Photos courtesy of Porsche

To the casual Porsche fan, the company’s new 911 Dakar might not make a lot of sense. Who wants a Porsche sports car that’s jacked up like a Subaru Outback? Surely you want your 911, Cayman, or Boxster to stick to the tarmac like a suction cup, low-slung and sleek. If you want something to handle a bit of off-roading or deep snow, then the Cayenne or the Macan are right there in the Porsche showroom. Who wants a 911 on stilts?

The clue’s right there in the name: Dakar. A gruelling desert endurance race, the Paris-Dakar of 1984 was a resounding victory for Porsche and helped the company further burnish its reputation as a builder of machines that are exotic yet tough and capable. This latest 911 variant is as much a part of Porsche history as are the Targa or Turbo models.

If you’re clued-in on trends in the classic air-cooled Porsche market, then the new Dakar model that was just unveiled will be no surprise whatsoever. Plenty of Porscheophiles have been making their own home-brewed off-road-capable 911s. The executives at Porsche are no fools and they’re unlikely to leave a market segment untapped. It’s why the new 911 Dakar practically had to be built. Here’s the long story of where it came from.

From Snows to the Serengeti

Porsche’s earliest motorsports efforts were mostly in European endurance racing. At the 1951 24 Hours of Le Mans, a specially prepared Porsche 356 successfully completed the entire race as Porsche’s sole entrant, coming in first in class. It was a big deal for a fledgling sports car company, even if the 356 SL in question does slightly resemble the Mutt Cutts van from Dumb and Dumber. I mean, just look at it.

By the 1960s, Porsche was an established name in racing, and it had a new car to take up the challenge: the iconic 911, released in September of 1964. Many 911s would, of course, participate in various circuit endurance races over the years, as they still do today. However, in the 1960s, one of the premiere racing events was the snowy and unpredictable Monte Carlo Rally.

Established more than a century ago, the Rallye Automobile de Monte-Carlo stands among the royalty of racing. The original format had contestants setting off from various places around Europe and converging on Monaco, where the winners would be fêted and much champagne would flow.

Before the trophies and the caviar, racers had to run a gauntlet called the Col di Turini, a wriggling mountain road comprised of 31 km of hairpin turns and race-ending rock walls. As if conditions weren’t treacherous enough, the locals developed a tradition of throwing snow on the road to catch the racers out. Very funny, guys.

