Back in the 1930s, Harley Earl had a request. He was in charge of design at General Motors, and he asked his department to come up with one-off car for display.

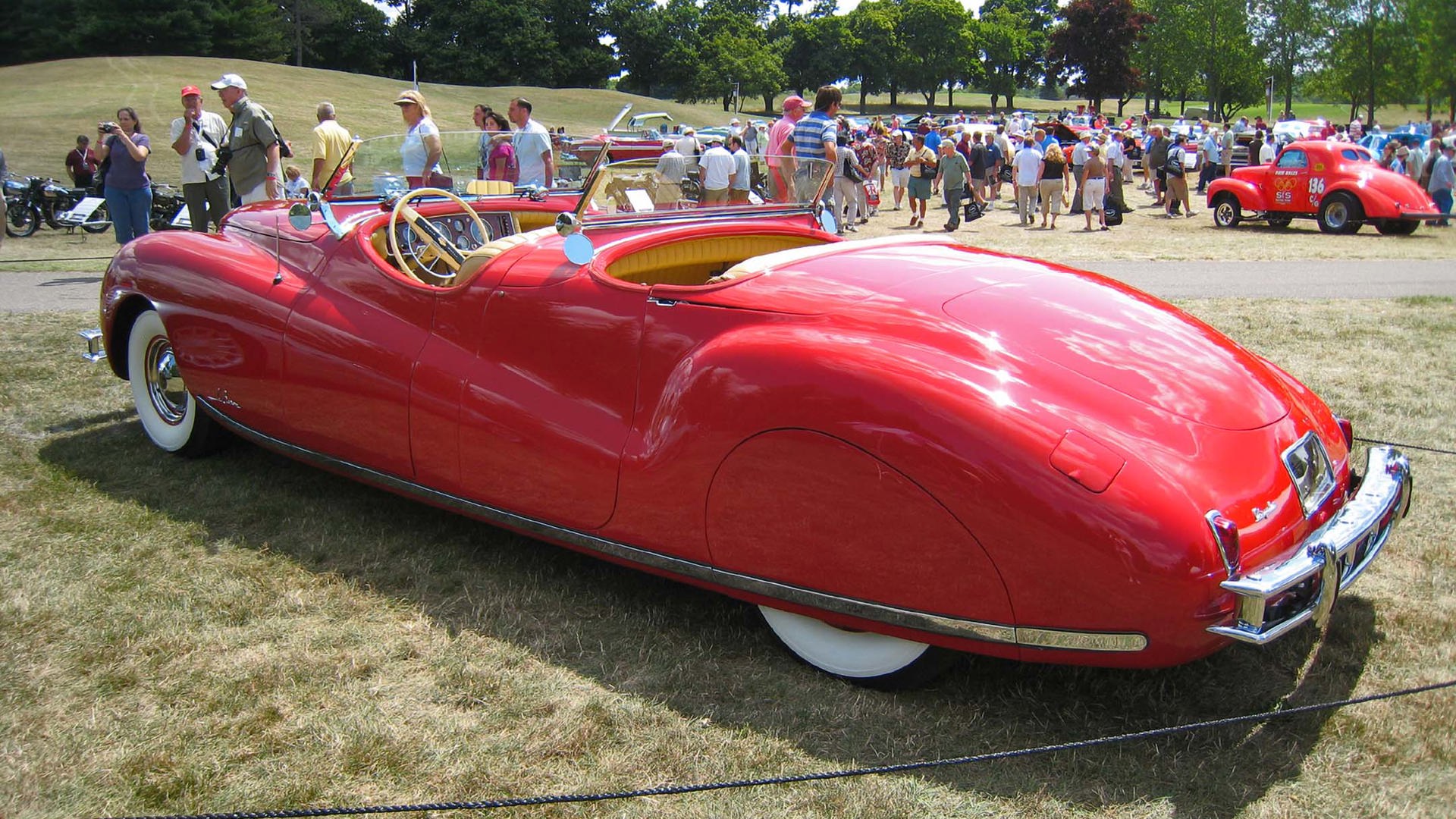

Built in-house and dubbed the Buick Y-Job, the car had several features most vehicles of the day did not, including flush-mounted door handles, disappearing convertible top, hidden headlamps, power windows, cooled brake drums, and no exterior running boards.

