Spoiler alert! Has there ever been a more effective visual shorthand to show that a car is ready to take on the track than the spoiler? Oh sure, huge wheels, low ride heights, and brightly coloured calipers are all heavy-handed hints that a car’s been set up by engineers for some road course work, but a spoiler is (almost literally) a giant billboard for big speed.

Unfortunately, the spoiler does also find its way onto a lot of cars that have no business in wearing one. Blame residual effects of The Fast and Furious franchise for still saddling the occasional front-wheel-drive machine with a tremendous park bench attached to the rear trunk, doing nothing other than increasing drag and looking like a bit of an eyesore.

Still, for the most part, the spoiler has purpose. Yet before it had that purpose, somebody had to figure out how to make it work. Then questions followed: more spoiler? Less spoiler? Maybe even an invisible spoiler? What should the rules of racing allow, and at what point are we just showing off? Also, can we make these things retractable? Here’s a look at the history of people spoiling their cars, on purpose.

We will Rak you

First, there’s a little matter of proper nomenclature to be raised. When we use “spoiler” as a general term, the image that comes to mind is often a be-winged Formula 1 car, gripping through a series of S-bends at furious speed, thanks to tremendous downforce. As it happens, those wings aren’t spoilers – they’re wings. The purpose of a spoiler is to disrupt (or spoil) airflow, in order to create a favourable aerodynamic effect, such as reduced lift, or improved drag.

However, because this is a history lesson, and not a physics classroom, we’ll be looking at both wings and spoilers together. That’s especially important in the early days of automobile aerodynamics, when the growing understanding of flight was used to create the first winged cars.

