Sold at the Bonhams auction in Monterey, California, the first-ever McLaren F1 imported into the US fetched an eye-watering US$14.2M. Add in a 10 percent buyer’s fee, and the cheque required is US$15.62M. That kind of money could buy you a yacht, or a jet aircraft, or a small detached single-family home in Vancouver.

As with so many classic cars, the time to have bought an F1 was years ago, when they were worth the paltry sum of millions of dollars. In fact, unlike the craze for old Ferraris or air-cooled Porsches, the F1 has never been affordable. It’s entirely possible that this silver shard of automotive excellence will eventually go on to supplant the Ferrari 250GTO as the most-expensive cars ever.

Even Elon Musk, purveyor of an exclusively electric future, has a McLaren F1. When somebody who owns their own rocket company and electric-vehicle hype factory dreams about an internal combustion car, you know it’s something pretty special.

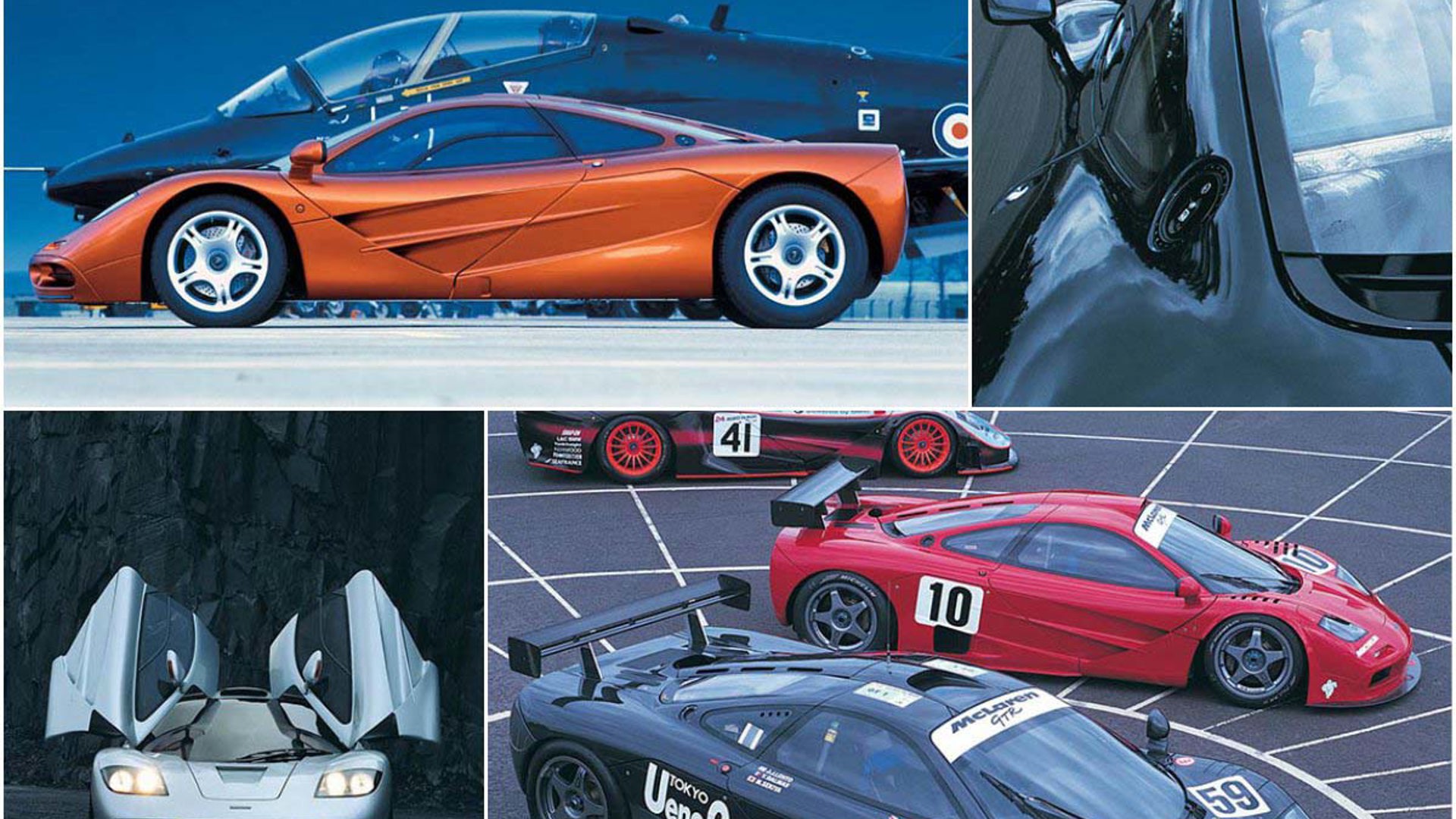

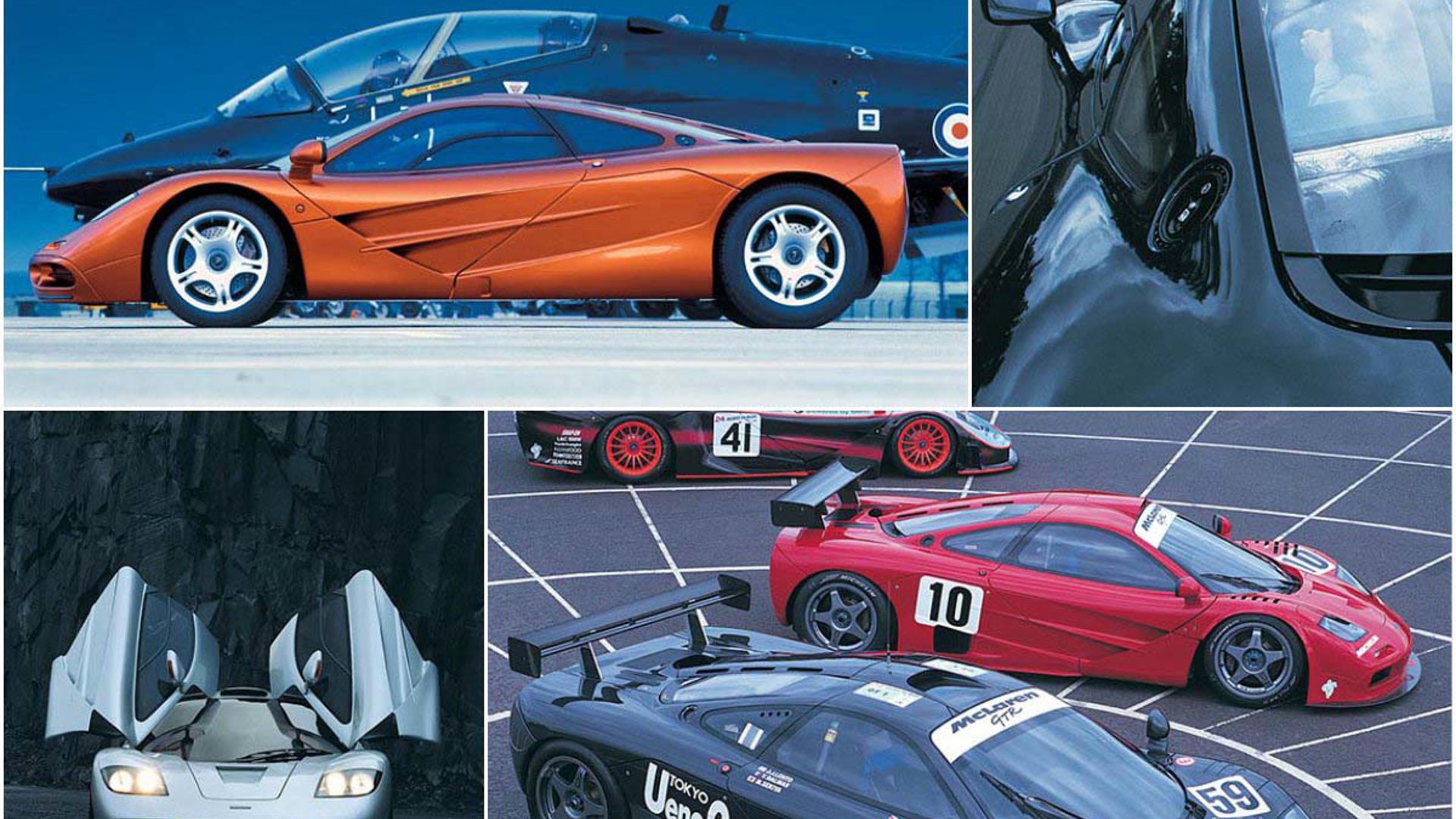

For many people, the McLaren F1 will never be surpassed. Unlike 1980s heroes like the Porsche 959 and Ferrari F40, it was produced in ridiculously small quantities (just sixty-four road-going examples, 106 including prototypes and racing versions), and it was astronomically priced from the outset. The roughly contemporary Jaguar XJ220 was a bargain by comparison.

However, if you wanted the best, the F1 was it.

