Drivers will voice their opinions about the terrible state of the roads at whoever will listen – social media, elected officials, or that plastic hula dancer on their dashboard.

“Why am I stuck at this light for eternity?”

“Why did they build a four-lane bridge when we need six?”

“Why put a stop sign here, why!?”

“Who designed this!?”

And so on. As a transportation engineer, I’m often on the wrong end of these discussions. But just like a physician, I have the knowledge, background, and skills to analyse infrastructure, consider the context and look at the greater picture.

Critics are everywhere – when in the public realm, receiving credit where credit is due is a rare occurrence, and even more so on social media. Even I have bashed an ill-planned piece of infrastructure. I can, however, appreciate greatness when I see it. Here’s a sampler of roadway successes and failures, as viewed through my own windshield.

The Successes

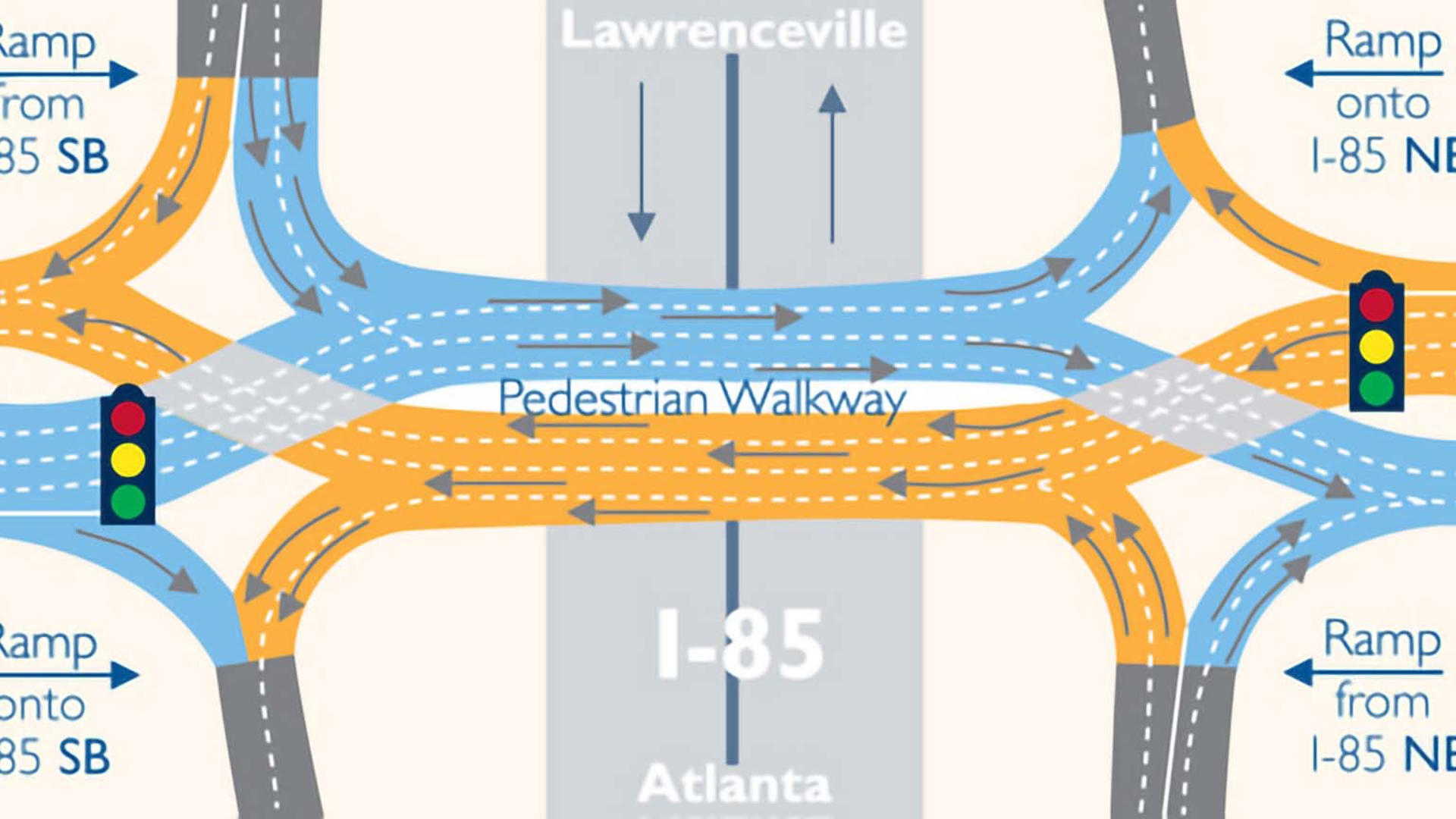

DDI –Diverging Diamond Interchange

A diamond interchange is not a shiny piece of infrastructure. The name comes from math class: when viewed from above, the typical crossing of a highway and an arterial road in tight urban confines forms a roughly diamond-shaped mix of travel lanes and ramps. Diamonds have a built-in design flaw: when faced with a lot of turning traffic, the centre portion – usually an overpass or underpass with no expansion room – becomes congested from all the conflicting turning and through movements. Traffic lights can only do so much.