The Y-Job debuted at the 1939 New York Auto Show as part of a campaign to highlight GM’s styling. After that, Earl drove it for years as his personal car. But after some of the Y-Job’s styling cues made their way to production cars, and Earl turned out other futuristic show models, it became known as the first concept car.

For Earl, who was also the first to make full-size clay models to develop his designs, the overall idea wasn’t new. All designers came up with new and sometimes unconventional ideas that they added to their projects. But with the Y-Job, all these new elements were combined on a car that was never intended for production, just for show.

As for its odd name, the story goes that most military designs were known as “X-Projects” during their development, and those working on the car went a step further with “Y-Project”. Earl shortened that to “Y-Job”, and it stuck.

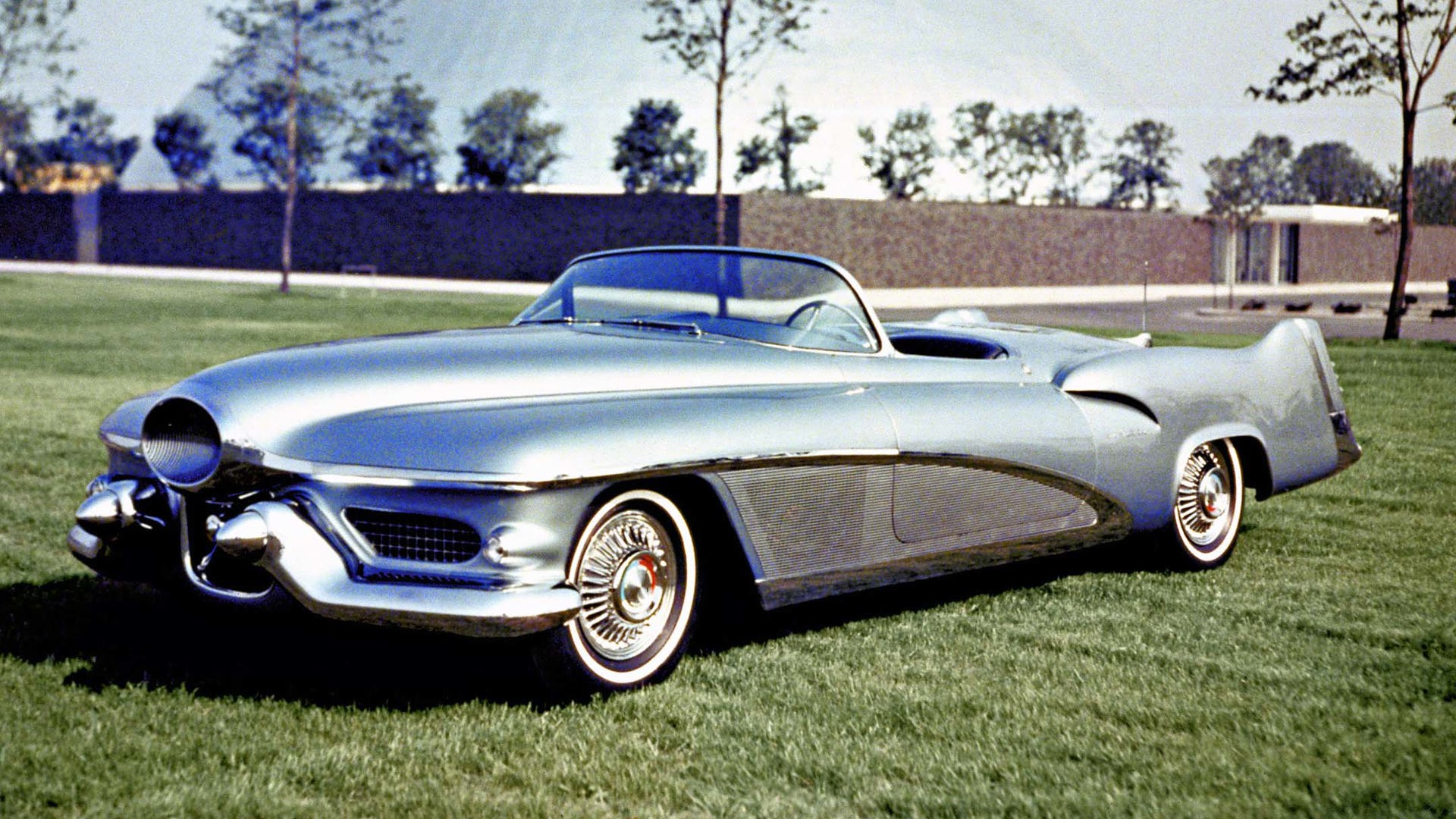

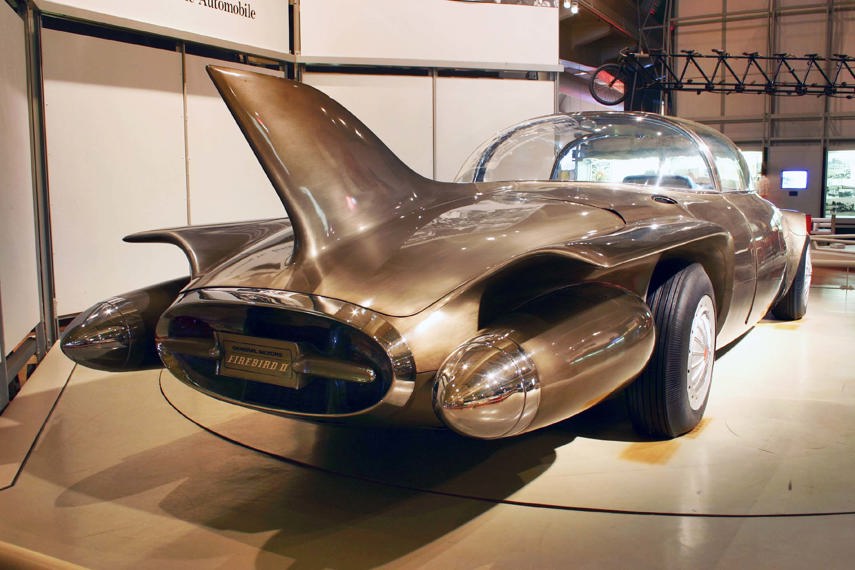

The Second World War brought a temporary halt to car production as automakers switched their factories to war materials, and all had a “gentlemen’s agreement” not to work on any new designs during the shutdown. Once things started back up, though, concept cars became a hot ticket in the 1950s and 1960s.

Concepts had a few reasons for being. Designers could try out numerous styling cues at once, and it was common for one concept to give several items to production cars – a tailfin here, a piece of chrome there. They could be used to judge public reaction to new ideas. And they were taken to auto shows, to draw spectators to the company’s display.

