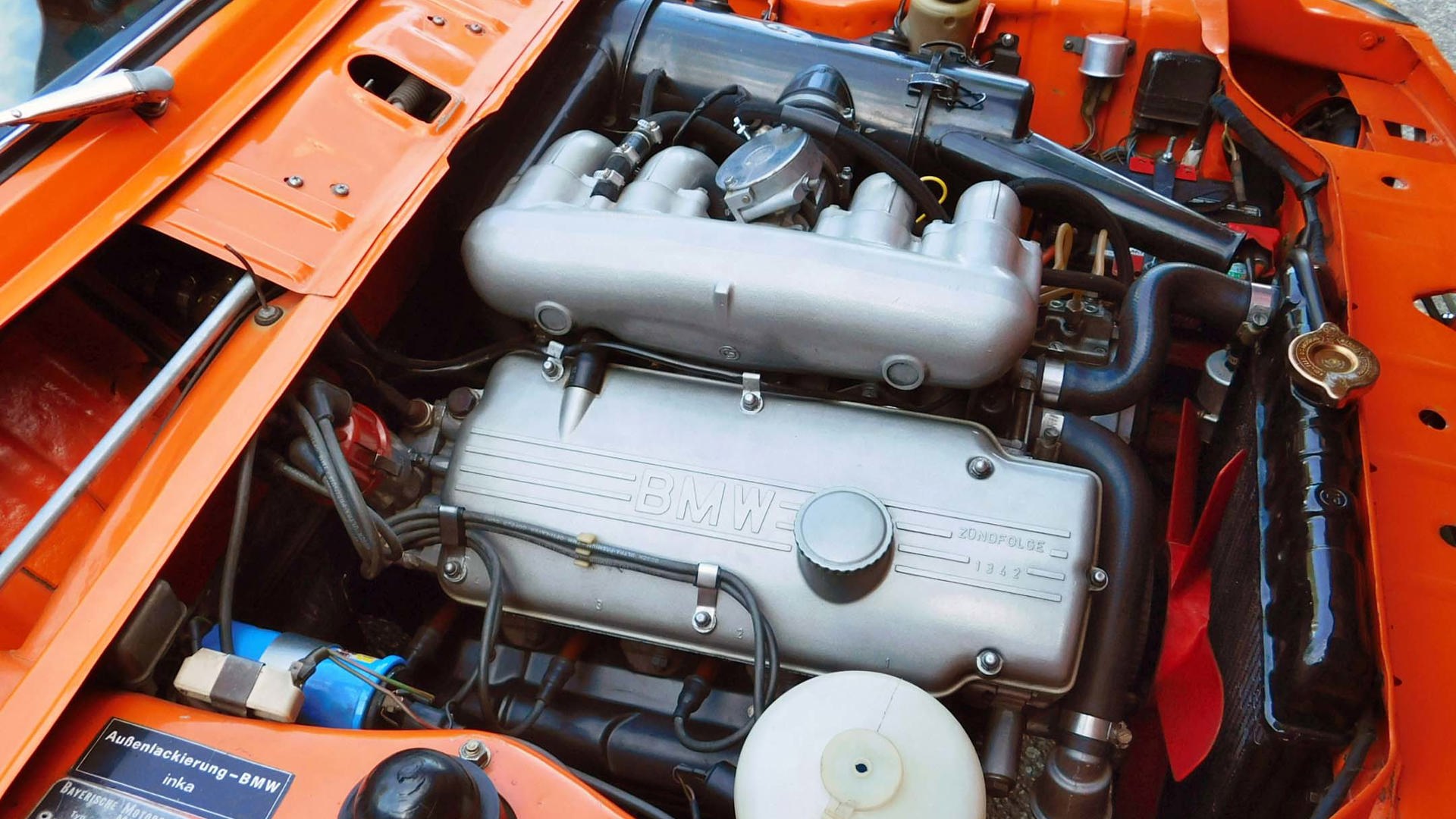

Introduced in 1966 as the 1600-2 (and later renamed 1602), the 02 was initially fitted with a 1.6L four-cylinder engine developing 84 hp. Then, in a move that would surprise exactly nobody, Helmut Werner Bönsch (BMW’s director of product planning) and Alex von Falkenhausen (designer of the Neue Klasse’s M10 engine) each independently modified their personal 1602s by putting in the bigger 2.0L, 113 hp engine from the 2000 four-door sedan. When US Importer Max Hoffmann wanted a sportier version of the 1602 for the North American market, the two BMW executives put together a proposal based on their modified cars, and the 2002 was officially born for the 1968 model year.

