I have a dream job. I’ve heard it a million times; I don’t deny it. After more than 13 years covering the auto industry, I’ve travelled the world, driving some of the most beautiful vehicles and roads in the name of “work”, including the Stelvio Pass in the northern Italian Alps in an all-new Alfa Romeo Stelvio; California’s famous 17-mile scenic drive along the Pacific Coast in a Lamborghini Gallardo Spyder; and Alaska’s Top of the World Highway in an RV. But sometimes it’s not about the drive, but the destination.

Today, a massive limestone monument on Vimy Ridge stands as a memorial to loss and sacrifice, paying tribute to all Canadians who served during the bloody four-year conflict.

At least, that’s the case with my latest adventure. Truth be told – it’s a bucket list trip. A drive to visit the Canadian National Vimy Memorial in Vimy Ridge, France – an iconic symbol of remembrance and tribute to all Canadians who served during the First World War. The timing couldn’t be better. 2017 marks Canada’s 150th birthday and the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Vimy Ridge during WWI, April 9–12, 1917.

The Battle of Vimy Ridge is Canada’s most prominent military victory. An extraordinary military feat, many historians consider it a defining moment in the growth of Canada as an independent nation. Fighting under the British Empire, soldiers from four divisions of the Canadian Corps fought together for the first time, attacking Vimy Ridge on Easter Monday, April 9, 1917. Where previous Allied assaults had failed, Canadians succeeded and captured it from German hands.

But the victory came at a huge cost. Of the nearly 100,000 Canadians who served there, 3,598 were killed and 10,602 were injured. By the end of the war, more than 650,000 Canadian men and women had served in WWI; more than 66,000 lost their lives and over 170,000 were injured. Today, a massive limestone monument on Vimy Ridge stands as a memorial to loss and sacrifice, paying tribute to all Canadians who served during the bloody four-year conflict.

Our route begins in Paris, France, driving a European-spec’ed 2017 Jeep Grand Cherokee Trailhawk 4x4 SUV powered by a 3.0L V6 diesel engine – one of four vehicles up for grabs for the drive to Vimy. It’s an ideal vehicle to take, considering Jeep’s deep military roots. 2016 marked Jeep’s 75th anniversary. Today, their vehicles are sold in 160 markets globally with more than 18 million produced since the brand’s birth in 1941 during WWII.

We travel about 175 kilometres north to Vimy Ridge. It doesn’t take long to get there since I’m driving at 130 km/h – the posted speed limit on the highway (110 km/h when it rains). As we near the exit to Vimy Ridge, it’s clear how significant Canada’s role was in WWI. One cemetery after another lines our route, commemorating not just Canadians but other fallen soldiers from France, Australia, and Britain. Gravestones appear in every direction. More than 7,000 fallen Canadians are buried in 30 war cemeteries within a 20 kilometre radius of Vimy.

A beautiful winding road flanked by maple trees line the entrance to the Vimy Memorial. The land where this massive limestone memorial sits and the surrounding 250 acres were gifted to Canada by France in 1922 for the sacrifices made by Canadians. The rolling hills, lush green country fields, and towering trees look breathtaking, but beneath the land lies the secrets and terror of war 100 years ago.

In the distance, the Canadian National Vimy Memorial emerges on the horizon. Impossible to miss, it’s magnificent. The memorial stands atop Hill 145, the highest point of Vimy Ridge, overlooking the Douai Plain, about 10 km north of Arras. Designed by Canadian Walter Seymour Allward, a sculptor and architect, it cost $1.5 million and took 11 years to build before it was unveiled by King Edward VIII on July 26, 1936.

Twin white pylons soar to the sky 27 metres above the base of the monument. Each pillar represents Canada and France – two nations plagued by war, but united in the global fight for peace and freedom. One tower bears the iconic maple leaf of Canada; the other the fleur-de-lis of France. The monument rests on 11,000 tonnes of concrete, strengthened by hundreds of tonnes of steel. The pylons and 20 haunting sculptures contain almost 6,000 tonnes of limestone, which came from an abandoned Roman quarry on the Adriatic Sea.