Not every concept was a complete car. Design studios also mocked up interiors, although these usually stayed in-house for the company’s use. For that matter, not all concept cars were intended for the public. Many stayed in the studio, used as test mules for upcoming production models.

There were a lot of concept cars, and unfortunately for automotive history, not everything could be kept. Some deemed important enough were saved – the Y-Job is still around, and regularly displayed at shows. Many contained proprietary technologies, and were crushed to prevent them getting into the hands of competitors. And several were just parked somewhere on the property, often with parts picked off as needed for the next project.

That was the fate of the 1955 Lincoln Futura. Designed by Bill Schmidt, chief stylist for Lincoln-Mercury, it was built in Italy by coachbuilding firm Ghia. Its $250,000 price tag included paint made iridescent with fish scales.

It was repainted in 1959 by car customizer George Barris and used in a Debbie Reynolds movie, but afterwards was parked and forgotten. A few years later, Barris was asked to build a car for a new television show called Batman. He bought the car, supposedly for a dollar, and turned it into the Batmobile. He eventually built five replicas that toured the show circuit, and in 2013 he sold the original Futura-based one for $4.2 million.

What makes concept cars so interesting for designers is that they’re not hemmed in by the realities of mass production or practicality. Handmade panels can swoop and swirl, and any material is fair game. In 2008, BMW debuted the GINA Light Visionary, a stunning roadster covered in a fabric skin that stretched out of the way when the doors were opened.