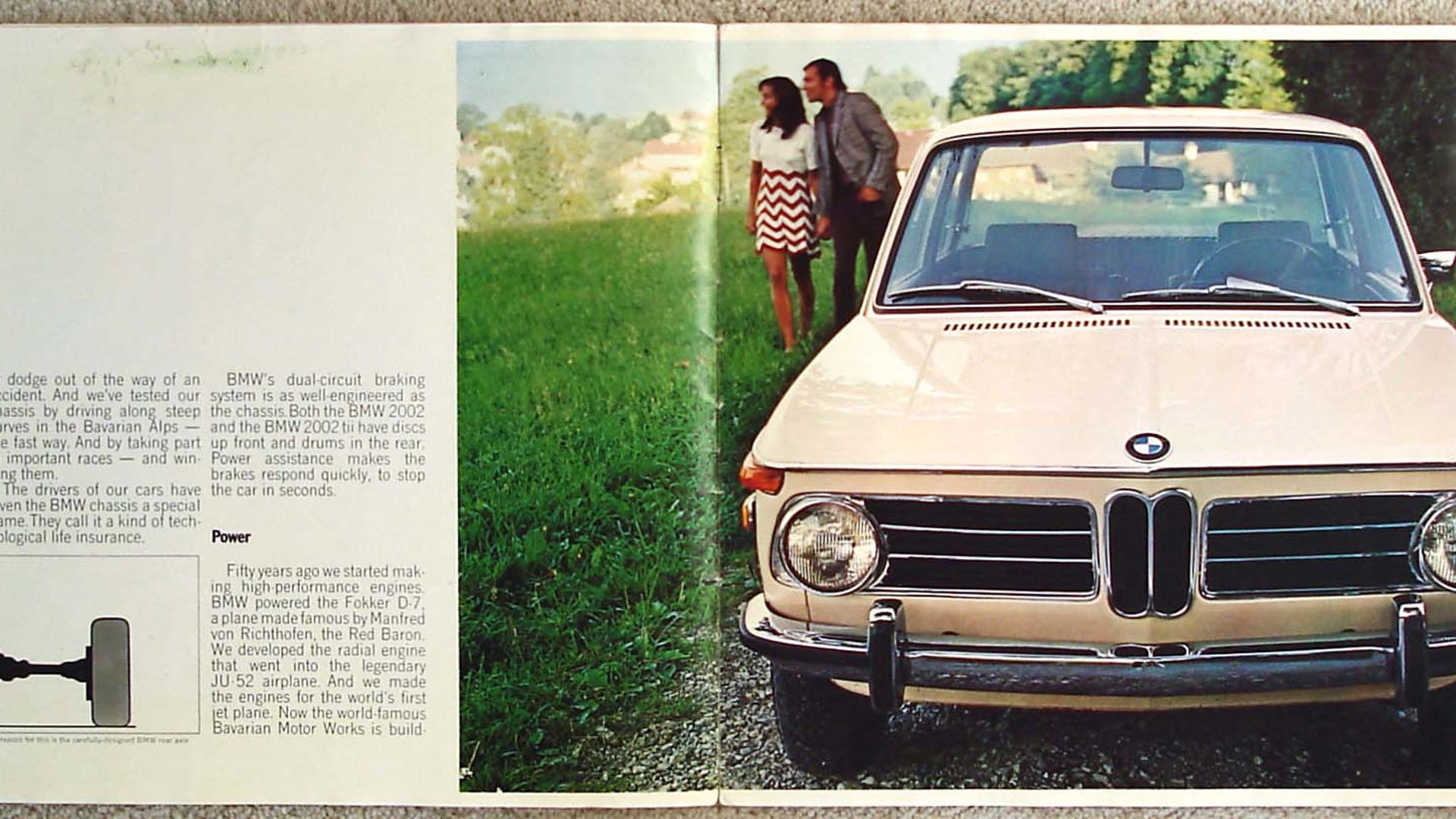

Dubbed the “Whispering Bomb” by the German press, it was a boxy marvel, a practical and unobtrusive-looking little two-door sedan with performance and handling that rivalled the best sports cars of the day. Writing about it in an unabashedly gushing review in Car & Driver, editor David E. Davis famously said “turn your hymnals to Number 2002 and we’ll sing two choruses of Whispering Bomb.”

(A quick note here about the 2002’s unobtrusive styling: the Neue Klasse sedans were penned by Wilhelm Hofmeister, who gave them the original Hofmeister kink at the bottom of the C-pillar. The design for the two-door version was done by Giovanni Michelotti, who also penned the Triumph Spitfire.)