In 1988, McLaren was coming off the back of their triumphant F1 championship effort. The rivalry between Ayrton Senna and Alain Prost got the headlines, but the Honda-powered McLaren MP4/4 didn’t care which side you chose. Over the sixteen Grands Prix, the McLaren chassis won 15 outright.

At the airport, waiting for a flight back from Milan after winning the Italian Grand Prix, chief engineer Gordon Murray sketched out a three-seater coupe, and showed it to McLaren team principal Ron Dennis. An agreement was struck: to make the ultimate road-going supercar.

Taking Formula 1 performance to the road at the height of a bubble of economic prosperity made perfect sense. How hard could it be? Already, the relatively bare-bones F40 was a knockout success, and McLaren’s expertise in the use of composite materials could surely be the equal of Maranello’s tube-frame poster car.

Further, chief engineer Gordon Murray wasn’t interested in benchmarking the usual suspects. Instead, he chose a car he would drive for some seven years: a first-generation Acura NSX. Acura’s original machine sent shockwaves around the world when it was launched, and thanks to input from Senna himself, it was a well-respected driver’s car. However, its daily-driver friendliness was something Murray thought could be applied to hypercar territory.

Further, the F1 almost ended up with a Honda engine. Such would have made a lot of sense, given the two companies’ long Formula 1 partnership, but Honda balked at the request. The specifications required were a maximum power output of 550 hp, with a total weight of 250 kg and a displacement of perhaps 4.5L. Honda decided such an engine was too large for their future plans and declined.

A revvy, peaky, low-torque engine might not have fit Murray’s specifications anyway. He didn’t want turbocharging to be part of the formula; adding boost made great peak power and torque, but it was hard to keep the delivery linear. As the F1 would be a true driver’s car, free from traction control or any other aids, it needed to be as pure as possible.

Happily, BMW was there to fill the void. Specifically, BMW M-division legend Paul Rosche was there. An engineer who joined BMW before they produced the 2002, he’d end up overseeing every great BMW engine of the golden era: the homologation-spec four-cylinder of the E30 M3; the screaming straight-six of the M1 and M5; the BMW-Williams F1 V-10. And the V12 which would become the heart of the McLaren F1.

Under Rosche’s direction, BMW produced a 6.1L V12 with the engine code S70/2. It produced around 620 hp at 7,400 rpm and weighed 266 kg, more powerful and only slightly heavier than Murray’s ideal spec. Another tidbit: the original German–Brit alliance was proposed over after-hours beers in the pits at the Hockenheim F1 race.

The body of the McLaren was built around a carbon-fibre monocoque, the world’s first. Unlike the Ferrari F40, which used a modernized form of 1960s-style GT racing tube-frame construction, the F1 would be just as advanced as McLaren’s Formula 1 machines.

