Comparison Data

|

2018 Mini Cooper S E Countryman All4

|

2018 Mitsubishi Outlander PHEV

|

|---|---|

|

Engine Displacement

1.5L

|

2.0L

|

|

Engine Cylinders

3

|

4

|

|

Peak Horsepower

224 hp

|

197 hp

|

|

Peak Torque

284 lb-ft

|

281 lb-ft

|

|

Fuel Economy

8.4/8.8/8.6 L/100 km cty/hwy/cmb

|

9.4/9.0/9.2 L/100 km cty/hwy/cmb

|

|

Cargo Space

450 / 1,275 L seats down

|

861 / 2,208 L seats down

|

|

Base Price

$43,490

|

$49,998

|

|

A/C Tax

$100

|

$100

|

|

Destination Fee

$2,245

|

$1,450

|

|

Price as Tested

$50,785

|

$51,748

|

|

Optional Equipment

$4,950 – Essential Package $1,450; Style Package $650; Mini Yours Interior Style Piano Black Illuminated $250; LED Lights Package $1,400; Wired Navigation Package $1,200

|

$200 – Labrador Black $200

|

Photos by Stephanie Wallcraft and Michael Bettencourt

In most ways, these two cars couldn’t possibly be more different.

Crossovers and plugs haven’t always made for the most compatible combination. Higher ride heights and heavy all-wheel drive systems are exactly the sorts of features that electric vehicle designers typically avoid in the name of greater efficiency and range.

But Canadians continue to scoop up crossovers in droves, meaning that those same buyers have been forced to choose between the attributes they really want in their vehicles and the lower emissions and improved fuel economy that come with electric power.

Recently, that’s finally changed. Two unique and affordable plug-in hybrid crossovers have entered the market: the Mini Cooper S E Countryman and the Mitsubishi Outlander PHEV.

In most ways, these two cars couldn’t possibly be more different. But as the only two electrified crossovers available in Canada for a pre-incentive price under $55,000, the advantages and disadvantages of choosing one over the other are worth a closer look.

Combined power vs electric-only range

Not only are both of these vehicles plug-in hybrids, but both also come with standard all-wheel drive. As far as similarities go, though, that’s pretty much where they end. It’s clear from the outset that they’re built with different priorities.

The Mini Cooper S E Countryman combines a 65-kW electric motor with a 1.5L, three-cylinder turbocharged gas engine that’s paired with a six-speed automatic transmission. Together, they produce a total system output of 224 hp and 284 lb-ft of torque, 121 lb-ft of which is generated by the electric motor and therefore available from a standing start.

Three modes can be selected by the driver to dictate power use. In the default Auto eDrive setting, the car runs purely on electrons up to 80 km/h, at which point it hands things over to the combustion engine. Max eDrive mode works largely the same way except that gas takes over at 125 km/h, though we did find the engine would kick in unexpectedly in both of these modes. In Save Battery mode, the combustion engine does all the work while the starter generator charges the battery back up to 90 percent, where it’s held until called upon again. Manually selectable Eco and Sport modes are also present.

Regardless of mode, the combustion engine powers the front wheels while the electric motor drives the rears, with the dynamic stability control unit overseeing traction and kicking the second axle into motion as needed.

The Mini’s lithium-ion battery, which resides under the rear seats just forward of the motor, has a 7.6 kWh capacity and can be fully charged from a Level 2 charger in 2 h 15 min, and from a standard household plug in roughly 3 h 15 min. Though it’s rated with almost double the range in some parts of the world, Natural Resources Canada has assessed its electric-only driving range at a relatively low 19 km. (This difference is normal as NRCan factors things we use more often in Canada, like heating systems, into their testing procedures.)

Michael Bettencourt, autoTRADER.ca’s Managing Editor, joined me in this head-to-head comparison, and he questions whether this range is too low to be of value during Canadian winters.