A trip though time

The Inka orange 1973 2002tii belonging to Paul Winterton is an immaculately preserved, unrestored original car in remarkably good condition, and – except for its Momo wood steering wheel and Mini-lite style alloy wheels – almost entirely unmodified . There’s a certain irony in this, given that the 2002 was born as a modified 1602 and most owners were quick to alter and accessorize their cars in all sorts of ways.

My best and longest-serving 2002 was a quite different machine than left the factory, with bigger wheels and tires, Bilstein gas shocks, high-compression pistons, a mildly re-ground cam, a TI distributor, a Weber 32/36 carburetor, an Ansa exhaust system, an oil cooler, a Ford Pinto radiator (the accepted bolt-in hack to solve overheating issues), seats from a more modern BMW, a Kamei air dam and a non-factory metallic blue paint job.

On the road, my car had a loud, raspy exhaust note and plenty of induction noise from its Weber carburetor. It had a stiffer suspension than the stock car, with flatter handling. And thanks to its modified engine, I suspect it was at least as powerful as the fuel-injected tii.

The essential character of the 2002, however, is such that it shined clearly through all these modifications. And so Paul’s 1973 2002tii feels completely familiar, despite the fact that in this case, time has changed almost nothing.

The tii’s drivetrain is quieter than my car’s, for sure, with a smoothly whirring mechanical song that drowns out most of the exhaust and induction noise. The controls – especially the signal and high-beam stalks, gear lever and park brake handle – are all longer and more slender than I recall, a real contrast with the fat, stubby controls popular in modern cars. The 1973 and earlier BMWs also had a quirk, in that the signal lever was on the right-hand side of the steering column, not the left. It takes a few miscues before I adapt back.

The suspension remains a marvel, a reminder of why the 2002 was such a revelation in its day. In stock form it’s softer and more compliant than you’d expect in a modern sport sedan, with more suspension travel. Combined with the 2002’s comparatively tall tires, this gives a far more comfortable ride than we often accept today. It also means the 2002 leans more in the corners – a modern BMW 135i feels like a race car by comparison. But that doesn’t mean the 2002 doesn’t handle: it has great balance, perfectly communicative steering (no power steering getting in the way here) and tenacious grip. At least, up to a point.

Modern BMWs use a multi-link rear suspension, but the 2002 used semi-trailing arms that provided famously good handling up to the limit, and notoriously sudden oversteer once you crossed that threshold (this was due to the changing suspension geometry as the car leaned). Once you knew what you were doing it was good fun, but if you didn’t know what you were doing it could bite you badly. Driving Paul’s tii, part of me simply can’t believe that I used to sling these cars sideways for the sheer joy of it, but part of me wants to drop the car into second gear and power-slide around a corner. Mind you, I imagine Paul would cut my drive abruptly short if I tried such a thing.