And, like the formula cars, the F1 would get a central seat for the driver, with two flanking seats for passengers. The design was penned by Peter Stevens, who had recently come over from working for Lotus and Jaguar on their supercar programs.

On one hand, McLaren’s brass were very hands-off, and the team was given free rein to create the best car they could. On the other hand, the budget was fairly restrictive, just £8.5M to set up the entire company. Suppliers were asked to provide wheels, brakes, and glass for free – all without being told what the car under development would look like.

The first prototype was driven by Murray on December 23, 1992. From an empty building to a full-fledged company, McLaren had taken less than three years to create something truly astonishing.

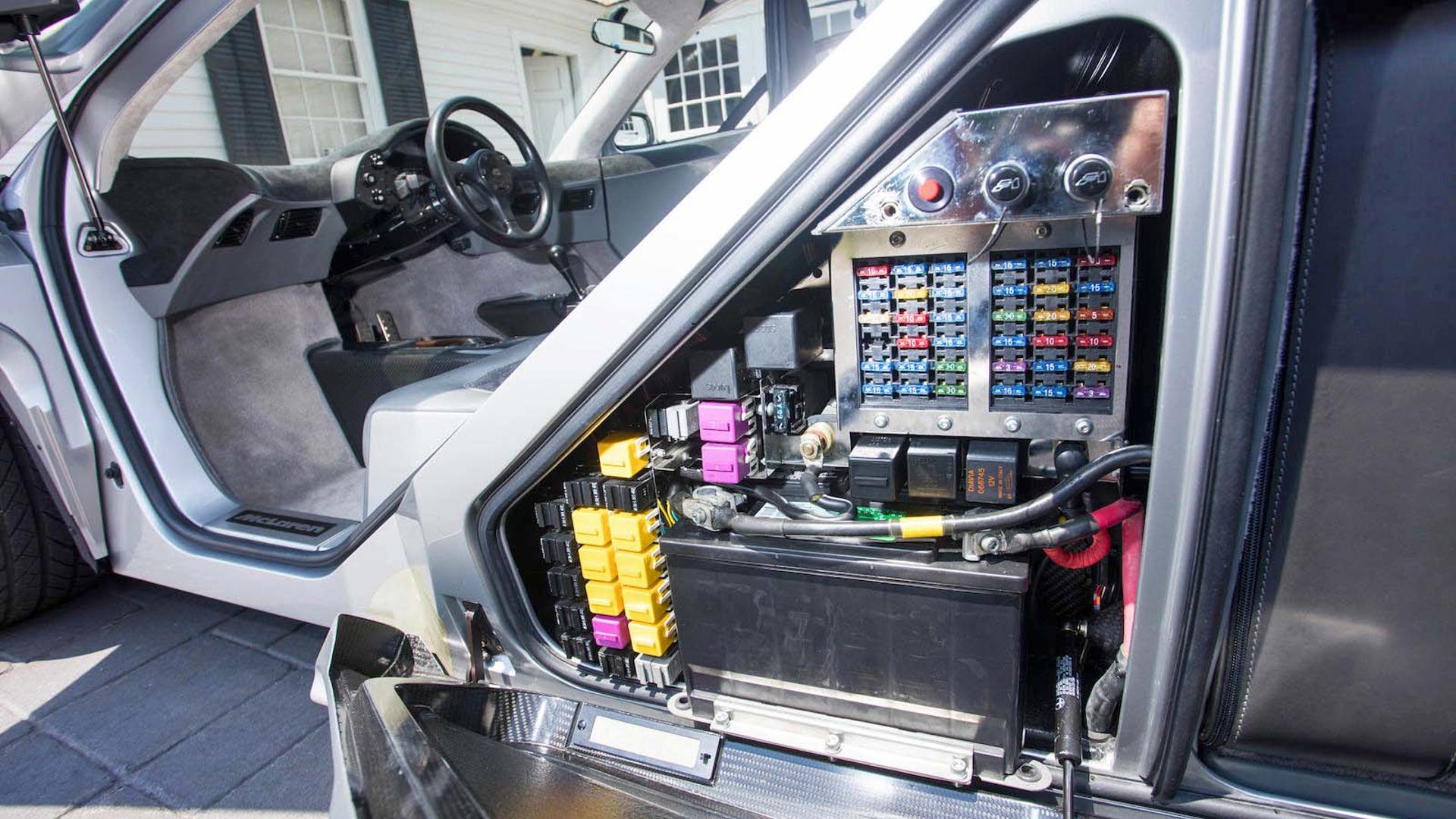

The McLaren F1 was crammed with facts for gearhead geeks to absorb. Its engine bay was coated with 1.6 g of gold sheeting to reflect the engine’s heat. It weighed just 1,100 kg in road-going trim. The leather interior was shaved to half the normal thickness, saving 5 kg overall. The onboard toolkit was fashioned from titanium. In a time before the Internet really existed, it came with a built-in 14.4k modem so you could dial up the factory for diagnostic help. Above 210 km/h, it accelerated faster than contemporary Formula 1 cars, because it had less downforce.

Weighing in at 1,100 kg, the F1 clocked in with a power-to-weight ratio of just 1.6 kg per hp. Acceleration was absolutely blistering if you could get the power down. Zero to 100 km/h came in just over three seconds, but the real insanity happened if you dropped into the power at higher speeds. It would take the F1 less than half a minute of sustained acceleration to hit more than 320 km/h (200 mph), and it would eventually set a top-speed record of 386 km/h.

The numbers are brain-melting, but even more important is the fact that the F1 wasn’t merely a device to smash air like the Bugatti Veyron, but a true sportscar. Think of it as the nuclear option to the Acura NSX’s conventional firepower: it wasn’t meant to be some harsh-edged racer, nor a computer simulation, but a driver’s car of unfathomable capability.