“A full charge with the heat on gave me nine kilometres’ worth of indicated all-electric range,” he says. “At that point, you have to ask how many owners in winter would actually bother to plug it in.”

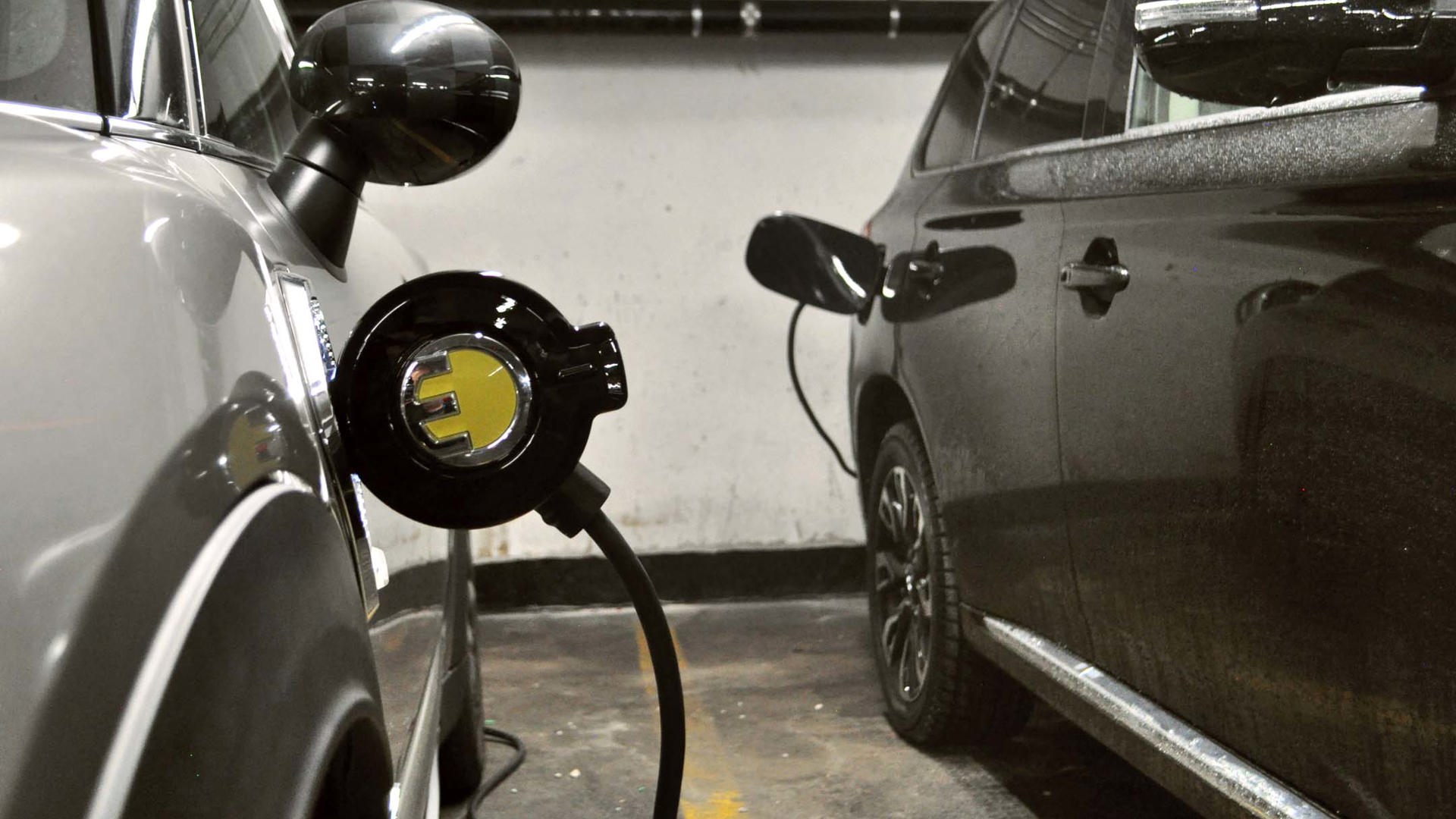

He also points out that owning the Mini requires signing up for a breach in EV etiquette.

