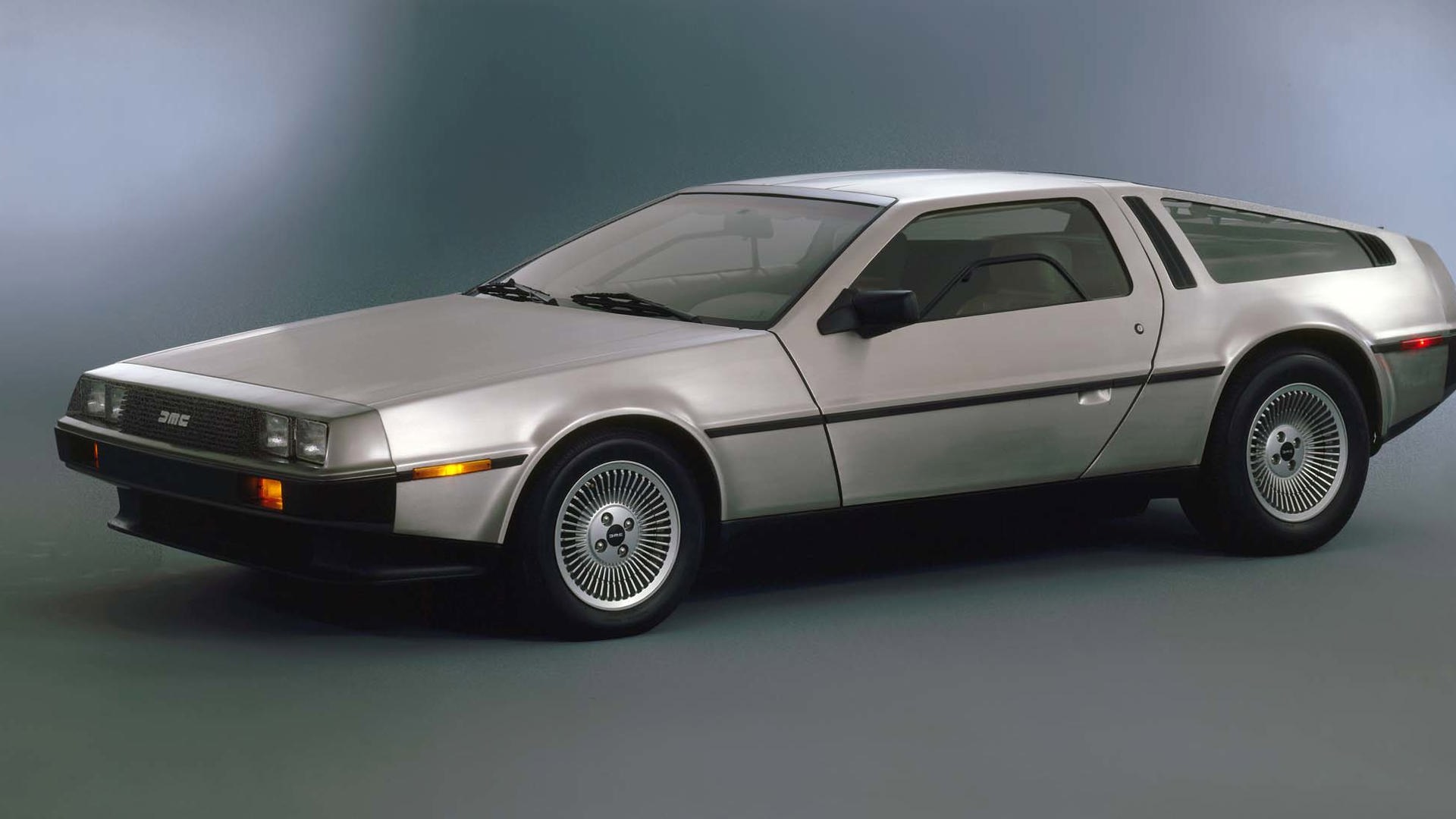

Possibly best known as the time-travelling machine in the 1985 movie Back to the Future, the stainless-steel DeLorean sports car is still popular with collectors. It could also appeal to new-vehicle buyers, since there are plans to produce a new replica model – but a piece of paper at the US government level currently prevents it from going ahead.

It’s a simple form to approve manufacturers for low-volume production under legislation that’s already been passed. It’s holding back other replica cars too, as well as the possibility of selling Britain’s iconic Morgan in the United States. It must be issued by NHTSA, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, and that’s where it’s stalled.

