HALIFAX, NS – It’s only 144 km from the Halifax Airport to Wallace, NS, a straight shot up the 104 then a 45-minute jaunt on N-307. We could have done it in an hour and a half – but where’s the fun in that?

Instead, we made a clockwise circuit around the upper half of the province – a most inefficient route, to be sure, but ultimately one that proved most satisfactory. Adding six or seven hours of travel time to the day is normally something that seasoned travellers shudder to even think about; but since we did it while driving 2018 Porsche 911 Carreras, each hour was embraced, rather than endured.

We were part of a three-day road trip in a convoy of eight Porsches, that would culminate in driving the Cabot Trail – a 297 km loop around the tip of Cape Breton island, considered a rite of passage for driving enthusiasts.

We were a disparate group, to be sure. Most were clientele of Porsche Canada who’d paid $3,749 plus tax per person for the experience – and ranged from a high school football coach on a bucket-list adventure, to owners with multiple cars in several garages. And then there was us, the media; though we no longer identify as ink-stained wretches, we were enjoying a free ride in exchange for our role as chroniclers.

Each day began promptly at 9:11 (get it?), at which time we were on the road in a well-organized, multi-coloured convoy. Our eight-car lineup consisted of two sub-groups of four, each led by an instructor. As luck would have it, we drew Kees Nierop as our fearless leader – an illustrious Porsche racer; a veteran of the 24 Hours of Le Mans and Daytona, whose career highlights include winning the 12 Hours of Sebring; and the only Canadian to have his name on a factory race car in the Porsche Museum in Zuffenhausen, Germany.

Ours was not a sightseeing trip – a leisurely cruise around the Maritimes with numerous stops to browse the wares of local craftspeople and tchotchke vendors. With over 500 km to cover before sundown, it was a well-regimented, lead-follow Cannonball Run–style tear through some of the prettiest countryside ever to go whizzing past my windows. We weren’t given route books, nor pre-programmed nav system guidance; for duration of the trip we were instructed to maintain our position in the convoy, and never let the cars in front out of sight. But we were connected by radio, a lifeline that delivered basic driving tips, historical lore, and an abundance of colourful stories from the charismatic Kees, who’d once delivered flowers to Barbra Streisand while between racing gigs, and whose Porsche Cayenne Desert truck had managed to fully disgorge its engine while somersaulting down a sand dune during the 2007 TranSyberian Rally.