“Annoyingly, you have to unlock the Mini before you can unplug it – which not only means lots of fruitless tugs at the charger, but also that other EV folks who see or know that you’re full can’t unplug you and plug themselves in, as is courteous EV tradition.”

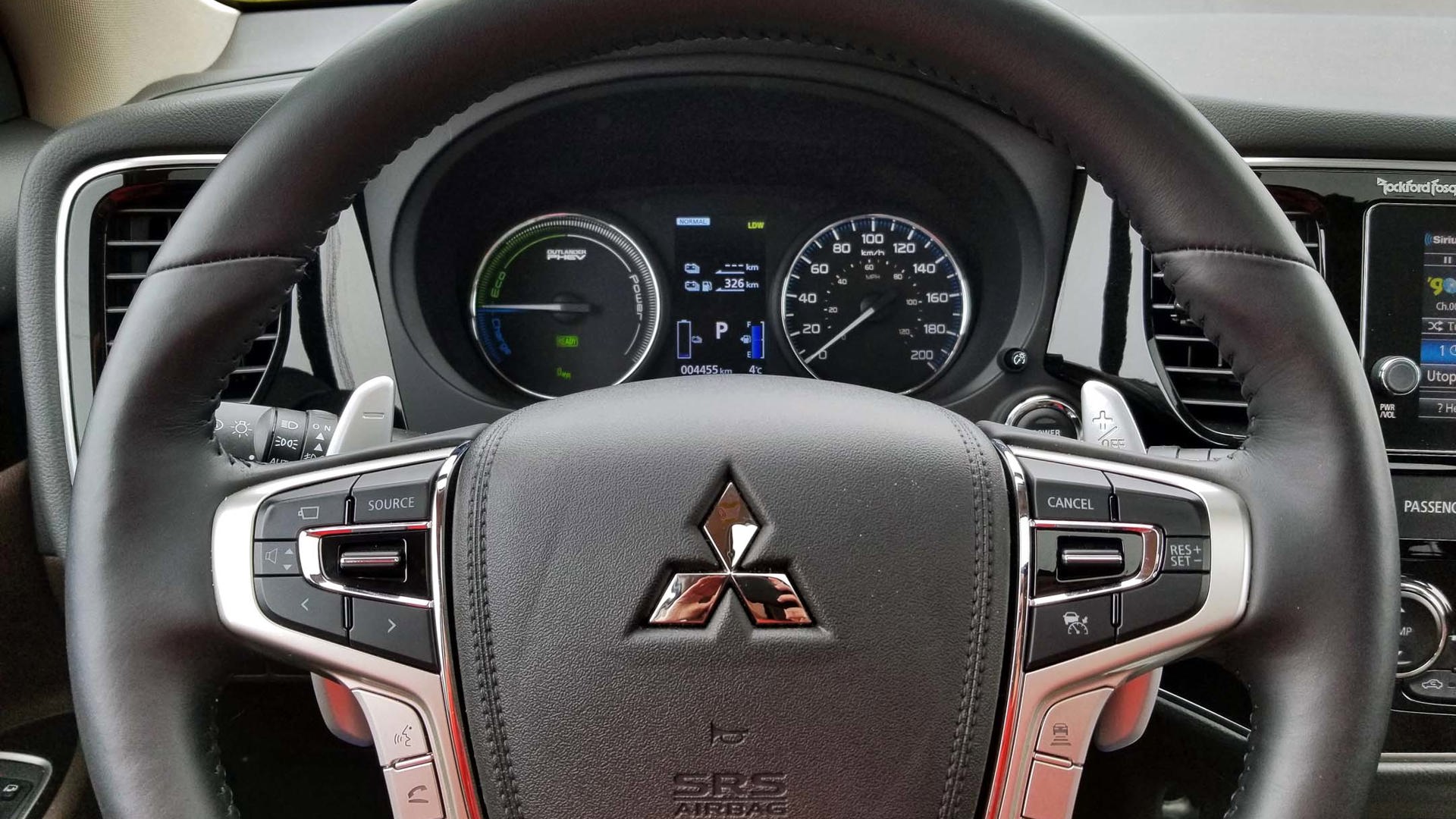

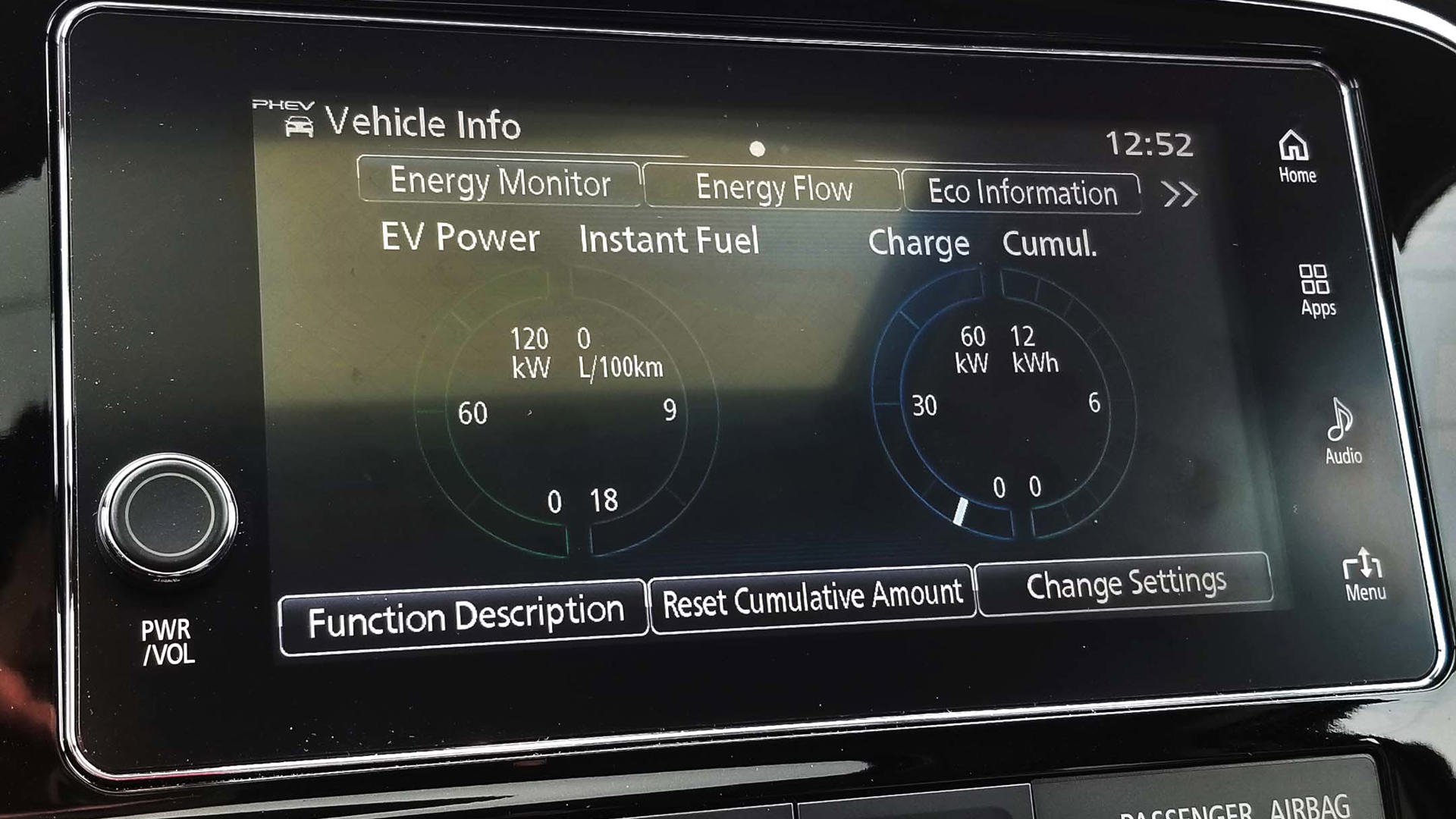

In the Mitsubishi Outlander PHEV, two 60 kW motors are integrated, one on each axle, along with a 2.0-litre, four-cylinder gasoline engine with variable valve timing matched to a continuously variable transmission. Here, total system output amounts to 197 hp, and while Mitsubishi has thus far declined to publish an official torque figure – a number reflecting all three power sources would be inaccurate as they’re never all running at the same time – combining the gas engine’s torque with that of the rear electric motor nets 281 lb-ft, which is as good an estimate as any.

The Outlander does some efficiency control on its own through three drive modes. In EV Drive Mode, power comes exclusively from the electric motors. When the battery is low or there’s a burst of acceleration, Series Hybrid Mode kicks in and delivers additional power to the electric motors, using the gas engine to complement the battery while also supplying some recharge. In Parallel Hybrid Mode, which kicks in at high and/or steady cruising speeds, the gas engine drives the front wheels with the electric motors kicking in when needed, such as on uphill climbs – any excess power from the gas engine is fed back into the battery pack.

On top of that, the driver can select from four power use modes: Battery Save to conserve charge on highway drives; Battery Charge to run exclusively on the combustion engine and actively recharge the battery; EV Priority mode to keep the gas engine permanently deactivated (given sufficient battery charge and no sudden stabs at the throttle); and Eco mode for increased overall efficiency.