“In specific terms, we have a problem with NHTSA not having a boss,” says James Espey, vice-president of the DeLorean Motor Company (DMC) in Houston, Texas. “The law says NHTSA has to create a form (for low-volume companies), just like they would for any manufacturer.

“When Trump got elected, the director of NHTSA appointed by Obama resigned.” It’s unlikely the forms will be issued until the safety branch has a director, and while the current government has made a nomination, it hasn’t been confirmed.

The current DMC is a very successful and long-established DeLorean restoration business with locations in Houston, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Orlando, but doesn’t know when it will be able to put its all-new replica car into production.

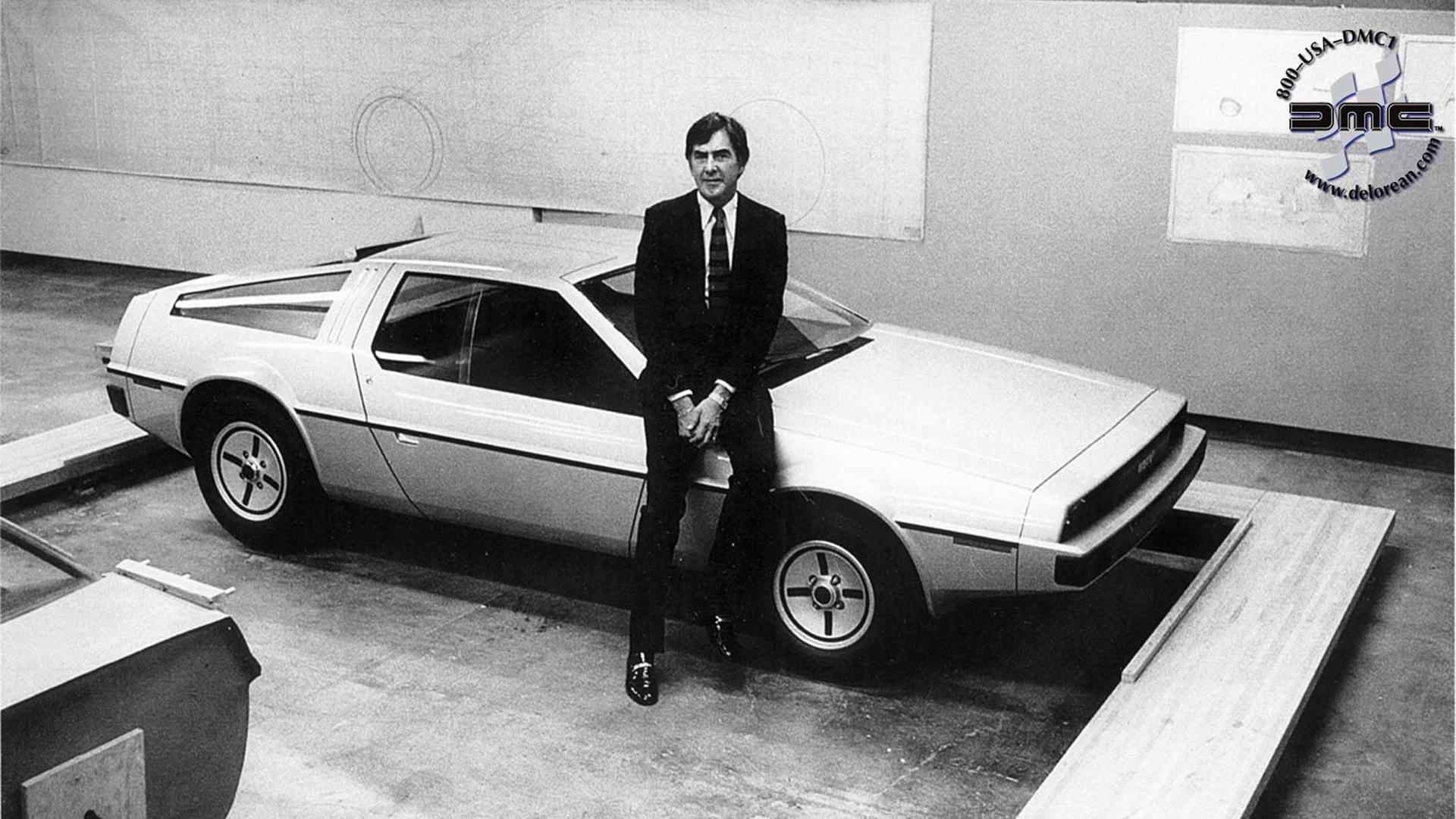

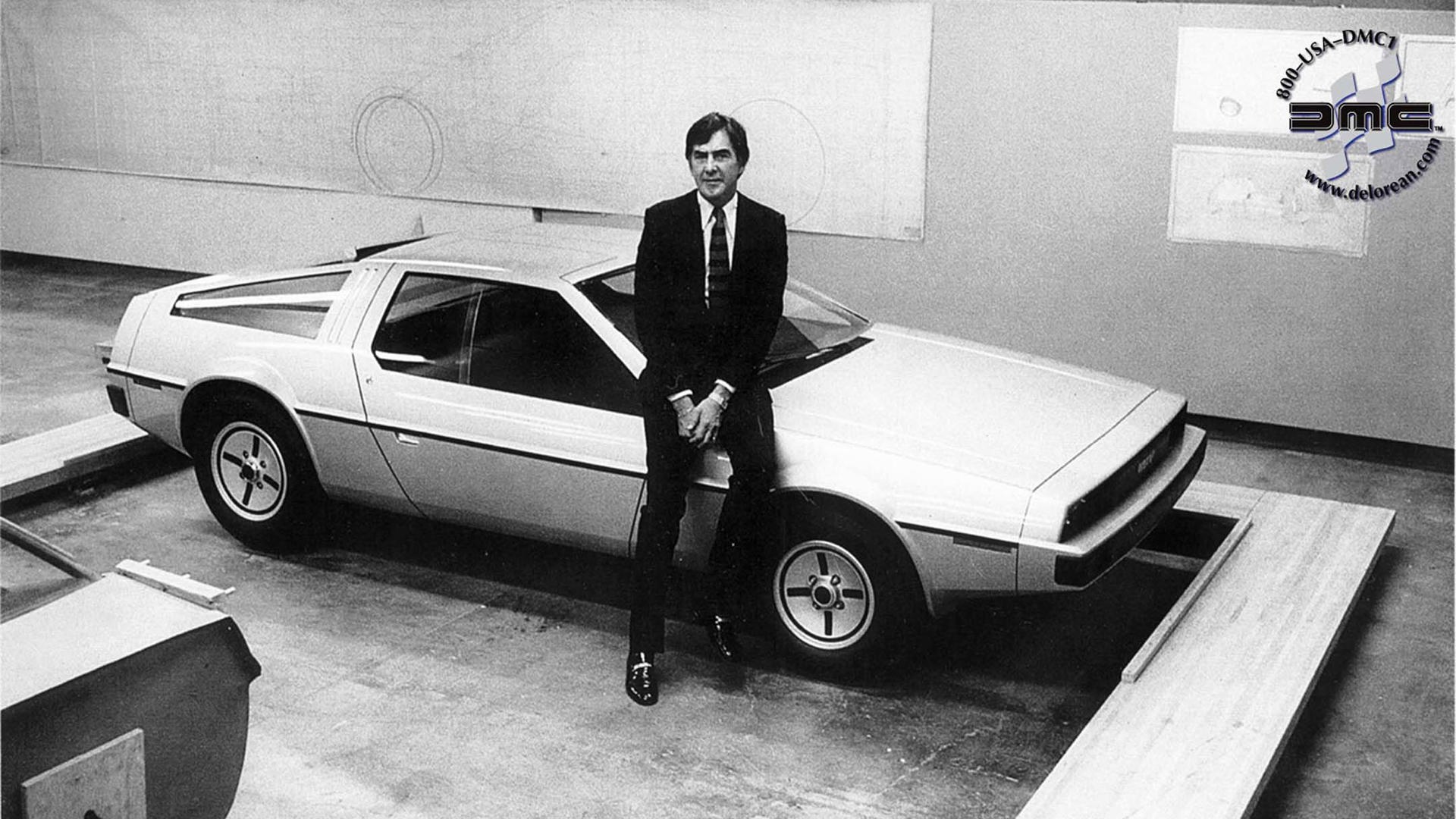

The original DeLorean is one of those classic “what might have been” stories. John DeLorean was the chief engineer at Pontiac when, in 1964, he had his team take the compact Tempest – which topped out with a 280 horsepower V8 – and add a 389 cubic-inch (6.3L) V8 making 348 horsepower. GM had a policy that restricted power based on the car’s weight, and DeLorean’s project exceeded it. But because management only looked at the models, DeLorean buried the engine in the options list as the GTO package, and quietly told key dealers how to order it. So many were sold that GM dropped its rule, and the Pontiac GTO became a model all its own.