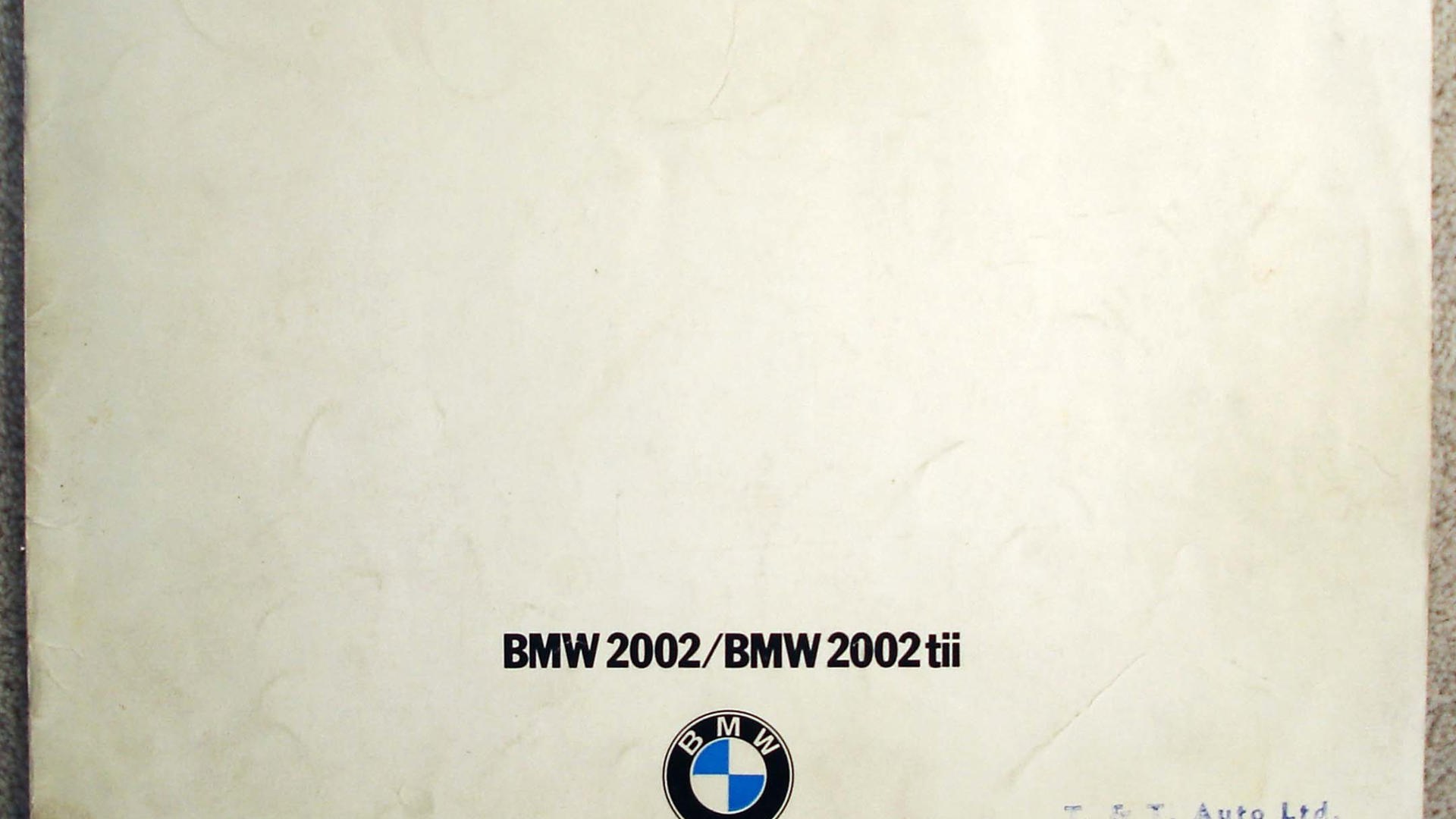

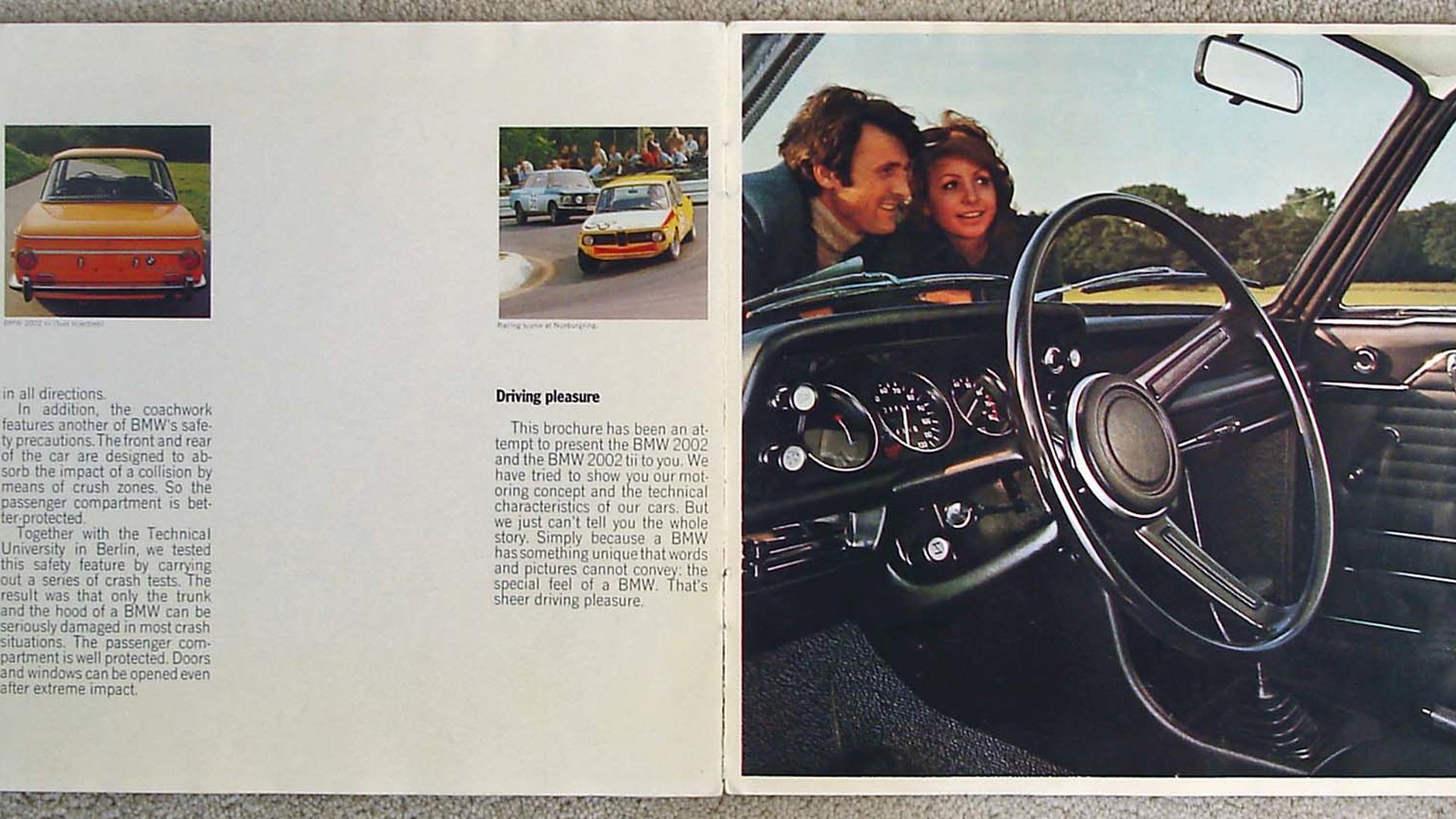

Acceleration could be described more as “enthusiastic” than outright fast. The official BMW brochure Paul still has from T&T BMW in Calgary (where the car was originally sold) claims a 0–60 mph time of 12.8 seconds for the 113 hp 2002 and 9.9 seconds for the 140 hp, fuel-injected 2002tii, but a long-ago salesman crossed out those numbers and changed them to 9.8 for the 2002 and 8.8 for the 2002tii. Classic car sites suggest 9.7 seconds for the tii, and my own modified 2002 made the run in just under 10 seconds, so I reckon the salesman was a bit optimistic. At any rate, the engine has a wide sweet spot, making it a joy to wind through the gears.

Paul’s car has a rebuilt transmission that’s a touch slower and heavier going into second gear than I recall from my own cars. The alternative (which many 2002 owners will remember) is a quick, light, but noisy second-gear shift action thanks to fast-wearing synchromesh. In 1972 BMW switched from smooth but delicate Porsche synchromesh to notchier but more robust Borg-Warner synchromesh. I remember installing three different transmissions when I rebuilt my last car, until I found a low-mileage one in perfect condition.

Inside, the 2002 is finished to a standard that was considered quite luxurious at the time, and still looks good today, if perhaps a little Spartan (the padded rear ashtrays are an extravagant exception). Paul’s car has a crack in the dash emanating from the instrument binnacle, something that I remember from every 2002 I ever owned. He’s replaced the steering wheel with a wood-rimmed Momo wheel, and installed period-correct coco mats, but other than that it’s bone stock. Thanks to the upright greenhouse, the big sunroof (a $225 option in 1973) sits straight overhead instead of somewhat behind you as sunroofs in modern cars do. All in all, it lends the 2002 an open, airy feeling and outstanding outward visibility that I miss to this day.