Enter the DDI – the Diverging Diamond Interchange. Removing left turns from traffic lights is the easiest way to relieve traffic – easy on arterials, no so much at a highway crossing. The DDI replaces the ramp intersections with X-shaped ones before and after the interchange. Traffic diverges to the left side of the road at a simple two-way traffic light, removing all conflicts at the upcoming leftmost ramp. Traffic turning right is ramped off before the X. Simple. Effective. Brilliant. Calgary recently inaugurated Canada’s first application of this design, and I drove through the very first DDI in Missouri a few years back.

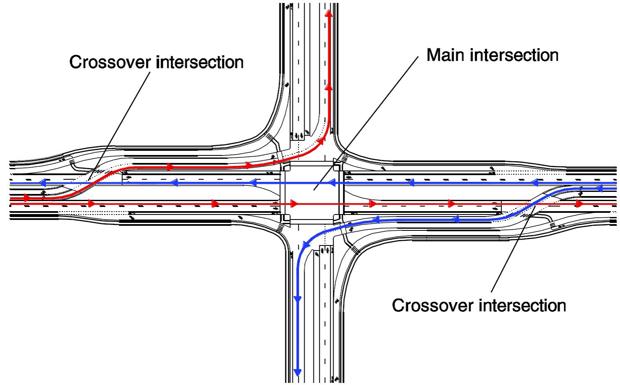

CFI – Continuous Flow Intersection

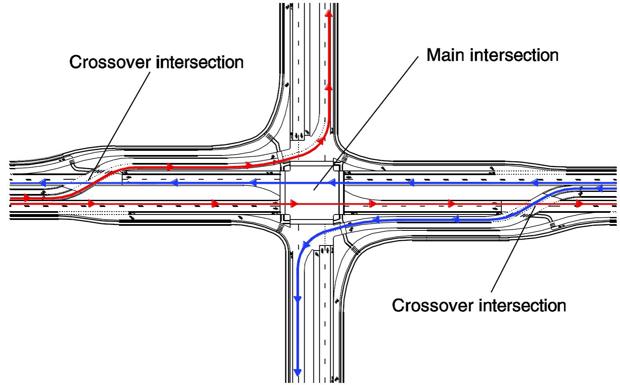

The name says it all. Think of a CFI as a flat, 2D interchange where all turns are “handled” separately from the main direction of travel. A CFI will typically link two heavily travelled, multilane roadways. What the design does is evacuate all the turning traffic before the two main roads intersect. Instead of having a monster of multilane approaches at the signals, the CFI has an efficient two-way signal with no turns – think of the intersection of Dundas and Yonge in downtown Toronto; while not a CFI, the absence of turns makes things more efficient.

To make turns in a CFI, road authorities have to create multiple, smaller intersections upstream and downstream of the main crossing, along with parallel roadways to divert turning movements. These turns are managed without conflicts during the main traffic light “phases” of the centre intersection. It’s a highly efficient design, but for an engineer it’s as daunting to tackle as a 5000-piece puzzle of a swarm of bees. It also requires a ton of room to build.

Confederation Bridge

Building a bridge to Canada’s smallest province was no small potatoes. The Confederation Bridge is a landmark piece of infrastructure, being the world’s longest crossing of open ocean waters subject to ice. Built at a cost of $1.3B between 1993 and 1997, it provides safe and reliable crossings between PEI and New Brunswick all year long.

The shallow waters of the Northumberland Strait allowed a technique that involved the construction of all bridge components on land, which were then moved into place with a heavy-lift catamaran. The 12.9 km bridge, built from high-grade concrete, follows a hollow-beam design that promises a 100-year lifespan. Having taken a one-kilometre walk inside the now 20-year-old bridge, I can attest it is ship-shape.

Millau Viaduct

You don’t have to be a structural engineer to appreciate this beauty, a land bridge that received an “Outstanding Structure Award” from my peers in 2006. This cable-stayed bridge spans 2,460 m over the Tarn River valley near Millau in Southern France. While its deck, at 270 m, is only the 22nd highest in the world, two of its pillars are actually the highest (245 m) and second highest (221 m) in the World. Adding the cable mast, it also has the world’s tallest pillar / mast ensemble at 343 m.

The construction was just as spectacular as the end result. The hollow decks were built on land, and pushed into the void cantilever-style up to 171 m in thin air. Inaugurated in 2004 after three years of construction and 13 years of studies, the Millau Viaduct replaced a busy and deadly stretch of road with its new Autoroute A75 segment.