DeLorean later moved to Chevrolet, where it looked like he might become the company’s president, but in 1973 he resigned. His dream was to build his own car. He raised money from banks and private investors, and tapped 345 dealers from his contact list who each threw in $25,000. He assembled a team that included former executives from GM, Chrysler, Aston Martin, and Jaguar. He wanted a jurisdiction hungry for jobs that would hand over funding and tax breaks to get them, and he found it in Belfast in Northern Ireland.

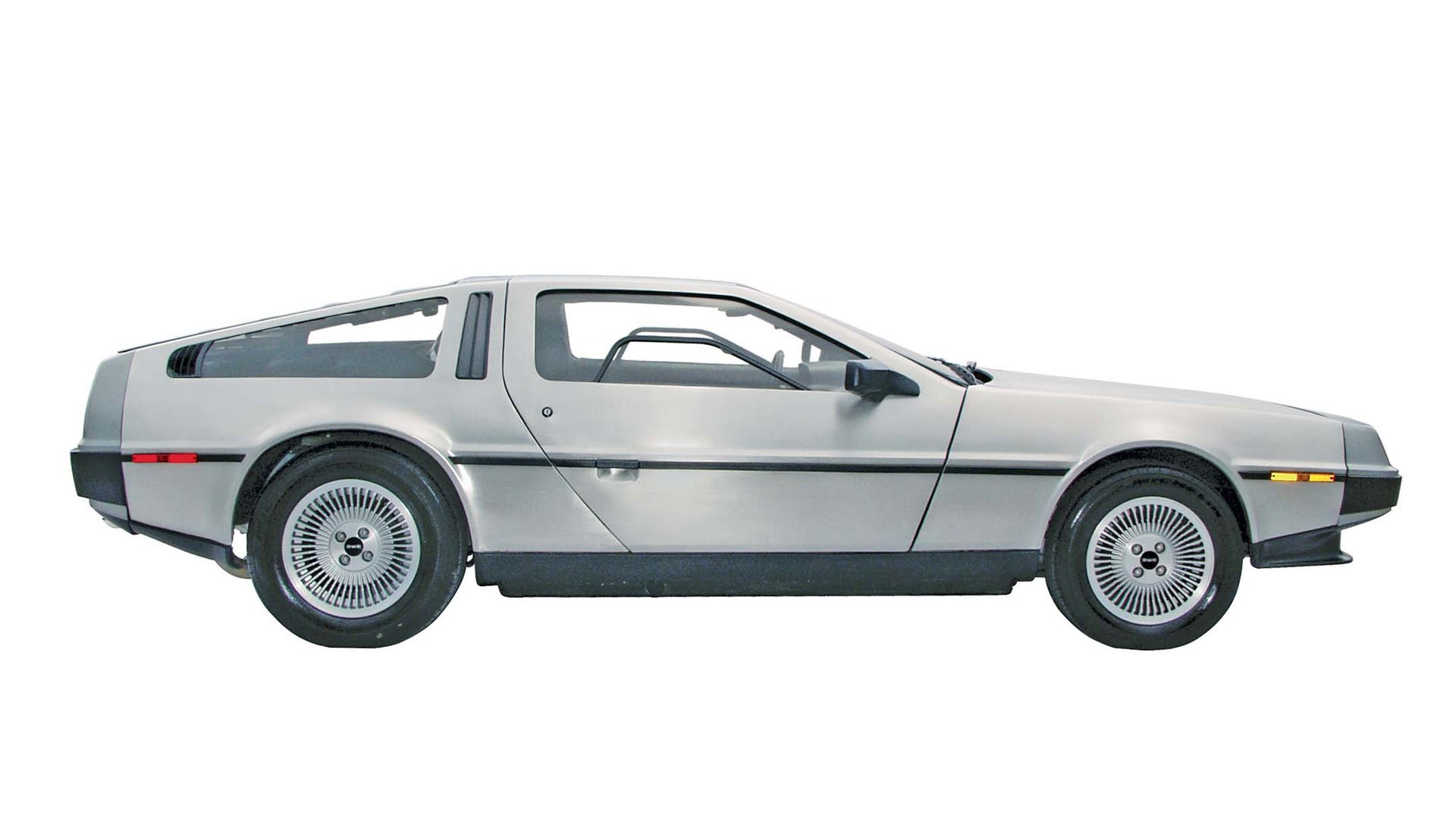

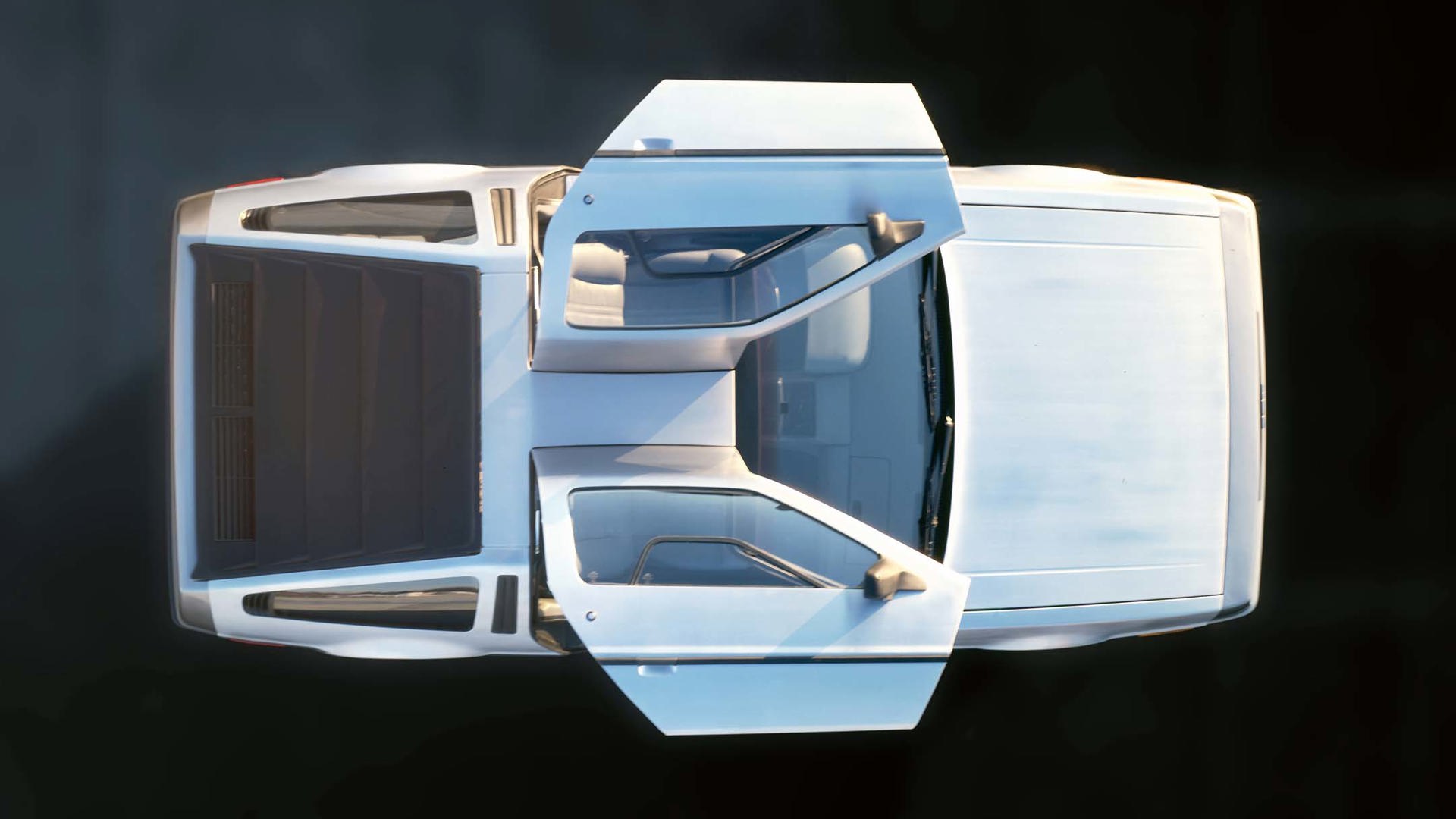

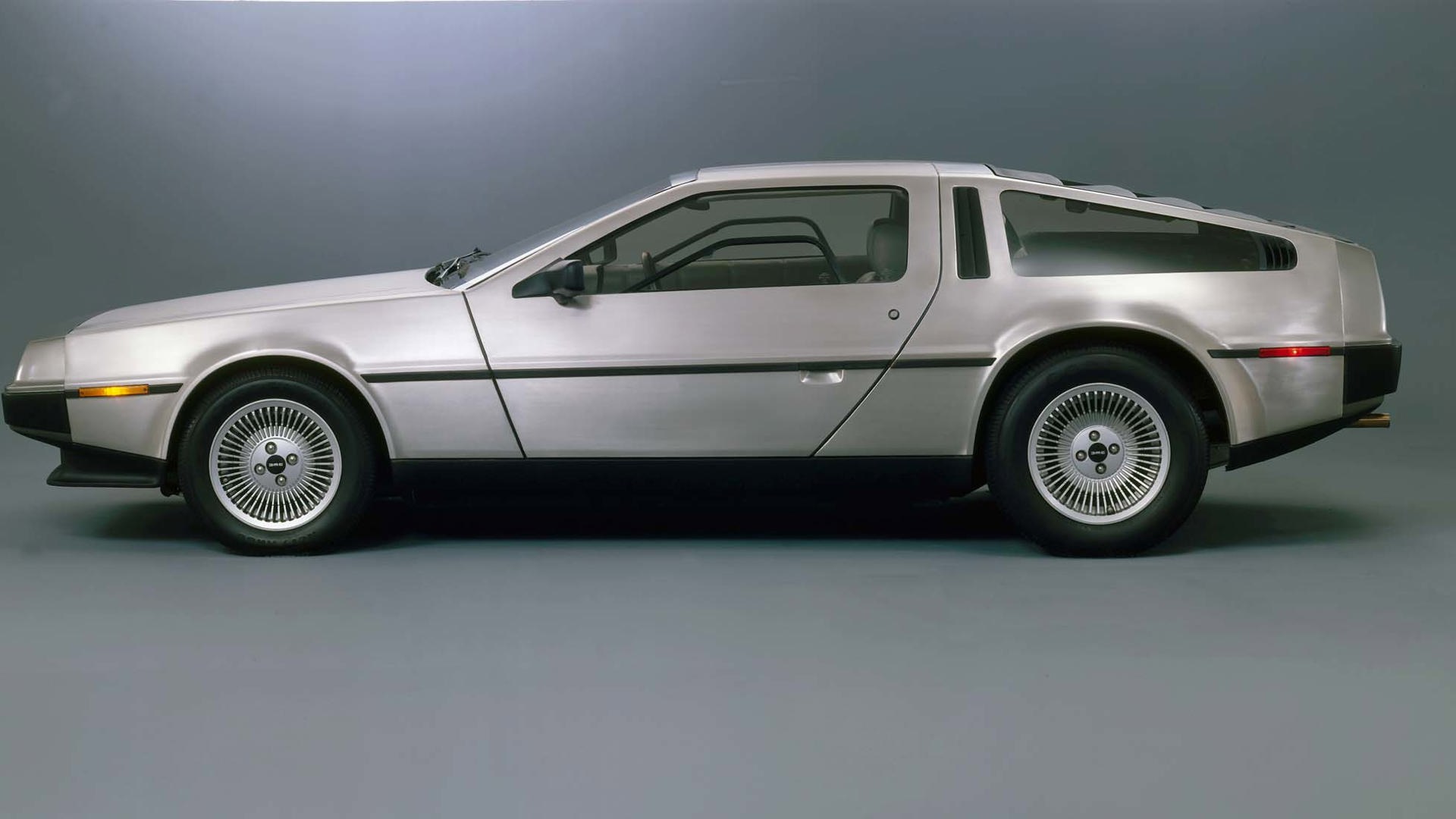

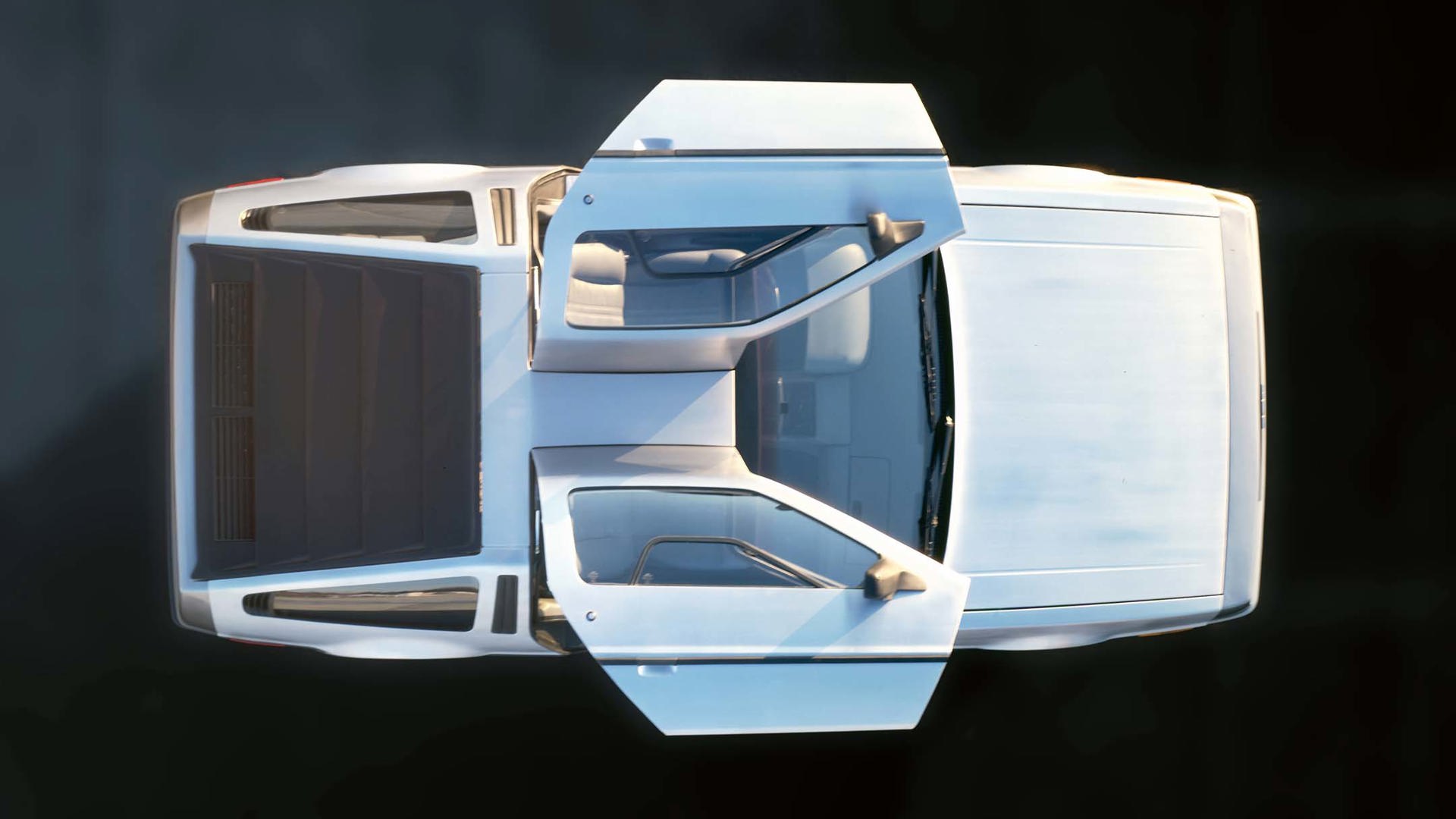

His design included gull-wing doors, a backbone frame designed by Lotus founder Colin Chapman, and an unpainted stainless-steel skin over fiberglass panels. He originally wanted a rotary engine but when it proved too problematic, he substituted a rear-mounted, fuel-injected 2.8L V6 from PRV (Peugeot–Renault–Volvo) in France.

Although the car bore some resemblance to the Bricklin, built by American entrepreneur Malcolm Bricklin in the mid-1970s in New Brunswick, it was unrelated. But it shared many of Bricklin’s difficulties, including panel fit, troublesome door mechanisms, and a novice workforce. Starting a car company from scratch is unbelievably expensive and, like Bricklin, DeLorean was burning through cash.