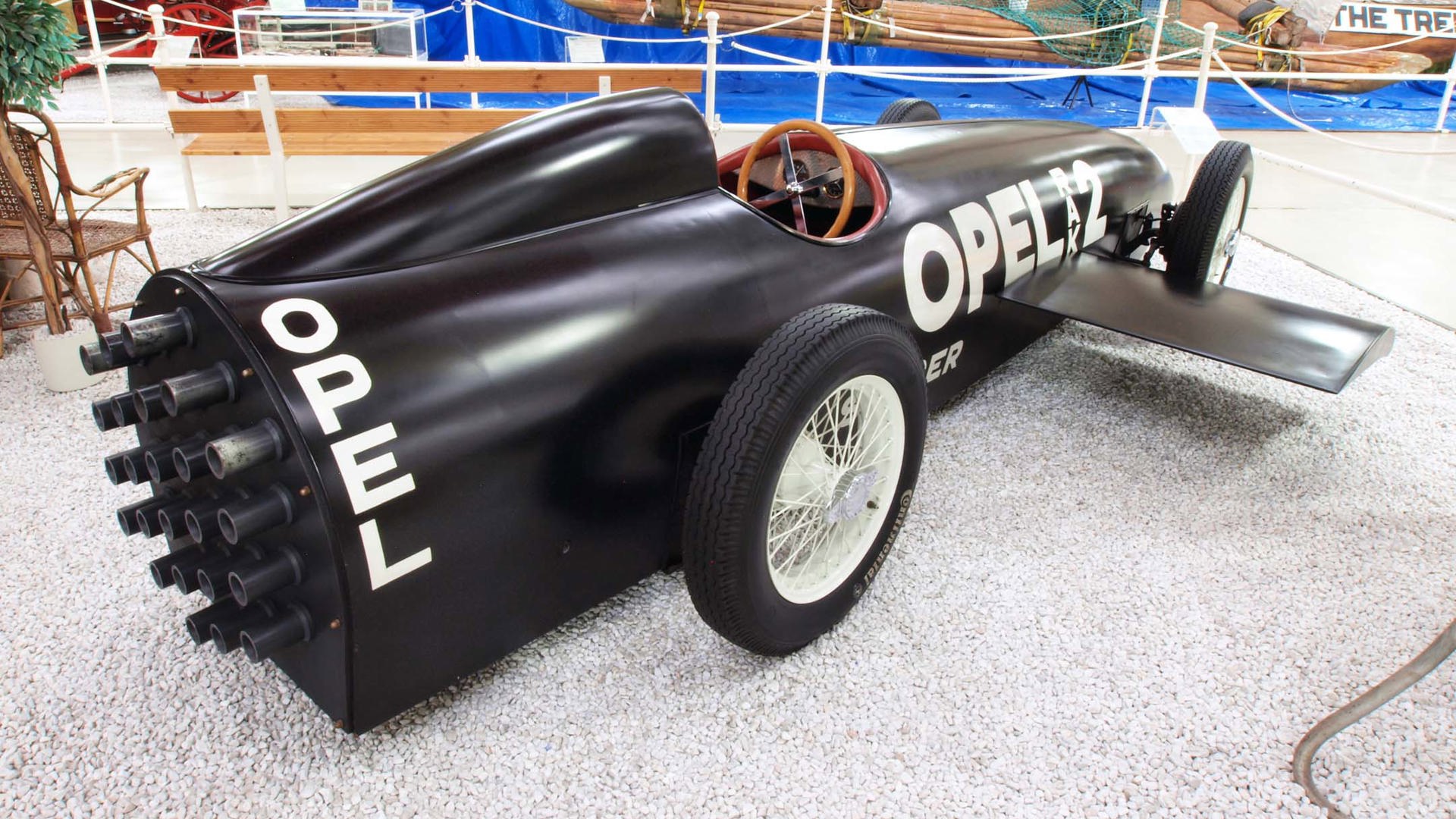

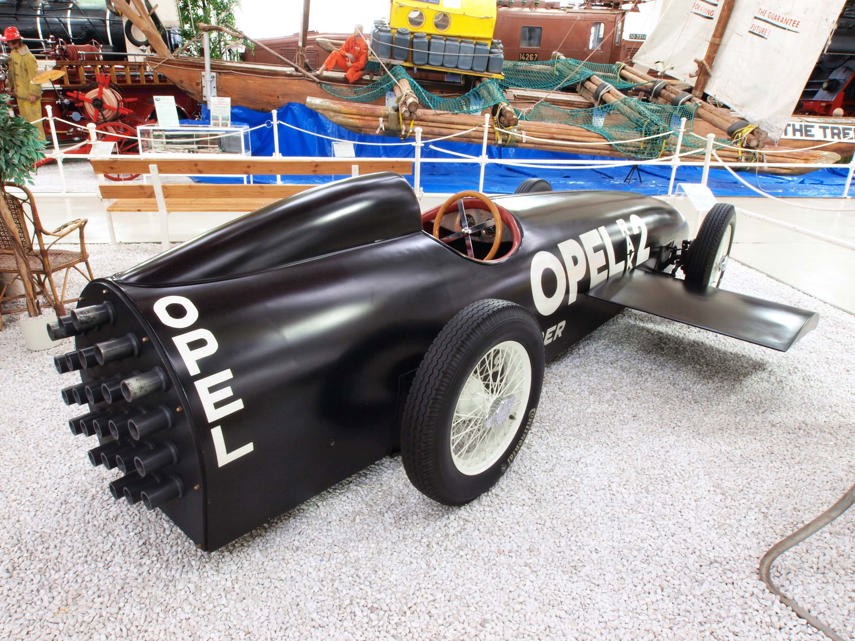

Forget your now well-known front or rear tail wings, the Opel-Rak 2 was more winged in the style of Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang. Two stubby, sharply-angled wings protruded from the midsection of this bullet-shaped land speed record car. On May 23, 1928, Fritz von Opel (grandson of the company’s founder) stepped on the accelerator and lit up 24 solid-fuel rockets, propelling the Rak 2 to 238 km/h.

Here, the winglets had no function other than to keep Opel from flying off into the air and exploding like some giant wheeled firework. It would take several decades before someone figured out that a wing could actually help you turn too.

Simplify, and add downforce

The chief difference between a wing and a spoiler is, as mentioned, the ability of the former to produce downwards pressure on a car, at the expense of drag. Greater downforce enhances stability at high speeds, and acts as a grip multiplier in the corners. First to test this theory out in practice was the Lotus 49, mid-way through the 1968 season.

The 49 was already something of a breakthrough in design for racing cars, as it used the engine and transmission as part of the structure – F1 cars have since long used this stressed-member layout. But where Lotus really opened the floodgates was with its high-mounted rear wing, eventually expanded to two stilt-like wings bolted directly to the suspension front and rear.

Compared to what modern racing machines look like, the Lotus 49 is a delicate, spidery thing that seems incredibly dangerous. The idea behind mounting the wings so high up was that they’d be cutting through air undisturbed by the airflow around the 49, or the wake of the cars it was chasing. However, as other manufacturers began to use similar wings, the struts occasionally began failing, causing serious crashes. The technology was banned, and amended to having the wings mounted to the body of the car.

Most expensive spoilers ever

However, before spoilers and wings really took off in Formula 1 racing, they were popular anti-lift devices in road-racing cars. In fact, two of the most valuable racing machines ever made featured early deck-lip spoilers: the Ferrari 250 GTO and the Shelby Daytona.