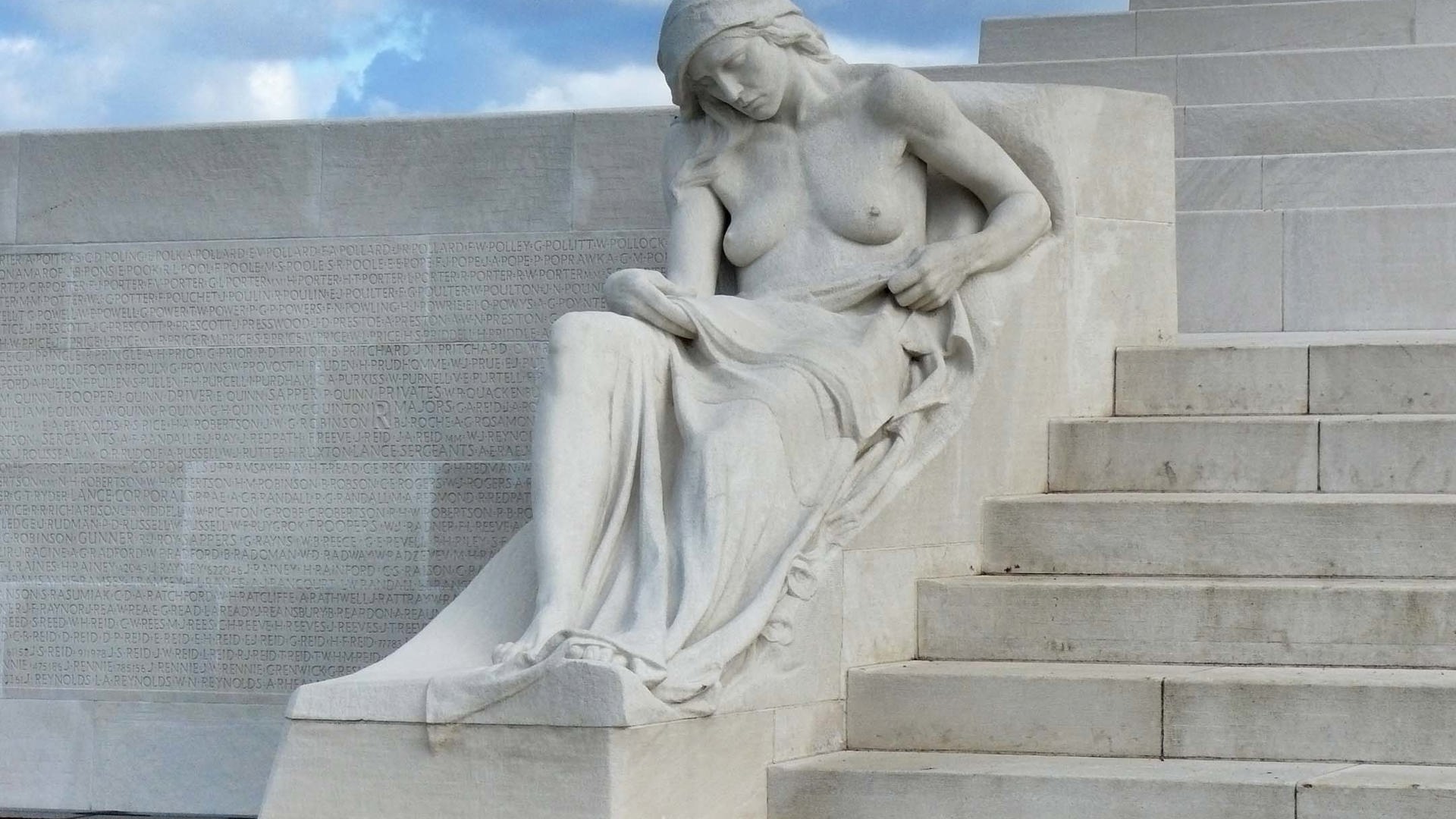

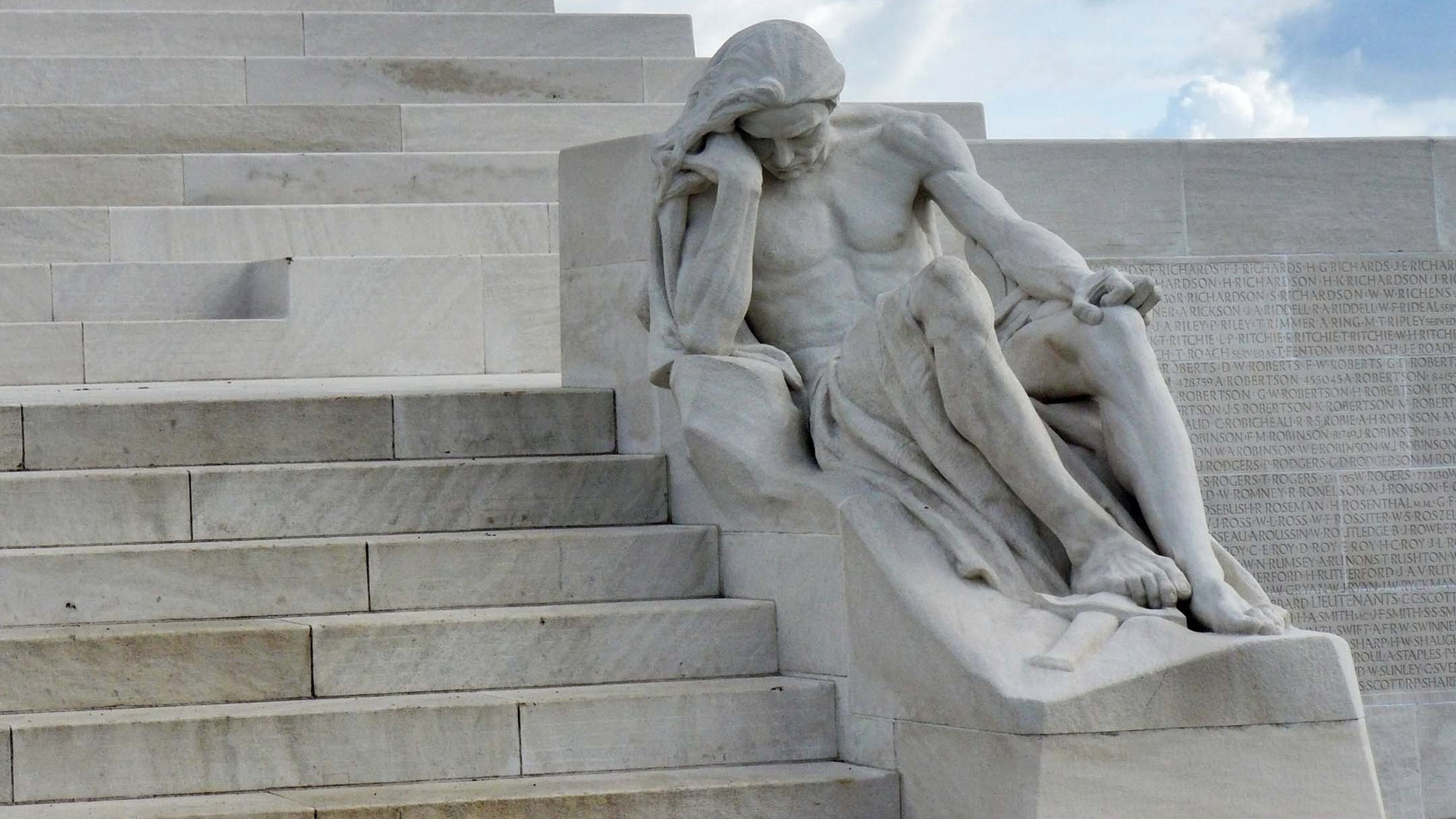

Walking towards the wide stone terrace, two figures dubbed the Female and Male Mourner greet onlookers, reflecting the mood of sorrow and loss. The statues were carved where they currently stand. One of the most powerful and moving figures is a woman, cloaked and hooded, her eyes cast down in grief. Carved from a single 30-tonne block of stone, she symbolizes Canada – a young nation mourning her dead.

Overlooking the rolling hills of Northern France, it’s quiet and peaceful – a stark contrast from the reality of war. Giant craters cover the grounds, reminders of the heavy artillery fire and underground mine explosions that blasted the surroundings. In the distance, a herd of sheep graze on the hillside. Most of the grounds are off-limits to the public – buried and unexploded munitions still litter the former battlefield, making it too dangerous for people to walk. Instead of mowing the grass, sheep graze on the land to keep the grass trimmed.

Below the female figure of Canada Bereft is the empty tomb, draped in laurel and olive branches, symbols of Peace and Victory. At the highest point of the pylons, figures representing Peace and Justice, rise approximately 110 metres above the Douai Plain. Below them are the figures of Truth and Knowledge as well as statues of Charity, Hope, Faith, and Honour. Around the figures are the shield of Canada, Britain, and France. Every statue is a masterpiece – perfectly scaled and carved, as beautiful to behold as Michelangelo’s David or Pietà. Inscribed on the walls of the monument are the names of 11,285 Canadians killed in France during the war who have no known graves.

