Pre-conditioning is one of the best features of electric vehicles (EVs) and plug-in hybrids, but it’s not often talked about, so many Canadian drivers are not aware of all the benefits it offers during our harsh winters. What is pre-conditioning, how does it work, and how do you use it? You’ll find those answers here along with how it can make you more comfortable and save you money every day.

What is Pre-Conditioning?

Remote starters for cars have been around since the 1980s, even if they still haven’t replaced the time-honoured Canadian ritual of brushing off the driver door, chipping away the ice, starting your car, and then going back into the house for half an hour while everything warms up.

By the way, letting your engine idle for 20 minutes while you sip your coffee at the kitchen table seems like a great idea, but it doesn’t work all that well. As modern engines get more and more efficient, this method becomes less effective every year. Some modern cars can sit and idle in sub-zero temperatures all day long and still not move the temperature needle on the instrument cluster, all while burning gas the entire time. This isn’t good for the car, either, since while the oil in the engine might be warm, the oil in the transmission, steering, and differential are all still ice-cold when you start driving.

For electric vehicles, pre-conditioning, also called preheating, uses electricity from the power grid to let you warm up the cabin while it’s still plugged in. Like using a remote starter, this will result in a car that’s warm and toasty before you get in and drive – but without impacting battery charge and thereby electric range, which often suffers if climate control is being used.

Electric vehicles don’t rely on waste heat from an internal combustion engine (ICE) like a gas or diesel vehicle, both of which take cabin heat from the engine’s cooling system. This is why ICE vehicles take so long to get warm – you’re waiting for litres of fluid to get hot before the air is warm enough to heat the cabin. Instead, EVs use one of two common ways to get heat: a heat pump, which works like the heat pump in a home, or an electric grid heater, which acts like a hairdryer to push out warm air. EVs are also likely to have heated seats and a heated steering wheel because they warm you up directly instead of having to warm up all of the air in the cabin and using them has a far smaller impact on range.

Both of those types of heaters use electricity, so they’re just as happy to take it straight from the wall as they are the battery, which is where pre-conditioning comes into play. Nearly all modern EVs and PHEVs will let you use either an app built into the infotainment system or one on your smartphone to tell the EV or PHEV when you plan on leaving, so you can set a schedule for when you want the preheating to begin.

If your car knows you’ll be headed out at 7:30 a.m. every weekday morning, you can program it to prepare. That has benefits for charging and range (a warm battery is more efficient than a cold one), but this is about keeping your backside warm, so we’ll stay on track. The vehicle will automatically activate the heater, heat pump, or heater grid; and warm up the cabin so it’s ready for your commute. If you’re leaving at an unusual time (thanks to working from home or just life being life), you can use the same app or your key fob to turn the feature on or off any time you want.

Pre-Conditioning Put to the Test

With the help of a 2021 Toyota RAV4 Prime PHEV (which uses a heat pump), we tested pre-heating for effectiveness, energy use, and the amount of comfort it provided, then compared it with a gas-powered car to see how much more pleasant a pre-conditioned vehicle could be. Keep in mind that this wasn’t a scientific test and there were a lot of different variables at play that could have affected the results.

It wasn’t the coldest week of the year for our testing, but it was consistent. Three tests were completed: one with me telling the RAV4 when I would be leaving and having it warmed and ready to go; one not pre-warmed but using only electric-powered heat; and one using the defroster for the first portion of the trip until the front glass had cleared and the engine could be shut back off.

For each test, the climate control was set to 21.5 degrees and the seat heater and steering wheel heater were used for the duration. While the average speed was slightly different for each test – related to time spent “idling”, waiting for the vehicle to warm – the drive itself was as identical as possible with no traffic, stoplights, or time waiting at stop signs.