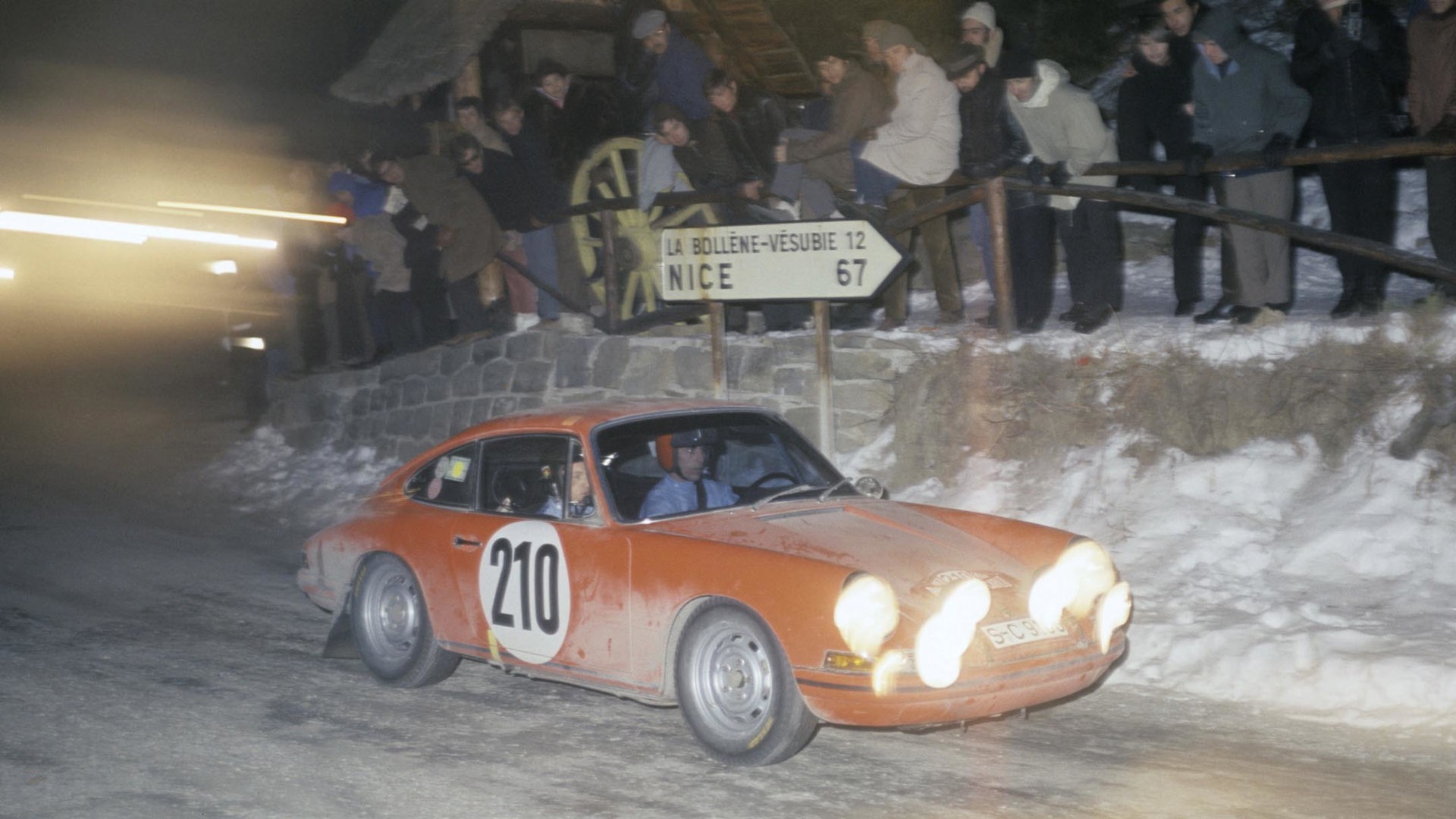

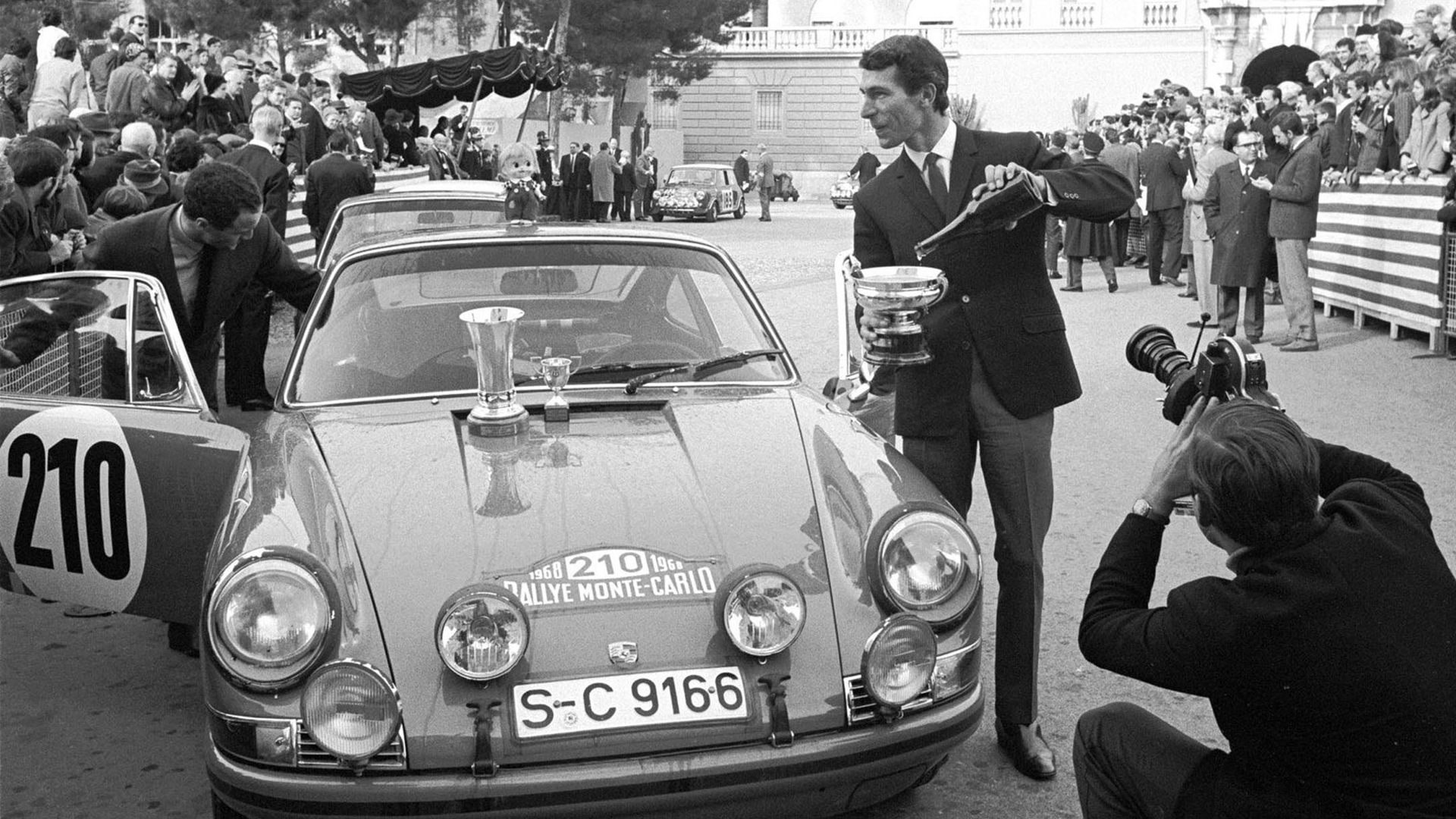

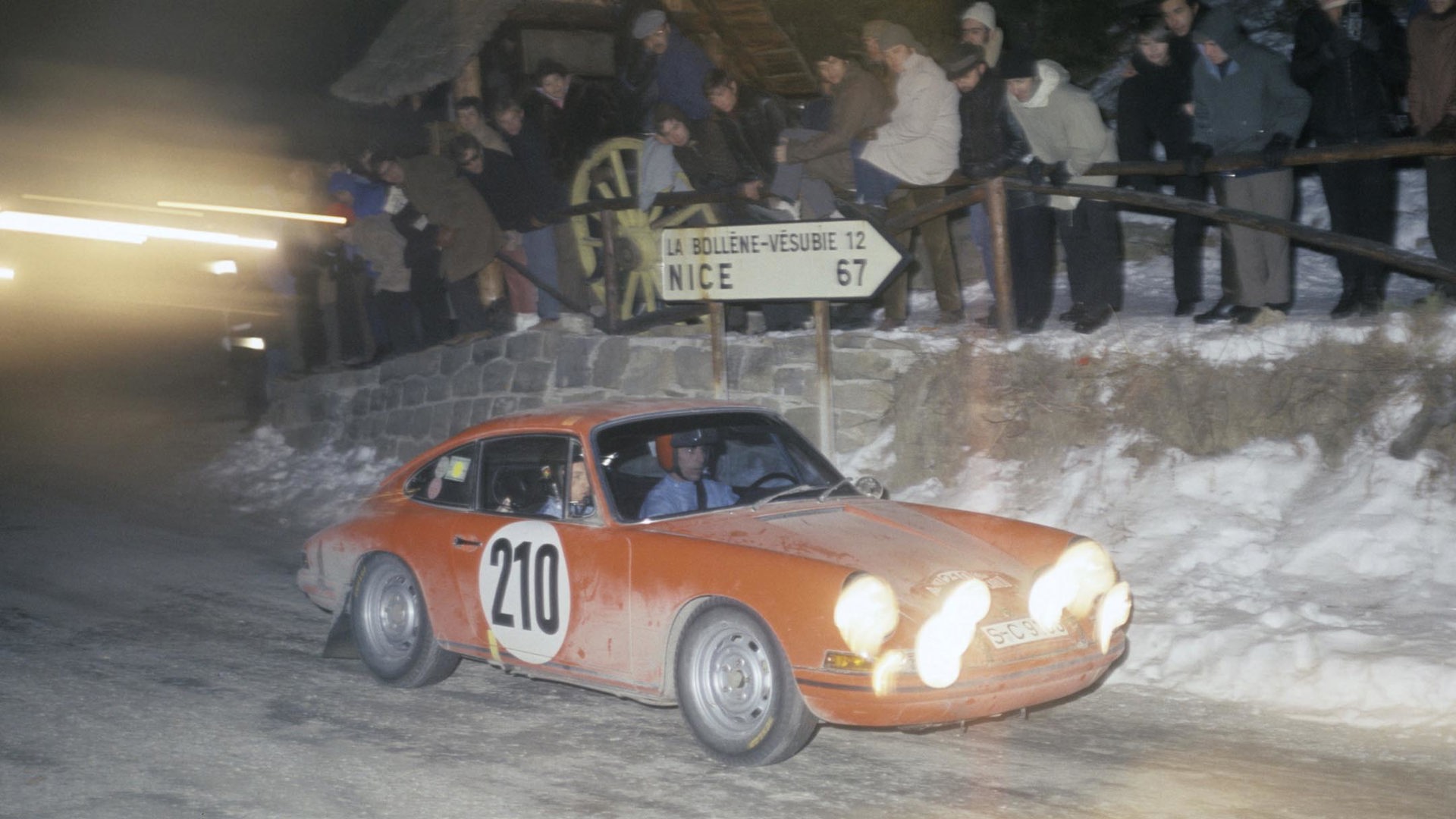

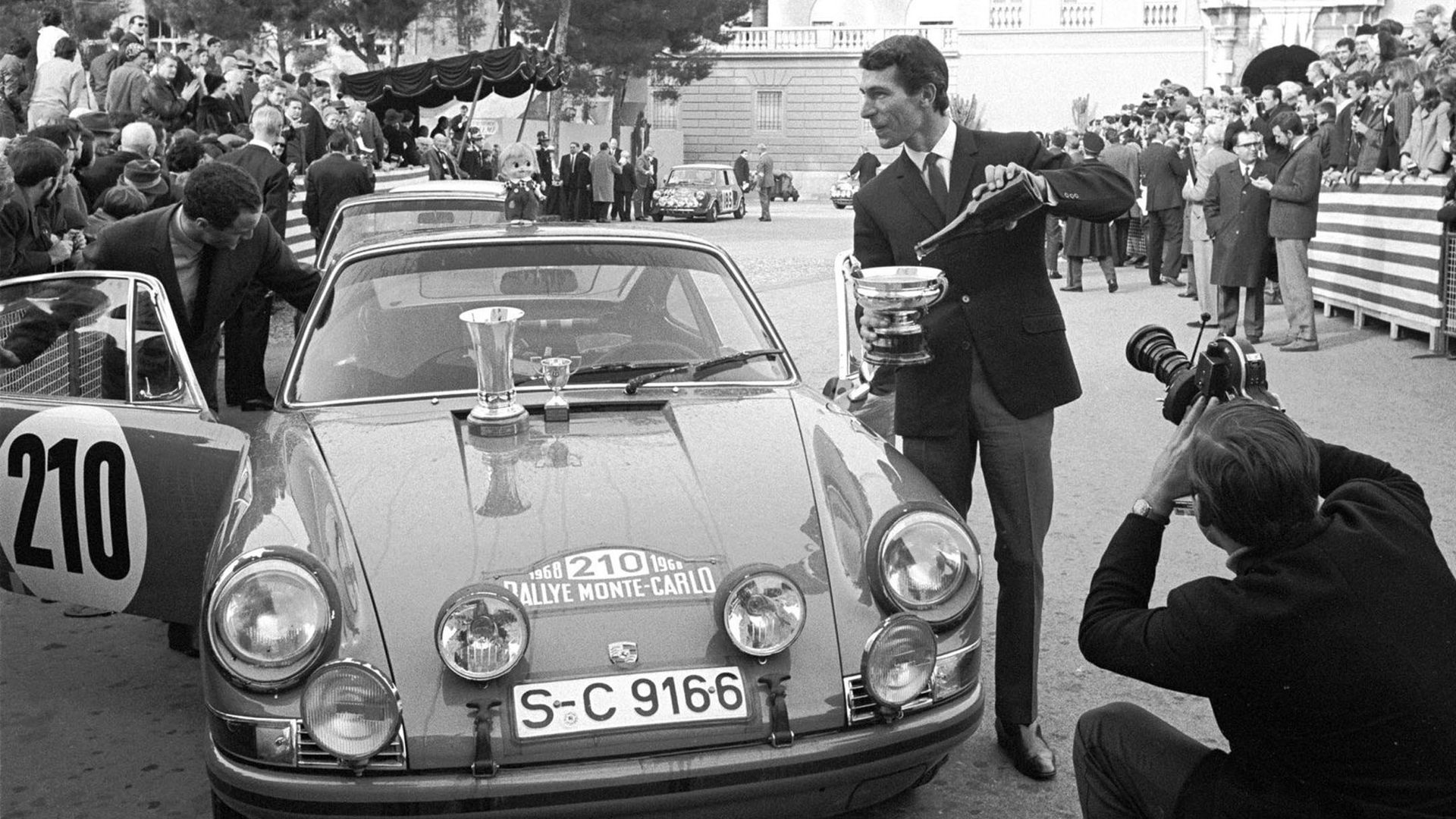

In 1968, English racing driver Victor “Quick Vic” Elford ran his factory-supported 911T to victory, outrunning the French Alpine team despite starting from behind. The 911T was relatively stock-looking except for auxiliary lights and mudflaps, but it was proof that a well-driven 911 could excel in the tough world of rally.