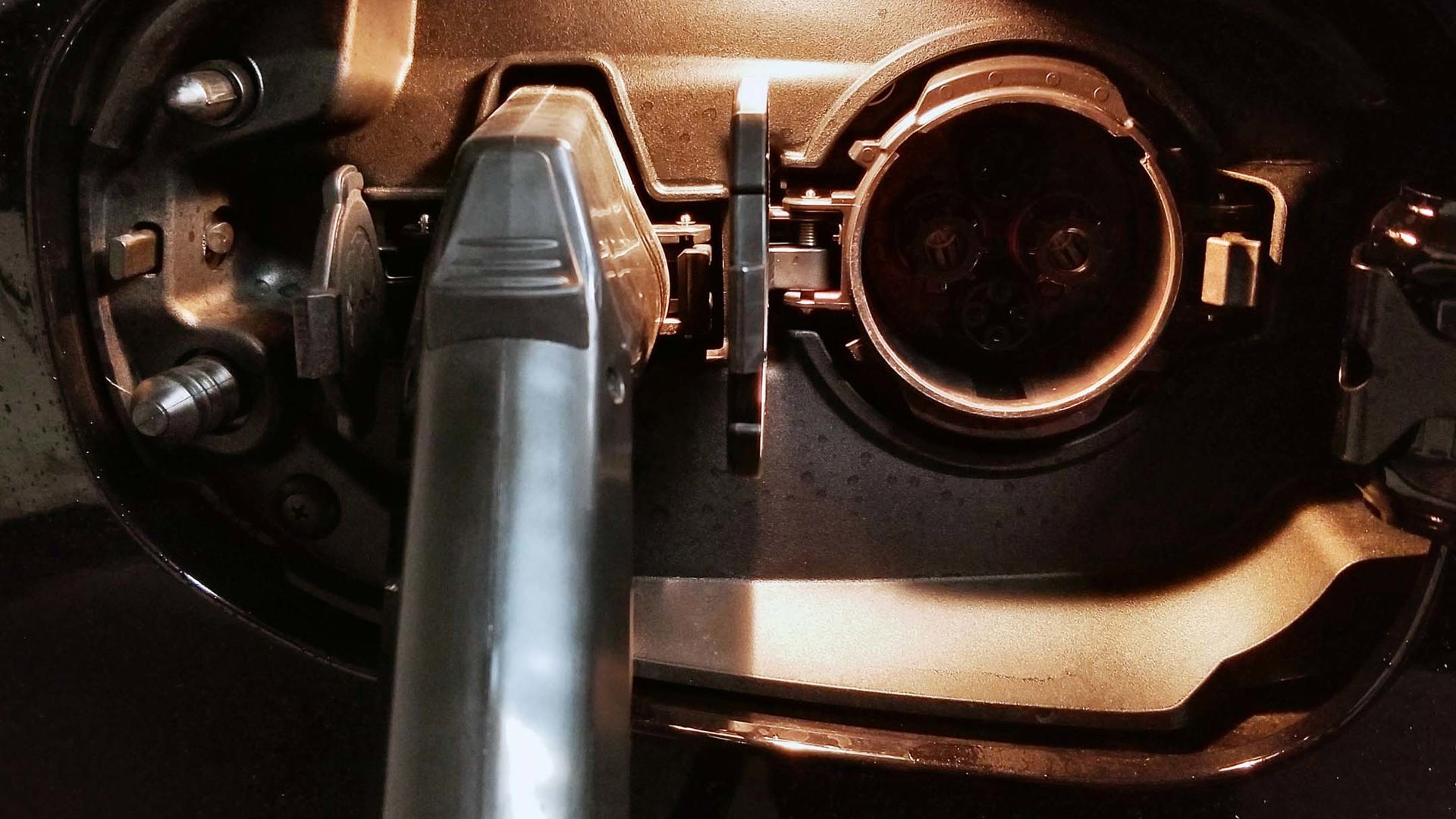

On the battery side, the Outlander’s is also lithium-ion and has a capacity of 12kWh. It’s positioned between the front and rear axles and doesn’t intrude into the passenger compartment. What really makes the Outlander’s charging stand out, though, is that it’s the only PHEV on the market with Level 3 DC quick-charging capability.

“A CHAdeMO charger can give you an 80 percent charge in roughly half an hour, which is great for those ‘zip and goes’ at the mall,” Bettencourt says.

With a Level 2 charger, the Outlander receives a full charge in under four hours; at a regular 120-volt household plug, it takes roughly eight hours.

In terms of handover between the combustion and electric engines, both cars are equally smooth and unobtrusive. But the Outlander clearly comes out ahead on outright range, and it also wins on rechargeability.

When Bettencourt and I took these two vehicles for a spin, we found that much of the Mini’s electric power had already been used up by the time he got it to the meeting point just a few kilometres away, and it didn’t take us long to drain the rest. Despite being in Save Battery mode for much of our drive, once the battery flatlined, it never recovered. Its EV power only came on briefly on restarts from that point on, until we plugged it back in.

By contrast, the Outlander not only gave us more EV power to work with from the start, but it didn’t take much effort at all to earn back some charge in city driving. While the steering-wheel-mounted paddles shift gears in a gas-powered Outlander, in the PHEV they shift between five different degrees of regenerative braking – the very feature I recently suggested would be helpful on the new Nissan Leaf. While B1 is so soft as to be almost unnoticeable, B5 makes the brakes nice and grabby – I think I could have even gone for a B6 and not found it overly aggressive – and created an easy-to-spot and very satisfying recharge that extended our range for several kilometres over our half-day of driving.

When you consider both vehicles running in gas-only mode, though, the Mini does better, averaging an official 8.6 L/100 km combined versus the 9.2 L of the Outlander.

Drive experience swings in Mini’s favour

Again, where drive feel and experience is concerned, these two cars couldn’t be more different. And this is where things swing back in the Mini’s favour.