These days, of course, the 250 GTO is desired for its exclusivity and beauty, but there’s functionality to that beauty. The little kicked-up lip at the back of the car disrupts the airflow, as compared to the more rounded rump of a Ferrari 250 GT short-wheelbase. That means less rear-end lift at speed, greater stability, and a race-winning pedigree for what’s generally agreed to be the most expensive car in the world.

Likewise, the Daytona coupe took the lessons learned from racing Cobras, and added both a stiffened chassis and some aerodynamic tweaks. The development, done entirely by hand by Peter Brock, was pioneering stuff. An engineer from Convair, asked to look over Brock’s prototype, insisted that the car should be at least three feet longer for stability. However, the Daytona’s stubby spoiler did the trick, with test driver Ken Miles taking the Daytona to nearly 300 km/h on his first test laps.

Attacking from all angles

Peter Brock would later go on to have a fascinating career, and is perhaps best-known for making Datsun a household name in racing circles. His Brock Race Engineering (BRE) company did very well in SCCA racing, and before that he had developed a little-known racing car called the Hino Samurai, which featured an adjustable wing.

As we’ve talked about, a wing exchanges drag for downforce. In the twisty parts of a racing circuit, you want all the downwards pressure you can get. On the straightaway, as little drag as possible is wanted. So what if you could get your wing to flip up and down like the flaps of an airplane?

Enter Chaparral, probably the cleverest bunch of racing engineers in the wild west days of aerodynamics. Their Chaparral 2E, an evolution itself of a successful GT racing car, featured a huge rear wing, a ducted nose intake for added grip, and three pedals – but not the three you’d expect.

Debuting in Can-Am racing in 1966, the 2E featured a 450 hp Chevrolet 327 V8 with quad carburettors, and an automatic transmission. The third pedal, located on the far left, allowed the driver to vary the angle of attack of the high-mounted wing, from a full 110 kg of downforce, to a low-drag 4- or 5-degree flat profile when the track was straight.

The 2E managed a healthy 1–2 finish at Laguna Seca, but just as with F1, failures in high-mounted wings led to a ban on variable attack aerodynamics. Chaparral wasn’t done yet, and invented the 2J, which featured a sort of invisible wing/spoiler of sorts. Instead of relying on aerodynamics, the 2J had a separate two-stroke engine driving a pair of fans, which allowed it to suction onto the road like the racing version of a vacuum cleaner. Why not? The rulebook didn’t say they couldn’t. Chaparral only got away with running the 2J for one season, but it remains one of the most unusual racing cars ever made.

Track-style on the street

Probably the most famous wing to appear on the roads arrived in 1970 with the Plymouth Superbird. A special aerodynamics package for the Roadrunner, it featured a cone-shaped nose with pop-up headlights, and a hugely tall rear wing. With Richard Petty at the wheel, its racing variant was quite successful in Nascar, although the car wasn’t as strong a seller as Plymouth had hoped for. These days, like anything Mopar related, it’s a collector item.

The other iconic big rear wing/spoiler of the 1970s was the Porsche 911 Turbo. First arriving in 1975, the famous “whale-tail” provided more cooling air to the engine, and also helped high-speed stability above 100 km/h or so. Of course, you don’t want to just bolt on a whale-tail to your standard 911 for the look, without at least considering a Turbo-style front spoiler to keep things balanced front-to-rear.

As with the racing successes in the 1960s, the addition of wings and spoilers to successful road cars opened the floodgates. Practically anything with any performance appeal had to have a huge wing in the 1980s, whether it was the boxy rear spoiler on the back of an IROC-Z, or the snowshovel bolted to the rear of the Ford Sierra Cosworth.

Did every one of these tall tails help the cars they were attached to go any faster? Probably not. Most aerodynamics enhancements only really begin to take effect at speeds well above highway pace. The popularity of people swapping the big wings of their Subaru STI for simple lip spoilers probably didn’t slow those Subies down one bit.

The future of peacocking

These days, most performance cars come with active aerodynamics, including electronically controlled grille shutters, and variable-height rear wings and spoilers. You can credit the German marques for being first to the party here, as the Volkswagen Corrado’s electrically-raising rear spoiler brought things to the masses. The Porsche 911 has had a power rear spoiler for decades.

The problem with these deploying rear spoilers is two-fold. Since they only pop out above a certain speed, what better way to advertise that you might be driving a bit too quickly? Even worse is the tendency for certain show-off-y types to drive around with their spoilers fully deployed, even in parking lots. If leaving your fuel filler door open is the unzipped fly of the automotive world, then a deployed spoiler on a parked Panamera is the popped collar of cars.