There followed a string of Monte Carlo wins by 911s, but Porsche’s next rallying efforts would take place far from the snows of the Alps. Instead of local pranksters with snow shovels, the 911 would now have to take on mud and heat and wandering wildebeest. In 1978, Porsche entered two specially modified 911s in the East Africa Safari Rally.

Bad Luck, Perseverance, and Some Famous Cigarettes

The most surprising modification made to the two 911s that Porsche sent to the Safari Rally was that they weren’t actually all that different from road car versions. The suspensions were lifted by 28 cm and plenty of underbody protection and extra lighting was fitted, but there was no all-wheel drive nor other cutting-edge tech. These were just 911s wearing hiking boots.

It wasn’t a new idea. At the beginning of the 1970s, Nissan had a great deal of success in the Safari Rally, fielding jacked-up Fairladys (similar to the Datsun 240Z in Canada), and showing that the rising Japanese auto industry was a force to be reckoned with. But the Safari Rally was unbelievably tough, with some 5,000 kilometres of rural African roads and all kinds of unexpected hazards.

Out of the gate, both Porsche teams were running strong, with one of the 911 SCs in first place. But then, during a deep water crossing, the lead 911 hit a submerged rock. With major damage to the rear axle, the team could only watch in chagrin as a Peugeot passed them. However, moral victory was preserved when both 911s limped across the finish line, coming second and fourth.

It was a good showing if not an outright victory, but Porsche’s rally efforts were more of a side project anyway. Endurance racing was still the main effort, and at Le Mans, the company’s Group C racing machines were proving to be nearly unbeatable. In 1982, English tobacco giant Rothman’s picked the Porsche 956 to be its rolling billboard, and Porsche promptly won two straight Le Mans victories.

Well, that worked. Sensing opportunities for further advertising success, Rothman’s teamed up again with Porsche for the 1984 911 SCRS program. Just 20 were made, each of them the same basic idea as the Safari Rally 911s, but with all of Porsche’s engineering know-how infused in. Despite being street-legal, the 911 SCRS was almost a full second quicker to 100 km/h than the standard 911 SC, and could take a beating on any rough roads.

It did very well in desert racing, just as both Porsche and Rothman’s had hoped. And it also formed the nucleus of an even bigger plan, one that would result in the creation of one of the greatest cars to ever emerge from Stuttgart.

The First All-Weather Supercar

Intended to race in a series that was killed off for being far too dangerous – Group B rallying – the Porsche 959 set the template for what the future of the 911 would look like. It was fast, with a 444-hp twin-turbocharged engine, it had all-wheel drive to get the power down no matter the conditions, and most versions even had an adjustable-height suspension. The 959 was both a technological powerhouse and one of the fastest cars on the road, period. So Porsche decided to see what it could do off the road.

The 1986 running of the Paris-Dakar rally wasn’t the first time the 959 competed, but it was the first time the car was fully resolved. The 2.85L flat-six engine was slightly detuned to 400 hp to better deal with low-octane fuel over the race, and the suspension and body protection was reinforced. Rothman’s would again be the racing livery of choice.

There’s a bit of an interesting footnote here, as it’s not like Porsche’s support team could also just tag along in a 911. Instead, the crew used Mercedes-Benz G-Wagens, but found the trucks simply too slow. So the factory swapped V8 engines into them, taken out of the Porsche 928. Up to this point, the G-Wagen hadn’t been available with a powerful V8, though it’s the default choice today. One of the Porsche team G-Wagens was so fast it technically finished the Paris-Dakar race in second place.

The shots of the 959 slewing through the sands in front of the pyramids has got to be one of the best photos in motorsports history. Porsche finished first, second, and sixth, and decided to rest on their laurels. The company wouldn’t go rally racing again.

But here, some 36 years later, the Dakar name is coming back to the 911 range. It’s had a long rest, but the heritage runs deep. And also, more importantly, this new model might just be the most fun version of all. Who wants a jacked up 911? The better question is who doesn’t want one?