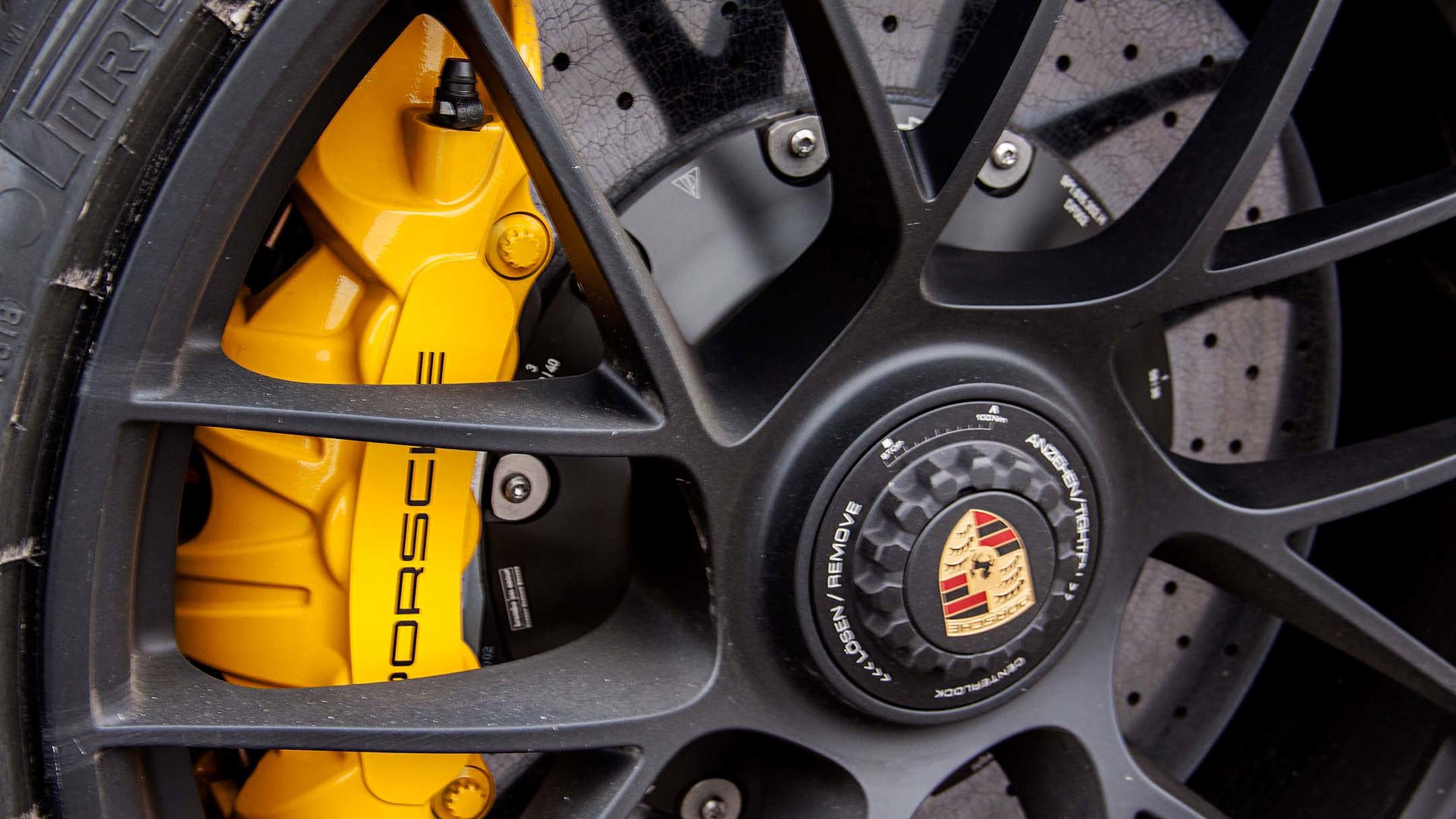

The cars were divided evenly into two groups – the first of which were Porsche 911 Carrera GTS in agate grey, and the second – ours – was made up of racing yellow Carrera S. The instructors drove a pair of white Carrera S with highly visible green and yellow racing stripes.

All but the instructor’s cars were equipped with the dual-clutch Porsche Doppelkupplung (PDK) automatic transmission, which of course elicited the predictable moans of frustration from the enthusiasts in the group – none of whom could ever hope to match the Gatling gun precision of the PDK – and relief from the instructors, assured that all cars would still be operable at the end of the day.

We sat happily two cars behind Kees, second from last in the convoy, and well-removed from the testosteronic enthusiasm of the first group – whose questionable passing manoeuvres and disregard for the posted speed limit suggested they’d forgotten we were travelling on public roads.

My driving partner, Arlene, a managing editor with a well-known Toronto magazine, was upfront about not being a car fanatic – a blessed relief since we’d be spared the interminable bench-racing, and travelogue one-upmanship that inevitably happens among automotive media.

“I don’t get it,” she said. “My husband goes on about engine sound – how can a car sound good?”

“Push that button,” I replied, downshifting, “the one that looks like two eyeballs on a cartoon owl.”

The sport exhaust barked and popped, a raspy echo that bounced off the rock face beside us.

“What was that?” asked Arlene.

“That, my friend, was the glorious sound of a twin-turbo flat six dumping its unspent fuel.”

“Oh,” she said. “I think I get it.”

Our bright yellow Carrera S packed 420 horses beneath its tapered hood, and put 368 lb-ft of torque to the pavement through the rear wheels. The leather wrapped cockpit is snug without being cramped, with just enough room in the rear seats for knapsacks, and two roller bags in the “frunk”.

The 911 has a well-deserved legacy as one of the most athletic race cars on the planet, but it’s an easy car to drive at a relaxed pace too. Accompanied by Kees’s constant “keep your eyes up” mantra, we put great, looping miles behind us in one continuous flow.