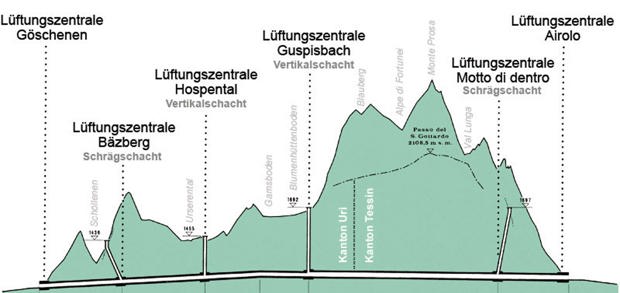

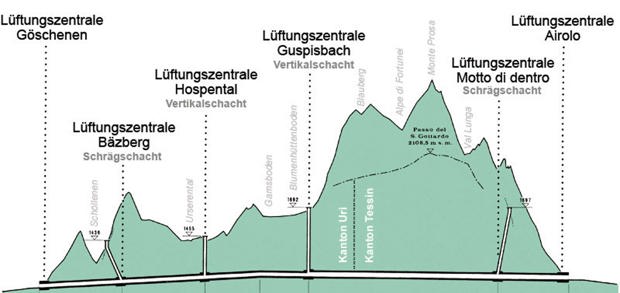

Gotthard tunnel

Switzerland may be a small country, but if you could spread it out flat and smooth like a piece of crumbled paper, it would grow exponentially. The towering Alps have forced the Swiss become tunnel experts, and for this frequent user of the Lafontaine tunnel in Montreal, crossing the Gotthard was an awesome experience. Starting from the German part of the country, one drives down an ever-narrowing valley up to the mouth of the 16.9-km-long tunnel. And everything is written in Italian when you emerge in Ticino. For most users, the Gotthard tunnel replaces the pass of the same name that snakes up and down the Alps at up to 2,106 m of elevation.

Opened to traffic in 1980 after ten years of construction, it was at the time the world’s longest tunnel (it’s now the ninth). The single-bore two-way tunnel will be twinned, with work on the second tunnel scheduled to start in 2020.

The Failures

Place de l’Étoile

Roundabouts are a good thing. Multilane roundabouts are a slightly more complex but still pretty good thing. And then there’s Place de l’Étoile, set around the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. It’s a multilane roundabout on meth. There are so many lanes and trajectories available through this thing that it made absolutely no sense to mark them. So they didn’t.

Officially named “Place Charles de Gaulle”, this traffic circle has twelve branches. Never, ever take a rental car though this, unless you’re a seasoned Paris driver. To best enjoy the zaniness of this thing, use the underground crosswalk and climb up the stairs to the roof of the Arc de Triomphe, look down, and enjoy the show.

The Magic Roundabout

Maybe the British secretly envied Paris’ wretched traffic circle, or the local road authority engineers had interesting herbs in their tea bags – who knows. But the town of Swindon in the UK has a mind-bending traffic circle that is aptly named “The Magic Roundabout”. The six branches meet at a vast multilane roundabout that incorporates five smaller circles. Trying to figure this thing out – remember, the British drive on the left – will have you reaching for the Tylenol.

Not recommended for first-time-in-UK tourists in a stick-shift rental car after a warm pint of Guinness (keep left, look right, keep left, look right, …). Traversing this should be a mandatory test for automated cars (and no, Google won’t have the answer to this one).

Sedona’s roundabout fest

Use with moderation. Maybe engineers from Arizona’s DOT should have considered this little phrase before littering touristy Sedona with twelve – twelve! – successive roundabouts along the 179, the main access route from Phoenix.

Urban planners love roundabouts, the inner circle being a blank canvas for their craft. But here all circles feature identical landscaping, raising the question: “Did we just drive through here?”. Once you finally get to downtown Sedona, your head will be spinning. And it won’t be because of the breathtaking scenery.

Road to Hana

Yes, Maui is a Polynesian paradise, but when one of a destination’s main attractions is a road, expectations are high. And it all sounds very sexy to a car guy: 620 curves hugging a mountainside, over a mere 84 km.

But here’s the reality: it takes on average three hours to make that trek. The road has 59 bridges, usually set in a hairpin, and 46 of them are one-car wide. Plus, the road has a myriad of small pull-outs for sightseeing, none of them clearly marked. Forget your Mille Miglia dreams – this is a rental car parade.

Champlain Bridge

Good ole Canada also has its share of roadway fails. The Champlain is a federal bridge that crosses the mighty Saint Lawrence between Montreal and its South Shore. With 170,000 crossings per day, it’s the nation’s busiest single-deck bridge. Inaugurated in 1962, it’s the second-youngest crossing towards the South Shore. And it’s been failing, fast.

De-icing salt has been eating at the concrete’s structure’s “bones” at an impressive rate. According to media reports, the bridge was not designed to withstand road salt as an economy measure. Two years into its life, nevertheless, the salt spreaders started their evil work, and the bridge has been under life support since 1986 with multiple interventions, with millions spent to this date even as a new bridge is being built alongside it. More millions will be spent dismantling the old bridge, starting in 2020. It’s not a bridge – it’s a bottomless money pit.