The Outlander PHEV may be new to North America, but it has been available in other markets for quite some time, and is built on a platform that has been in use since the 2013 model year. In its gas-only setup it has an optional third row, and while it can only be bought with two rows as a PHEV, it still drives like the somewhat-outdated, mid-size SUV that it is: it’s heavy at 1,895 kg (4,178 lb), bulky, and not especially nimble. The steering is relaxed, handling is uninspiring, and while it has enough power to haul its own weight around, throttle response isn’t especially peppy.

The Mini, though, is an entirely different creature. The three-cylinder engine is a touch rough and noisy, but power delivery is energetic, and it boots around town with that go-kart-like zippy handling that’s always been one of Mini’s selling points. If it’s a Mini you’re after, you’re not sacrificing much here to add in a plug. (As previously mentioned, though, you’re not getting a whole lot of EV driving back, either.)

Rearward visibility isn’t stupendous in either of these vehicles, with large rear head restraints in both – particularly evident in the Mini.

“Visibility is noticeably compromised in the Mini, with massive rear head restraints that have to be removed to see anything out the tiny rear window,” Bettencourt says.

Twins to gas-only siblings on the outside, Mini shines brighter inside

Neither of these cars looks dramatically different from its gas-powered sibling, which is positive.

Apart from unique PHEV badging, the Outlander could be mistaken for any other on the lot. That means that it brings along with it some conservative styling. The dynamic shield grille stands out in a crowd, but it’s otherwise a very typical-looking SUV. On this GT unit, the leather seats with contrast stitching are nicely finished and reasonably comfortable, but the resulting three-tone to my eye looks overdone. Of course, black-on-black is always an option.

The Mini is only slightly more overt, sporting plug-shaped badges on each flank highlighted with the brand’s signature electric yellow. Inside, it continues to be Mini through and through with circular gauges, great seats, and high-quality finishes.

“Amazingly artistic and modern interior compared to the Mitsubishi, especially with the LEDs surrounding the massive circular instrument panel,” Bettencourt notes.

For those looking to pick up a plug-in hybrid that’s affordable but still feels luxurious inside, the Mini Cooper S E Countryman All4 is about as good as it gets.

Advantage Outlander for space and storage

Mitsubishi’s under-floor battery doesn’t encroach into the cabin at all, which means that the Outlander PHEV loses very little in the way of roominess. The second row is downright spacious, and cabin storage is not exceptional but certainly acceptable. Where the Outlander blows away anything even remotely comparable is in rearward cargo storage, where it fits a whopping 861 litres with the rear seats upright and 2,208 litres with them down.

There’s some vestigial paraphernalia in there like cup holders intended for third-row users that PHEV owners will never touch, and the second-row seats don’t lie especially flat, but this is still far and away the least you’ll pay for a plug-in hybrid with this much cargo space – unless you dig minivans, in which case the Chrysler Pacifica Hybrid comes into contention. But that’s another discussion.

For the Mini’s part, the battery and electric motor have taken up more of its space. The second row would work for young kids, but it may be too tight a squeeze for some adults to want to use it regularly.

“A particularly rearward position (on the front seat) barely allows enough room between the rear seat and seatback for my foot, never mind knees, though it becomes easier with the front seat adjusted for more-typical-height folks,” Bettencourt says.

A smaller interior means smaller compartments for storage. And in the cargo area, there’s 450 litres of space behind the second row and 1,275 litres behind the first – that’s 45 and 115 litres lower than the gas-powered Countryman. Those are not terrible figures next to a car, but they are lower than average for a crossover.

Infotainment and connectivity closer, but Mini has the edge

The Mini is set up better for drivers who like to stay connected – provided they’re Apple owners. It has an available wireless charging pad, but it’s built into the armrest and may not be long enough for some larger phones. The infotainment system has Apple CarPlay functionality but not Android Auto. It is clearly and attractively laid out, though, and our test unit has built-in navigation, which the Outlander does not.