A nearby visitor’s centre and museum provide additional background on Vimy. You can explore an extensive system of front-line trenches, underground tunnels, and dugouts – dubbed “subways”. The tunnels connected the Allied reserve lines to the front lines and allowed soldiers to move to the front quickly without being spotted by the enemy. A walking tour of a portion of the underground Grange subway, originally about 1,230 metres in length, is chilling. About two metres high and one metre wide, the subway was dug seven to ten metres below the surface to protect against heavy artillery fire. Our tour guide, a Canadian student and recent grad from the University of Toronto turns off the lights – the sheer darkness, damp quarters, and muddy grounds, a shocking reality of what the young soldiers faced on the front lines.

The visit is emotionally draining. After several hours, I return to my Jeep for the drive to Paris. This time, the road is filled with intermittent spurts of heavy pouring rain and bursts of sunshine – capturing my mood perfectly. Sure, I have crossed another item off my bucket list, but I can’t help wonder, what have we learned from our mistakes? What have we learned from the atrocities of war? Anything? War still rages in many parts of the world; the threat of nuclear war looms daily between the US and North Korea.

If you believe, as I do, that we have a duty as Canadians to honour and remember them so we don’t repeat the mistakes of our past, you should add the Canadian National Vimy Memorial to your bucket list. Trust me, you won’t be disappointed.

It’s worth the drive to Vimy.