Our first stop was Peggy’s Cove, the postcard-perfect fishing village that’s become the quintessential Nova Scotian icon, and one of the biggest tourist draws in the country. It also marks the site where 20 years ago last August, a SwissAir jetliner plunged into the ocean after suffering catastrophic electric failure, killing all 229 people aboard.

It’s beautiful but unspeakably packed, crawling with tourists and busier than Times Square on New Year’s Eve. Our visit was mercifully short – after a brief bio break, we returned to our cars and were back on the road.

The scenery is spectacular. Rolling hills blaze with a tapestry of autumn colour, which gives way to rugged coastline, rich with UNESCO heritage fossil deposits thanks to some of the world’s highest rising tides. We rolled through pastoral farmland – fields studded with pumpkins, tiny villages of clapboard houses, and lunched in Lunenburg County surrounded by colourful pottery and painters’ studios.

I feel a sense of guilt, a squeamishness at being part of such an ostentatious display of privileged wealth, especially when cruising through areas such as this one, impoverished by the collapse of the fishing industry. But if there was resentment behind the beaming smiles, they hid it well. We were all delighted by the tiny boy, perched on his father’s shoulders, and waving both arms frantically as we paraded by. Many stopped and posed for selfies, curious about our destination, and wishing us well. One young man could barely contain his excitement, rushing to and fro, snapping pictures, exclaiming that it wasn’t every day that “two million dollars’ worth of cars” passed through their town.

My favourite was the woman who rolled down the window of her pickup to caution us to “watch for moose” – her smile in no way diminished by the absence of upper teeth. “Youse could probably just drive underneath them anyway.”

After overnighting at the pretentiously named, but luxuriously appointed Fox Harb’r resort in Wallace, we set out promptly at 9:11 for Cape Breton. We’d traded our Carrera S for a GTS model, which boasted a wider set of haunches, lower ride height – and most importantly, 450 hp and 405 lb-ft of torque.

Until 1955, Cape Breton was an island, at which point it was joined to the mainland by a causeway built from ten million tonnes of blasted granite. The Celtic influence of the island’s original Scottish settlers is everywhere, in the Gaelic road signs, and the “ceilidhs” or Celtic musical festivals in seemingly every pub and church basement. We stopped for lunch at Glenora Distillers, producers of the first single malt whiskey in North America, but our sampling was restricted to a crisp, beer-battered fish-and-chips lunch accompanied by live folk music.

By this time, the hurricane that had battered Florida’s panhandle had worked its way up the coast and we were being lashed by the tail end of it. Our route would take us clockwise around the Cabot Trail, placing the coastline on the driver’s side, and I was more annoyed by the weather’s effect on the view than on the driving conditions. All cars were equipped with Pirelli P Zero tires – terrific tires on dry pavement, but only moderately capable in the rain due to their shallow evacuation channels. Kees advised us to avoid the wettest part of the road, riding the crown where possible to lower the risk of hydroplaning.

There aren’t really any marked differences in the cars at these speeds. The GTS’s sport seats were more aggressively bolstered, which we actually found more comfortable, but the extra power was no problem on the slick roads as long as you kept the throttle modulated and the braking smooth. Our particular car was equipped with the optional $9,730 carbon-ceramic brakes, powerful but inherently grabby brakes requiring conscious effort from the driver to remain smooth.

The road dips and curls, folding back upon itself as it climbs its way up the cliff’s edge. Occasionally the rain cleared, and we were rewarded with spectacular views of the rugged coastline, and great, rolling waves crashing below. The trail was named after John Cabot, or Giovanni Caboto, who reportedly discovered Cape Breton in 1497, although the indigenous Mi'kmaq already in residence would probably dispute that claim. After passing through Cheticamp, a predominantly French Acadian fishing village, we wound our way around the coastline to Ingonish and the Keltic Lodge, a historic resort on the very tip of Cape Breton.

Our final day dawned cold, wet, and miserable, and we had over 400 km between us and the Halifax Airport. But with seat warmers employed, we were warm and cozy within the Porsche’s cabin. These cars gobble up the miles effortlessly, and it’s easy to see how these Experience events showcase their usability. The 911 can make the average driver feel like a hero, yet easily adapts to a leisurely cruise – or a marathon three-day dash around a remote, maritime coastline.

For more information on Porsche Experience, see http://porscheexperience.ca/en/