Just as some people are more suited to a sports car while others are better off with a minivan, there’s no “one-size-fits-all” when it comes to electrified vehicles. You need to consider where you’re going to drive it, and how to charge it if it has a plug.

We’ve rounded up the different types, how they work, and the buyers they’re most likely to fit.

Hybrids (HEV)

How they work

Hybrids combine a gasoline engine with an electric motor and battery. They automatically switch between gas, electricity, or a combination of the two, depending on power requirements. This includes running solely on battery when you’re creeping in traffic, or the electric motor adding a fuel-free power boost to the gas engine when you’ve got your foot down.

They’re self-charging and don’t get plugged in. They use regenerative braking to recharge – when you’re slowing down, the system captures that kinetic energy and stores it in the battery. They will also use the engine’s power for recharging when required.

Hybrid vehicles include the Toyota Prius, Camry Hybrid, Corolla Hybrid, RAV4 Hybrid, and Highlander Hybrid; Kia Optima Optima; Hyundai Ioniq Hybrid; Honda Insight, and Accord Hybrid; and Ford Fusion Hybrid, among others. A few hybrid SUVs have all-wheel drive, such as Toyota’s new Prius AWD-e.

Who’s best for them?

As long as there’s gas in the tank, you’ll get where you’re going (although a hybrid won’t drive on electricity alone if you run out of gas). They’re the best choice for those who drive long distances, or those who live in apartments or only have street parking, where plugging in isn’t possible.

They’re usually pricier than comparable gasoline-only vehicles, and most are lighter-duty. If you tow a boat or trailer, be aware that most have a maximum of about 5,000 to 7,500 lb capacity.

Plug-In Hybrids (PHEV)

How they work

Once a rarity, PHEVs are now offered by a number of automakers. They’re hybrids with a plug and extra battery capacity for additional electric-only operation.

After you’ve charged a PHEV, it can run exclusively on electricity. When that charge runs out, it reverts to conventional hybrid operation, and self-charges its hybrid battery as it does.

That’s the basic premise for all of them, but the details can differ between the various models. The electric-only portion can range from around 20 to 80 kilometres. Most use up the stored charge first, but some have selectable modes where you can “save” that electricity for optimum use – such as using hybrid operation on the highway, and switching to electric-only when you’re back on city streets.

Unlike an all-electric car, you don’t have to plug in a PHEV. If you forget, or you can’t find a plug, the vehicle will still run as a conventional hybrid. However, most are pricier than regular hybrids, and it doesn’t make sense to spend extra if you can’t regularly plug it in at home or at work.

Plug-in hybrids range from small cars like the Toyota Prius Prime, Ford Fusion Energi, Honda Clarity, and Hyundai Ioniq Electric Plus; to sport-utilities like the Mitsubishi Outlander; and to luxury models like the Porsche Panamera and Cayenne E-Hybrid, BMW 530e, and Mercedes-Benz GLC 350e. There’s even a minivan, the Chrysler Pacifica PHEV.

Who’s best for them?

Because PHEVs have relatively short electric-only ranges, some people think, “Why bother?” But for those whose daily commutes are within that range – and according to statistics, that’s the majority of Canadians – it’s possible to do it on little or no fuel at all. It can then take you to the cottage on weekends, or across the country on vacation, without the need for a plug.

PHEVs require only a fraction of the time needed to recharge a battery-only car. It’s possible to replenish the stored charge overnight from a 110-volt outlet, so you don’t need a home charger. You can still use a 240-volt charger for quicker top-ups, though, although most aren’t equipped for DC fast-charging.

Mild Hybrid

How they work

Mild hybrids use an electric motor and battery, but only in conjunction with the engine. They’re not capable of running on electricity alone.