The carbon-fibre chassis gave the F1 outstanding rigidity, but the suspension was fairly softly tuned. Rather than skipping like a stone over imperfections, McLaren’s ultimate road car would absorb them, then blitz onwards on a wave of V12 torque. The sound was ridiculous. The agility was that of a meth-addled mongoose. Yet the livability far surpassed the Italian exotics. The closest in usability, perhaps, was Porsche’s 959.

Like the 959, the F1 would go racing. Such was never McLaren’s intent, and it was almost with reluctance that the factory built the GTR versions. They promptly won the 1995 24 Hours of Le Mans outright, beating the pants off the prototype class. Oh, and by the way: the Le Mans F1 cars were running detuned engines due to power restrictions.

With so few roadworthy examples, you might expect every F1 to be a museum piece, tucked away on a podium. It’s not so. What takes this machine from myth to legend is the way their owners are supported by the factory when they choose to use them.

First, the F1 is so valuable that it has crossed the threshold where mileage no longer matters. It’s built to run, so if they sit around they tend to moulder – better to run up the miles and watch your investment appreciate anyway.

Secondly, the F1 is serviced on time, not mileage. Almost everything is an engine-out service, including the high-cost replacement of the racing-style fuel bladder. You’ve got to do that once every five years regardless of how much you drive the car, so why not participate in one of the 800 km weekend tours run by the McLaren F1 owners’ group?

The future is here. The ultimate McLarens – ultimate Ferraris, ultimate Porsches – are now hybrid machines of immense complexity. It’s hard to understand them.

The McLaren F1, then, is perhaps the last supercar to carry a vestige of humanity about it. It is the product of few hands, working unrestrained by the limits of cost or marketability. It is a machine made to be used, not just displayed. True, the cost of entry is astronomically high. But unlike many expensive cars, the McLaren F1 is not meant to be rolling artwork, displayed only on a concours at Monterey. It is the ultimate driver’s car.