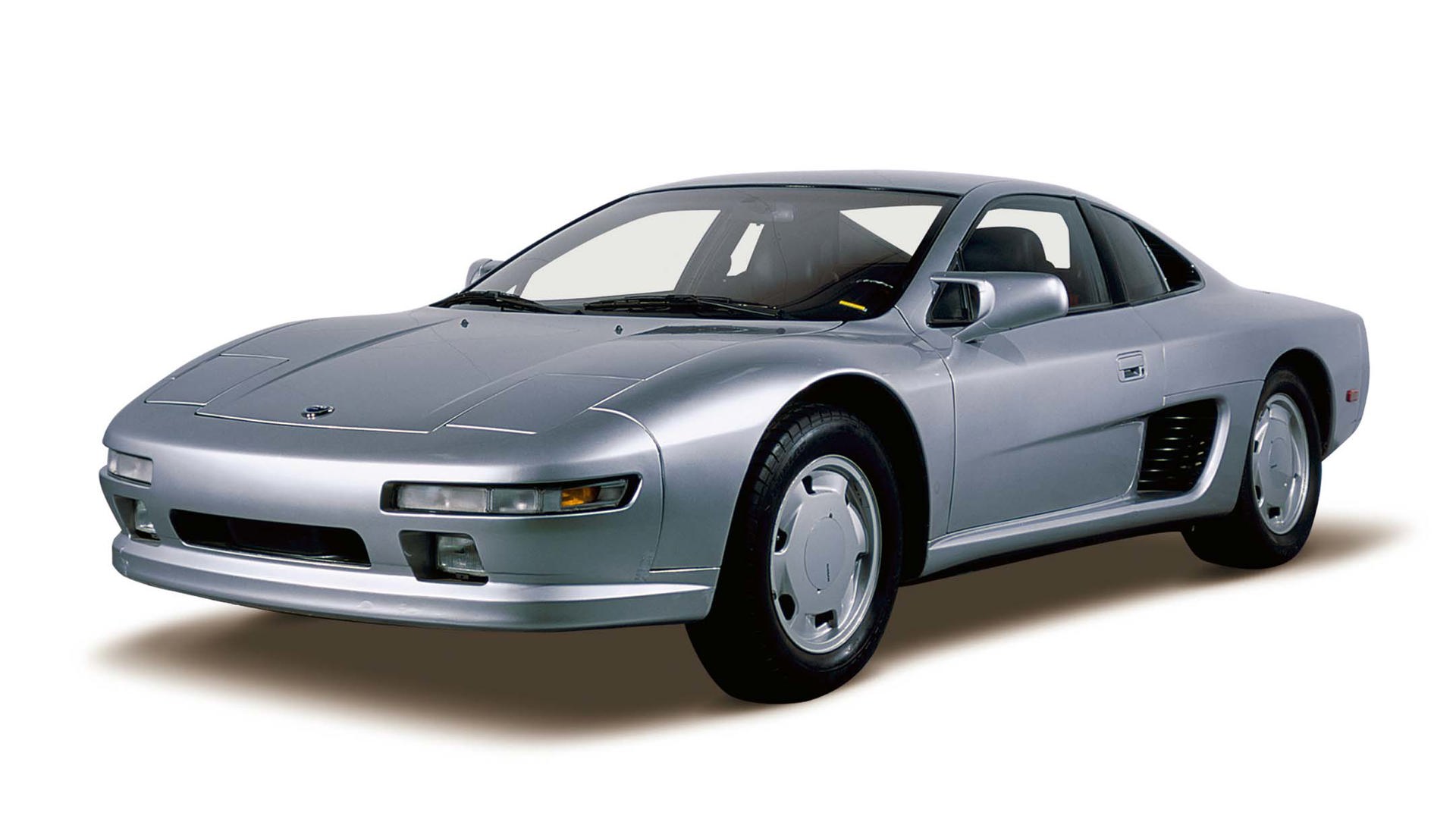

How they’ll be used helps determine how a concept car is built. Some have fully functioning chassis and can be driven, while others are empty shells that must be pushed into place on the showfloor. Some have full interiors, while those solely about exterior styling might not have doors that open. In 2001, Nissan showed the Z Concept, which toured the auto shows prior to the introduction of the 350Z. I got a ride in it on a very hot and sunny day, when I discovered its climate controls were fake – it had no ventilation system – and its windows didn’t open.

Like many concepts, the Z was built ahead of a planned production model. Very rarely does it go the other way, but that was the case with the Toyota FJ Cruiser. It was built strictly as a design study, set on a modified Land Cruiser chassis and with cues from Toyota’s original BJ and FJ models of the 1950s and 1960s. When it was shown at the Detroit Auto Show in 2003, it was so popular that the company’s executives greenlighted it, and it went on sale three years later, with almost no changes from the concept.

But around that time, many concept cars started to take a turn. In their earlier days they’d started as pencil sketches, hand-built and hand-modified through their development. But that made them very expensive to create, and automakers were starting to use sophisticated computer models to streamline the design process. Many concepts were very close to the production models, especially from the Japanese automakers, such as Honda’s SUT (which became the Ridgeline) and Model X Concept (which became the Element). Styling could be sent out to judge public perception with far fewer steps and a lot less money.