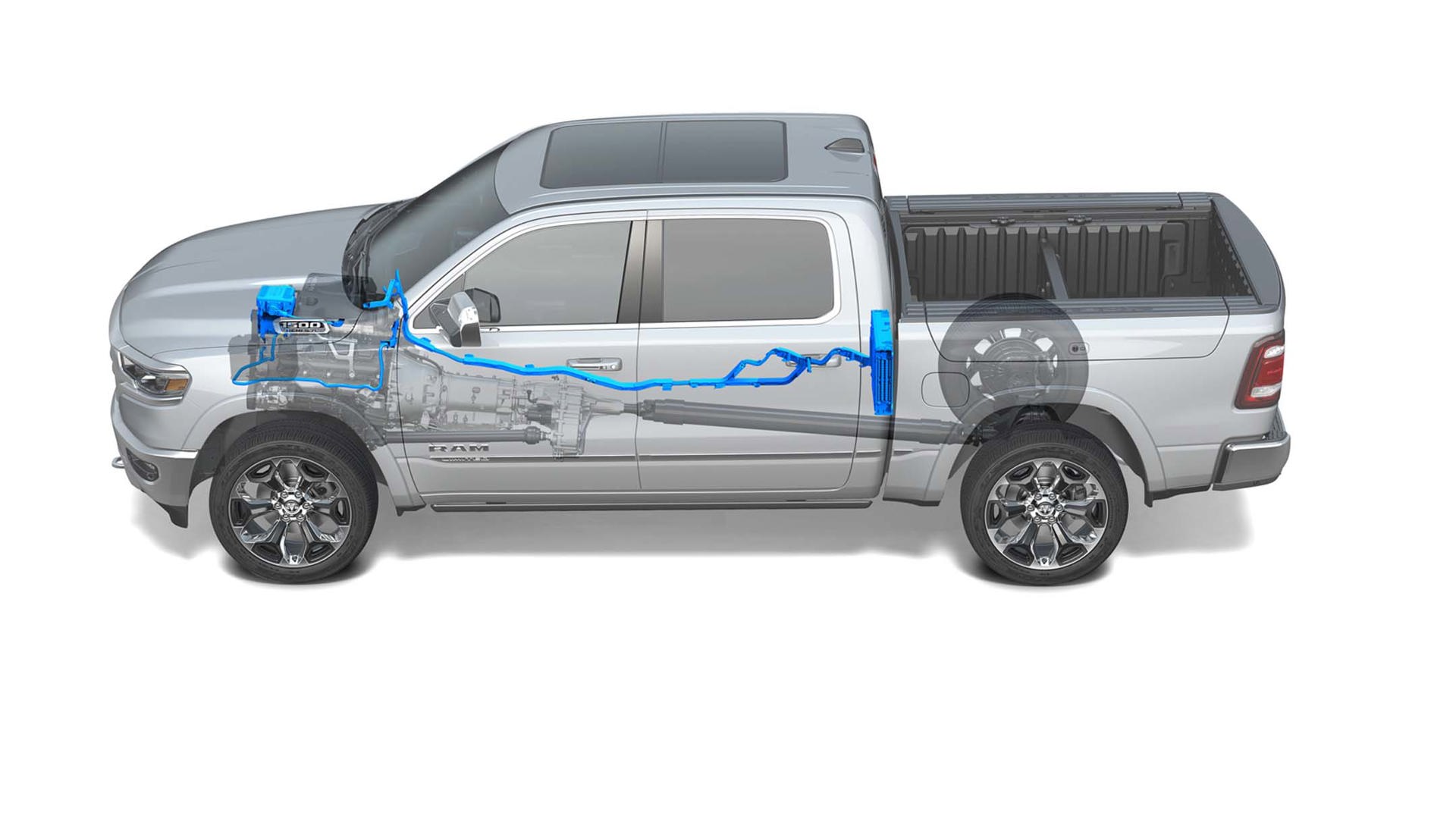

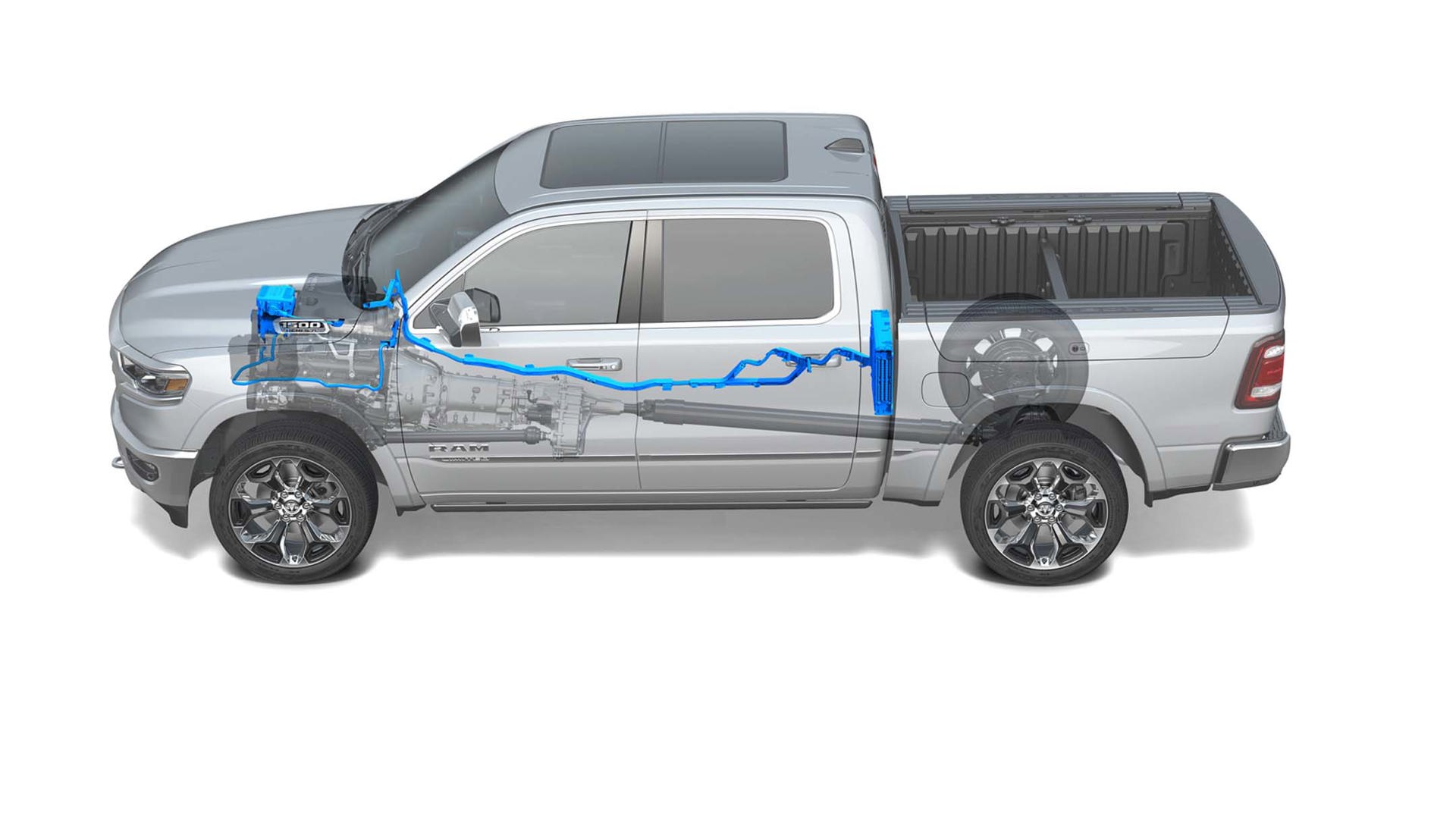

They were always relatively rare – past models included the original Honda Insight, and versions of the Chevrolet Impala and Silverado. About the only system available now is eTorque, standard on the 2019 Ram 1500 with V6, Jeep Wrangler with four-cylinder, and as an option on the Ram 1500 V8.

Older systems boosted the engine’s output when more power was needed. With eTorque, the electric motor primarily tucks in some electric power when engine speed drops and rises during gear changes, for smoother operation and a slight boost in fuel economy. It does this automatically, without any input from the driver, and recharges the battery itself.

Who’s best for them?

Since it’s part-and-parcel on certain Ram and Jeep models, you’re getting it anyway. If you’re looking at a Ram V8, it’s for drivers who like the extra smoothness and who don’t mind paying the extra cash for it.

Extended-Range Vehicles

How they work

These are electric cars with small gasoline engines. They get plugged in, and offer a longer electric-only range than a plug-in hybrid. When that stored charge runs out, the gasoline engine starts up, but it doesn’t power the wheels.

Instead, it acts like a generator, producing electricity to power the electric motor. As long as you have gasoline, you’ll get where you’re going. The Chevrolet Volt is the best-known example, while the BMW i3 electric car can be ordered with an optional range-extending engine.

Who’s best for them?

Extended-range vehicles are between plug-in hybrids and electric cars – there’s more range than a PHEV, but you’re not stuck if you can’t recharge. The ideal extended-range buyer has a longer commute than a PHEV driver, but they can still take it on longer drives without worrying about a plug. But if you want the Volt, you’ll need to buy soon, because it’s being discontinued.

Battery-Electric Vehicles (BEV)

How they work