This difference sparked an animated discussion. I argue that if a car has Apple CarPlay or Android Auto included, then paying to have navigation included as well – it’s part of a $1,200 option package in the Countryman that also includes that wireless charging pad and Mini Connected XL – is a waste of money since Google Maps is almost always better than the on-board systems anyway. Bettencourt counters that phone apps rely on using data, maps don’t stream to the Outlander’s screen if you don’t use the cable, and you could end up stranded with no directions if you wind up in an area with no coverage, or if your phone dies.

I’d rather spend my $1,200 on my already-robust data plan and rely on USB charging, but to each their own.

Other features and government incentives a stalemate

Our Countryman tester had several packages installed that integrate some desirable features. On top of the Wired Navigation Package detailed above, the Essentials Package ($1,450) adds a panoramic sunroof, heated front seats, a centre armrest in the second row, and front fog lights; the Style Package ($650) bolts on chrome exterior and interior accents, interior accent lighting, and a leather steering wheel; the LED Lights Package ($1,400) integrates LED adaptive headlights and fog lights. It also has 18-inch wheels, a power liftgate with a lock button, adaptive cruise control, and memory seats.

Blind-spot monitoring is not equipped and appears not to be available at all, and the same goes for a heated steering wheel, both of which are surprising omissions.

The Outlander GT PHEV is configured for all-in pricing with heated front seats (but with no memory feature) and a heated steering wheel, a standard-sized sunroof, Android Auto and Apple CarPlay functionality, a power liftgate, and a suite of safety features that includes blind-spot monitoring, rear cross-traffic alert, lane-departure warning, forward collision mitigation with pedestrian detection, and adaptive cruise control. It also comes with Mitsubishi Motors Canada’s 10-year, 160,000 km warranty, which here extends to the battery and other powertrain elements, plus 10 years of roadside assistance. That’s very difficult to ignore.

The MSRP on the Countryman, including freight, comes in at $50,785. For the Outlander, the sticker price is $51,748. In Ontario, both cars qualify for a rebate of $7,000, while you’ll receive up to $4,000 back in Quebec and up to $2,500 in British Columbia.

“This $7K is a hefty discount,” Bettencourt says. “It’s hard to believe, though, that the Outlander’s useful 35 km of official range receives as much of a rebate as the Mini’s relatively paltry best-case-scenario 19 km range.”

The Verdict

On paper, delineating which of these cars is best for which type of driver is quite easy. If you want an electric-centric, highly practical crossover, then the Mitsubishi Outlander PHEV is for you. If style and driving enjoyment are higher priorities, go with the Mini Cooper S E Countryman All4.

As for making a personal recommendation, I’ve struggled with this mightily. On the one hand, I am more than happy to embrace my conservative nature, and the Outlander appeals to that in every possible way. But on the other hand, I was horrified to realize that I actually care quite a lot about what my neighbours think of my family and our style choices. The Mini might be a hipster with a man bun, but at least it’s not a grandpa in a cardigan.

In the end, when I weigh what would matter to me and my family most – driving enjoyment is a key factor, and a smaller vehicle serves our urban lifestyle better than a large one, even when factoring in the dramatic loss in cargo space – the Mini would be my choice, but only by a hair. And if I ever had any large service bills on it out of warranty, I’d forever kick myself for choosing fashion over function.

Bettencourt’s conclusion was the exact opposite.

“Value-wise, the Mini is just too small in too many areas – interior space, cargo space, all-electric range – to make up for its not-too-small price,” he says. “In my mind, it’s all sizzle, no steak, especially if you truly want to run as much as possible in silent, all-electric mode.

“The Outlander PHEV is the brilliant but somewhat geeky scientist that’s a little socially awkward, but surprisingly capable at a wide number of tasks. Though I love the Mini’s interior and funkier overall nature, its lack of room and range would push me to the Mitsu’s more square but solid family value.”