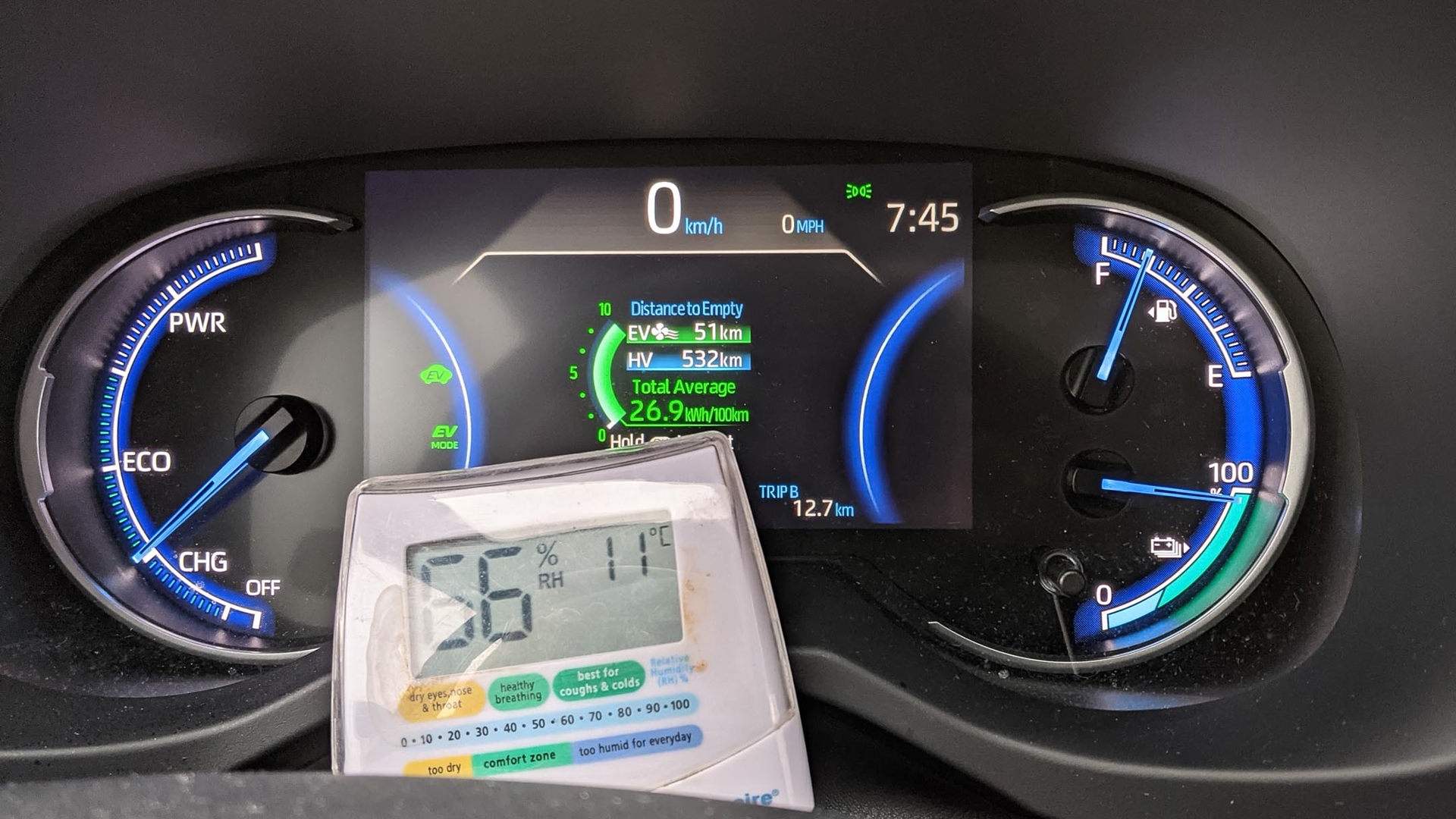

On the first pre-warming test, on a zero-degree morning, I came out to an 11-degree cabin and warm seats. While that doesn’t seem particularly warm, further testing in the RAV4 and other vehicles showed it to be quite a comfortable starting temperature.

About 27 minutes and 25.1 km later, I had used 28 km of indicated range, driven 100 per cent of the time in EV mode, and the dash showed I had used 25.9 kWh/100 km. For reference, the RAV4 Prime has an official rating of 22.3 kWh/100 km. The trip itself, by those figures, used 6.5 kWh of electricity which, using my local energy rates, means the trip cost $1.04. I haven’t included pre-heating power in the figure, but we’ll come back to that.

Day 2 saw me leave the house to a chilly zero-degree cabin. The same 25.1 km drive used an indicated 32 km of range and 30.1 kWh/100 km. That means it cost $1.32 for the same trip (7.6 kWh). No, it isn’t a large cost difference, but it is 17 per cent more electricity use. More importantly, I was warm the entire drive.