BEVs run only on electricity – you plug them in, and they run on that stored charge. They also collect some energy through regenerative braking when driving, although not enough to turn them into “perpetual motion machines”.

How long they’ll go on a charge depends on several factors, including the battery capacity, how and where you drive it, and ambient temperature. All-electric models include Tesla, Chevrolet Bolt, Nissan Leaf, Ford Focus Electric, and BMW i3.

Who’s best for them?

Battery-electrics are ideal for the shorter distances of inner-city commutes, especially since they spew no emissions when you’re sitting in traffic jams. However, not all downtown condo-dwellers have plug-in facilities in their buildings.

For suburbanites who can plug in at home, they can be excellent choices as second cars for shorter trips. You need to buy and install a 240-volt home charging station, since it’ll take more than a day to fully charge one from a regular 110-volt outlet.

They’re not great for long-distance commuters. There still isn’t a lot of charging infrastructure, and even a DC fast-charger (if you can find one) takes at least 15 minutes to replenish a depleted battery – and that’s if you don’t have to wait for someone ahead of you to “fill up” first.

Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles (FCEV)

How they work

FCEVs are electric cars that make their own electricity inside a fuel cell, using an on-board supply of hydrogen. You don’t plug them in, and their only emission is water vapour. Refilling with hydrogen takes about the same time as filling a gasoline vehicle. Examples include the Toyota Mirai and upcoming Hyundai Nexo.

Who’s best for them?

Fuel-cell vehicles are rare, mostly because there are very few places to buy hydrogen. They’re offered only in very limited areas, most of them in Quebec and BC. Until infrastructure improves, customers will have to live close to a refuelling station, and plan trips so they don’t end up too far away when their hydrogen gets low.