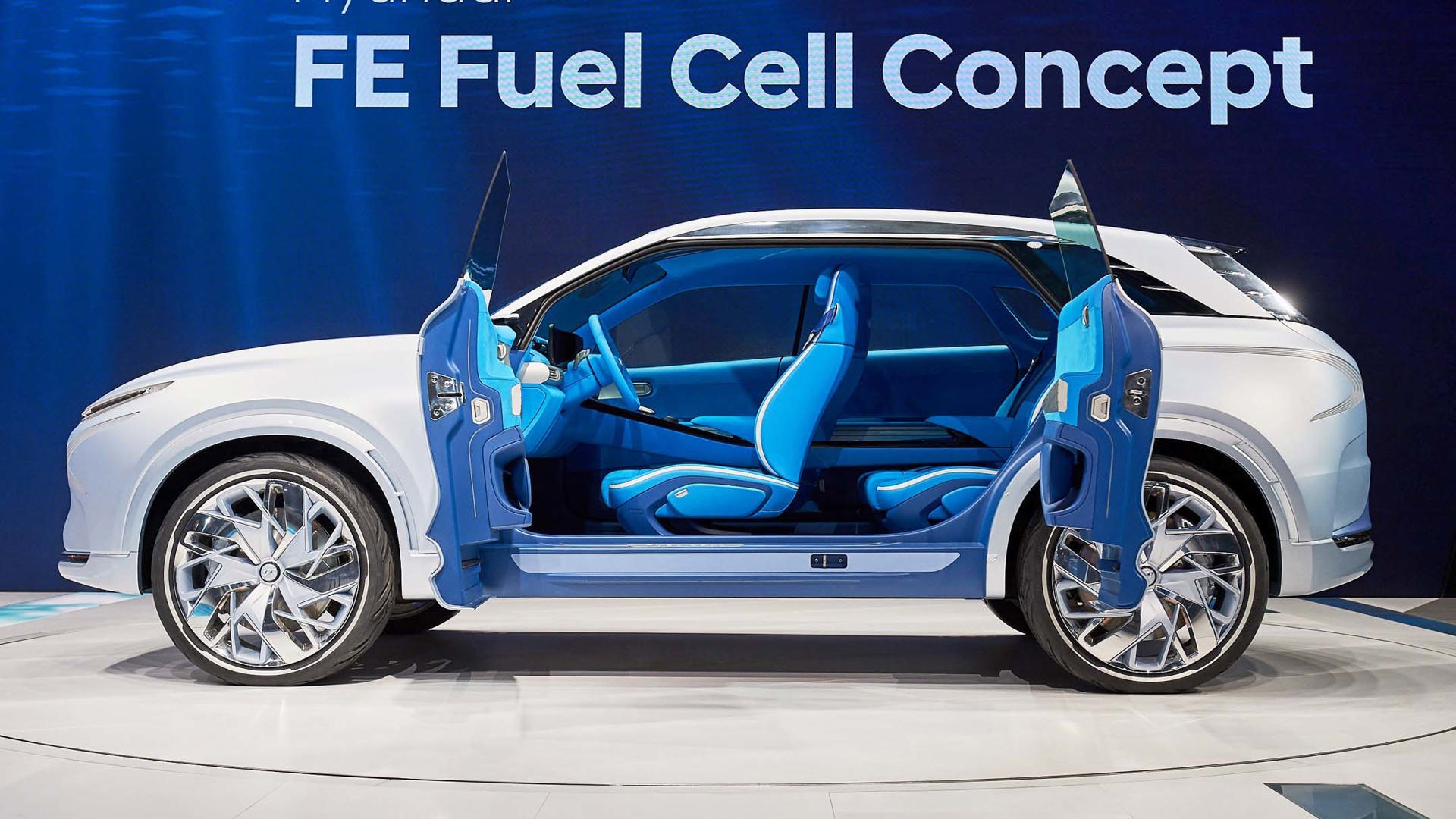

There aren’t as many over-the-top concept cars as there once were, but they’re still around. Today, they’re often as much about their inner technologies as they are about design. Many are testbeds for alternative powertrains and self-driving features, as automakers determine how they’ll work and how customers will react to them. Harley Earl was really on to something way back then.