Day 3, I used the vehicle’s front defroster, which meant more time idling waiting for clear windows, though I was able to put it back into EV mode at 7 minutes and 3 km, at a point in the drive where the RAV4’s display showed 34.6 kWh/100 km, giving you an idea of how much electricity is used in initial warming even with the gas engine on. The end of the drive showed electricity use of 27.6 kW/100 km and the EV driving ratio fell to 75 per cent and an indicated 1.7 L/100 km. So, the RAV4 Prime used 6.9 kWh and $1.10 in electricity and an estimated (using Natural Resources Canada figures) 0.52 L of fuel. Using a gas price of $1.20/L, that’s $0.62 for a total drive cost of $1.72.

The Cost of Pre-Conditioning

To recap, the pre-heated drive cost 21 per cent less than the cold EV drive and 39 per cent less than the drive using the gas engine. More importantly, I was warm and cozy the entire time. The pre-heated drive would also have offered more than 10 per cent more electric range than the non-heated drive. Pre-warming was cheaper, cleaner, and more comfortable, and while I wasn’t able to make an identical test drive on the day, the RAV4 Prime’s pre-heating did warm the crossover on a −10 degree morning, parked outside.

How much would a gas-only vehicle cost to do the same trip? Based on the 25.1 km distance, the same amount of idling time, and a gas-powered RAV4’s 8.4 L/100 km combined rating, along with estimates on cold-weather impact from NRCan, a gas-only crossover would have required 3.0 L of fuel, for a cost of $3.60.

But how much energy does pre-conditioning use and how much does it cost? The way most of these systems work is they also schedule the battery to finish charging at the same time you planned to leave, meaning you’re leaving with a warm battery, further boosting range because a warm battery is a more efficient battery. So just looking at your power meter won’t help with the calculation. Instead, I waited for the vehicle to be fully charged using the “charge now” option and turned on the “remote start” preheat option. The charge plug at the wall re-engaged and I counted power meter revolutions. There wasn’t an observable change in speed compared with the RAV4 Prime not drawing energy from the wall.

That means we’re going to have to do an estimate. The RAV4, even after manually pre-conditioning for an hour (far longer than needed, but used as part of the experiment), showed a full battery charge, meaning it can’t be using more power than the vehicle can get from the wall cord, which is 12 amps or around 1.4 kW. Run the RAV4 Prime’s pre-conditioning for the 20 minutes it took to actually warm up in the first test, and you’re using 0.46 kWh, for a cost of 7 cents. Even the full hour would have been only 22 cents, which leaves it still cheaper than getting in and going, as well as more comfortable.

While we used just one province’s electricity cost for our calculations, more expensive electricity won’t close the gap between the three different test cycles, and electricity would need to be 55 cents per kWh to equal the cost of gas. When it comes to emissions, a 2017 Natural Resources Canada report put electricity CO2 per kWh ranging from just 1.2 grams in Quebec to as high as 790 in Alberta, though most of the country’s population is in areas with 40 grams or less. Using Ontario’s 40 g/kWh, the EV emits 278 g of CO2 including 20 minutes of preheating on our test loop. With the gas vehicle, it was approximately 6,900 grams (6.9 kg) of CO2 in the same drive. Even using the worst CO2 per kWh figure, the EV emits just 5,498 kg of carbon dioxide.

With plug-in hybrid vehicles, this pre-heating comes with another benefit. In many PHEVs, when the outside temperature is cold enough and you activate the heat, the engine will turn on. This is especially true if you turn on the front defroster, which in this RAV4 Prime, means the engine will stay on for as long as it takes to clear your front glass. In winter, that can be a long time. Turning on the engine and running it for short periods like this is harmful in the long term because the engine doesn’t get to reach operating temperature. It uses more fuel to boot since gas engines run extra rich (injecting more fuel than necessary) to warm up the engine and emissions control devices. If the cabin is already heated and the glass defogged, you can avoid using the internal combustion engine and keep your PHEV in EV mode for longer. Of course, this all works in the summer, too, when you can cool your vehicle off before you get in, an exercise taking even less time.

Pre-conditioning or pre-heating your EV or PHEV can save you money and slash emissions while raising your level of comfort and usable range. It’s another cool EV trick that’ll keep you hot on a winter morning.