The cars were expected to go on sale in 1979, but production didn’t start until 1981. They were expensive and underpowered, and slow sales caused dealers to cut prices. The British government would only pitch in more money if DeLorean could match it, but a planned stock offering failed.

The company went into receivership and on October 18, 1982, the British government announced plans to close it. The next day, DeLorean was arrested in Los Angeles in an FBI sting operation, accused of attempting to buy and resell 24 kilograms of cocaine – which many believed was to finance his company. He was later acquitted, but the assembly lines never restarted. About 9,000 cars were built over two years.

“John was getting ready to take the company public, and to make the offering work, he had to be building a certain number of cars,” Espey says. “They added a second shift and they doubled production from 40 to 80 cars per day, and that ate up the working capital because they were buying materials. When they went into receivership and dropped to about one car a day, they had all this inventory and couldn’t turn off the taps with the suppliers.

“There was a company called Consolidated International that had done some secondary financing for DeLorean when he was in trouble. This was just another close-out inventory, and they bought all the completed and unsold cars, the parts, and some tooling. They sold the cars, and the leftover parts they sold to an investment group in Columbus, Ohio.”

DMC’s restoration and repair business started up not long after DeLorean went under, and bought everything when the Ohio group put the inventory up for sale in 1995. “We own everything that was left in the DeLorean factory as it closed,” Espey says, which included the name and logo, a complete set of engineering drawings for every component, and a 40,000 square-foot warehouse stuffed with parts. About the only things missing were the stamping dies, which the British government had sold for scrap.

DMC uses this inventory for its parts sales and restorations, but will also tap into it for vehicle production once it starts.

The NHTSA form is the final piece of a legislation project that’s been in the works since 2011. DeLorean and several other companies worked with SEMA (Specialty Equipment Market Association) to outline regulations for replica vehicle manufacturing. “SEMA kept running into a brick wall in Washington,” Espey says. “They would talk to senators and congressmen who didn’t know a Cobra from a GTO from a Mustang. But they discovered when they said DeLorean, everyone knows the Back to the Future car, and in 2014 things started to move fast.”

The regulation was folded into another piece of highway legislation and signed into law in 2015 by President Obama. The replica vehicle can only be registered with its year of production, not the model year of the car it mimics, and its engine must meet emissions standards for that year (meaning, essentially, all replicas will carry brand-new engines). However, the vehicle only has to match the safety standards that were applicable to the vehicle it replicates. That means any brand-new DeLorean only has to meet 1981 safety standards, and Espey says it likely won’t have anti-lock brakes or airbags.

Companies are limited to a maximum of 325 replicas annually and can’t make more than a total of 5,000 vehicles overall per year, “which keeps GM, Ford, and the others out,” Espey says. “It’s strictly low-volume. It’s companies like Superformance in California that do the Cobras and the GTs, Factory Five Racing, and ICON in Los Angeles that does the old Broncos. Even the guy who owns Checker wants to start them up again.

“If we got a phone call from NHTSA that said here’s the form, fill it in and you’re approved, we could start production in eight months and have the first car out in nine to ten months. They’re not restorations, they’re reproductions. We won’t be using any used parts, but we will use a significant number of new-old-stock parts. I’m not going to make glass when I have it in stock.”

The cars will look like DeLoreans on the outside, but will have bigger brakes and wheels, new engine, and a redesigned interior, since “most people don’t want an AM/FM/cassette in their cars anymore,” Espey says.

Some collectors fear that a new DeLorean will eat up valuable replacement parts or destroy the value of their originals, but Espey disagrees. “If you’re going to make a replica, you can’t make 98 percent of the car. I’ve got over 1,000 doors and about 1,500 quarter panels, but I have to make the left front fender, because it’s been unavailable for twenty-five years. It’s $250,000 in tooling and then the stainless will run $300 to $500 depending on tariffs. Nobody’s going to put that money into it unless you need fifty or so a year. It will improve the availability of some parts that you can only get on the used market, when you can find them.”

DMC has memorandums with suppliers for engines, brakes, and tires, but everything’s currently on hold as it waits for that elusive piece of paper to come through. “We’re not taking orders or deposits until the regulations are in place,” Espey says. “SEMA is tired of waiting, as are all the other players. We’ve got suppliers who’ve been on hold for the better part of two years, and I’ve got about 70 people I’d like to hire in Houston. We could have this cottage industry in the US with all these small-volume manufacturers if NHTSA would just create a form.”