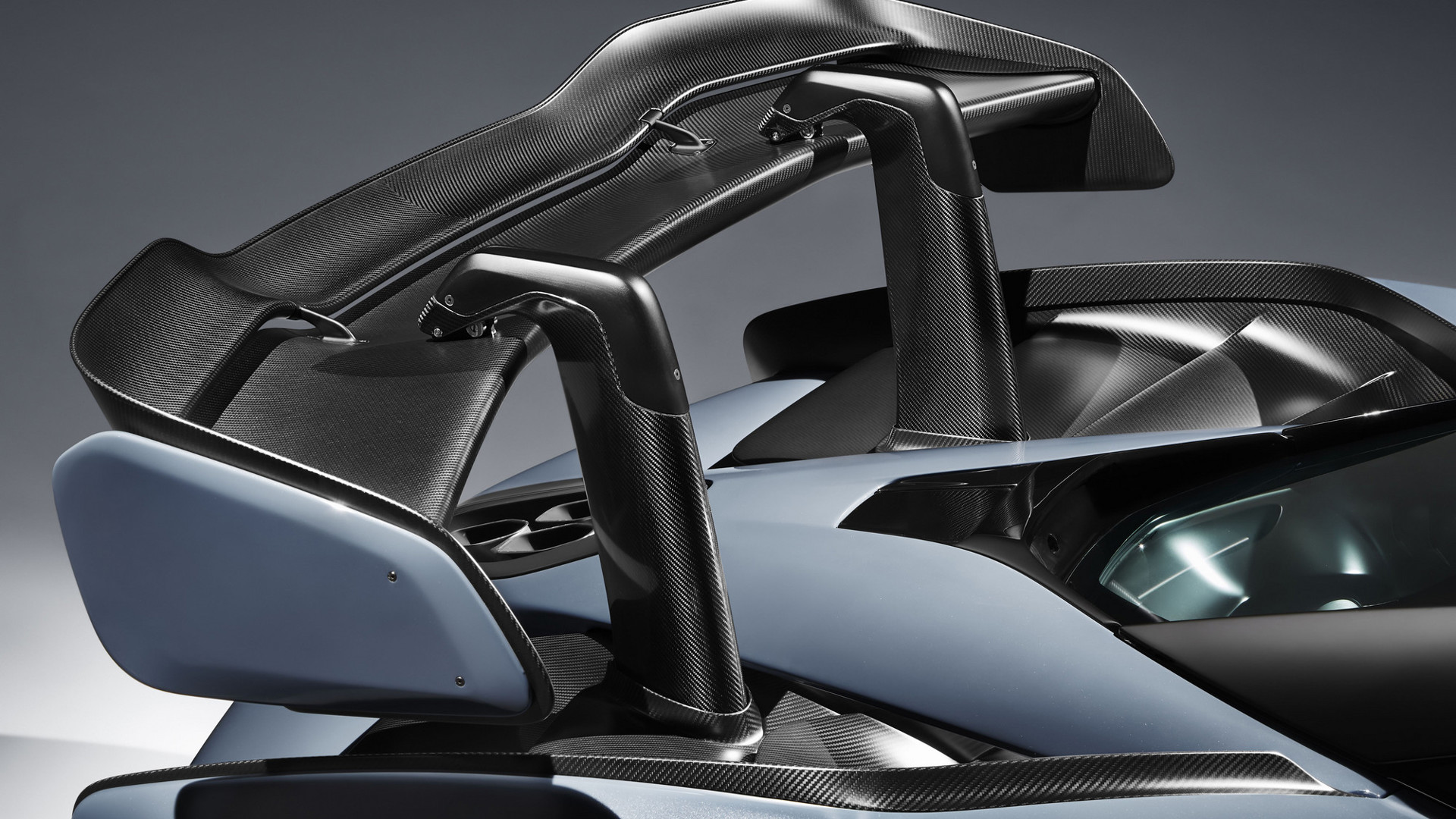

And spoilers and wings seem to be getting ever more outrageous. The current champion has to be the McLaren Senna, which doesn’t look particularly pretty, but features an absolutely massive and functional rear wing. It’s like a racing car built without a rulebook to follow.

Do you actually need that rear spoiler? Manufacturers like Porsche and Subaru don’t seem to think so. Yes, you can buy a 911 GT3, but wouldn’t you prefer the Touring version for a little cleaner look? And, when optioning your STI, there’s no more need to set up a forum meet to swap trunk lids around. Just order your car with or without the big wing, no extra charge.

As for whether spoilers will continue to be part of our daily driving lives, there’s certainly a stubby little one on the back of the Tesla Model X, and the carbon fibre industry is struggling to keep up with the desires of youths to bolt Cessnas to the back of their Scions. Let’s face it, car culture has been spoiled for a long time.