Mind you, if you were stuck in traffic on a hot day things didn’t feel so airy, because there were no dash vents and you sat on vinyl seats. If you were moving at any sort of speed the wing vent windows could pour vast quantities of air over you, but if you were stopped, you sweltered. The lack of dash vents did allow a big dashboard shelf however (another feature I miss to this day), and the trunk is enormous.

The classic conundrum

Parked at the coffee shop, Paul and I watch passersby gawk at the tii as we talk about the realities of owning a nearly 45-year-old car. Thanks to the 2002’s inherent practicality – something that kept me in the 2002 fold rather than buying a much-desired Triumph Spitfire – Paul still uses his car as a daily driver, provided there’s no rain predicted or moisture on the ground. In his garage he has dehumidifiers to further keep moisture away, as the 2002 was built in the days before factory galvanization and rust is always a concern.

Ultimately, that’s why I’m not sure I can ever go home again. A good 2002 these days is worth at least $30,000, and you become as much a caretaker as an owner. So despite the car whispering “Thrash me!” in your ear (and they really do), it would seem like sacrilege to be thrashing on it, loading it to the brim with friends and skis to drive to the mountains, and generally using it up. It’s a bit of a conundrum, because that’s what these cars were built for.

Mind you, Paul argues that most of the wearable bits are still available, so there’s nothing stopping you from driving a 2002 like it was intended, provided you take care to keep the rust at bay. He’ll be driving his car to Monterey, California, for Vintage Week this summer, taking the twisty Pacific Coast Highway route – and he won’t be babying it along.