At 100 years old, Mitsubishi is one of Japan’s most ancient and revered marques. Or, at least, it should be. In point of fact, perhaps no other Japanese manufacturer bears the brunt of critical skewering more than the triple-diamond: ever since Suzuki quit the field, Mitsubishi hasn’t really been able to claim superiority over any one of the other Japanese mainstream brands.

Cars like the economy-minded Mirage and the positively ancient Lancer don’t bear comparison when lined up against the competition. When the Outlander crossover manages to summon up a half-decent effort, it’s almost a surprise. This from the company that once produced the rally-champion EVO, the Dakar-crushing Pajero, and the techno-wizardry of the twin-turbo 3000GT. What happened?

Somewhere, on the thirtieth floor of some monolithic zaibatsu corporate office, an employee of one of Mitsubishi’s massive non-automotive divisions – shipbuilding, construction, component supply, industrial, electrical – gets off on the wrong floor and takes a look around in surprise. “We still make cars?” the salaryman asks in surprise. They do. And, even if there’s not much in the current portfolio to really stir the imagination, maybe it’s time to give Mitsubishi some of the respect they deserve.

Mitsubishi’s story begins with the establishment of a shipping empire. Choosing a triple-diamond crest to pay honour to the clan that had given him his first foothold in the business, founder Yataro Iwasaki began some of Japan’s first trading routes with Korea and overseas. Growth soon followed as the formerly closed-off island nation began opening up to trade.

With that growth came modernization and a growing wealth. Projecting a demand for the motorized revolution he’d seen while studying overseas, Yataro’s nephew Koyata came up with the Mitsubishi Model A, a copy of the Fiat Tipo 3. A luxury product for Japan’s new executive business class, the 35hp Model A was Japan’s first mass-produced car, even though production levels were fairly low. Only 22 were built and sold over a four-year period, each one featuring hand-made touches like a white-cypress-lacquered rear cabin.

As the 1920s began, Mitsubishi turned their efforts towards commercial equipment, and eventually towards arming the Japanese war machine. Perhaps the best-known of the Japanese aircraft that fought in WWII was the A6M Zero, a wickedly quick dogfighter. Fast though it might have been, the skies over Japan soon belonged to American heavy bombers, and both Mitsubishi and its factories were smashed to pieces. The once-mighty company was reorganized into dozens of smaller units.

Between the end of the war and the 1960s, Mitsubishi was a player in the rebuilding of Japan, making the three-wheeled cargo vehicles that would be ubiquitous throughout a fuel-starved land. They also formed some unusual partnerships, building Willys Jeeps under licence, and distributing Mazda-made three-wheeled motorcycles.

With the 1960s came the first hints of the Japanese automotive renaissance, as Mitsubishi began producing the Colt and the Galant. It would take until 1970 for Mitsubishi Automotive to properly break out on its own, and by 1971 the company was successful enough to look for overseas partners.

In 1971, Mitsubishi and Chrysler signed a deal allowing the Colt to be brought over and rebadged as a Dodge. Both companies were playing to their strengths, as the American manufacturers struggled to meet market demand for smaller, more efficient cars. Chrysler had the distribution, Mitsubishi had the fuel-sippers.

Yet if the North American market saw the new Japanese captive imports as basically cheap, efficient, disposable transport, Mitsubishi was making something of a name for itself as a performance brand. In 1973, the Lancer 1600GSR began winning rallies in Australia, and then went on to win the 1973 Safari Rally in Kenya. Here it beat well-supported Datsun efforts, and began Mitsubishi’s long association with rally.

The 1980s saw Mitsubishi arrive in North America under its own flag at last, and stir up interest with the Starion coupe. A competitor to the likes of the Mazda RX7 and Toyota Supra, the Starion remains a semi-forgotten collectible featuring pure-’80s box flares and turbocharged power.

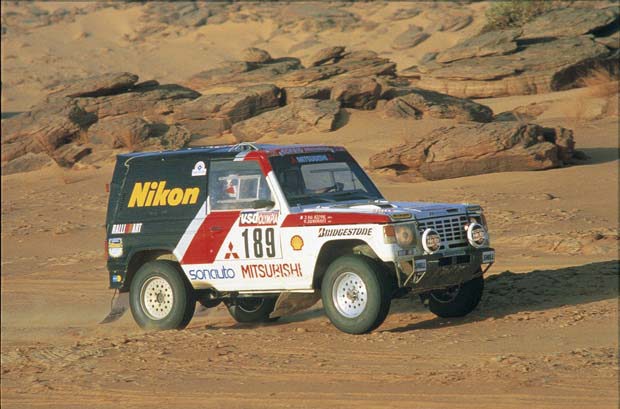

At the same time, the Mitsubishi Pajero – which North Americans would receive as the Montero – won the 1985 Paris-Dakar rally, a gruelling cross-desert race. Again, this was Mitsubishi planting a flag it would raise time and again, winning twelve more Paris–Dakar endurance challenges over the succeeding decades. The triple-diamond remains the most successful manufacturer in Dakar racing.

In the 1990s, some hints of this all-weather, all-terrain performance aptitude began to leak through to rally fans, as Mitsubishi’s success with the Lancer Evo began to grow. However, the Evo was forbidden fruit in Canada, and the closest we got were the Diamond-Star Motor cars, universally known as the DSMs.

Another partnership with Chrysler, the DSMs were built in the quaintly named town of Normal, Illinois. The base-model, front-wheel-drive machines fit the name of the town, but stuff like the Eagle Talon TSi was a little stouter. The Talon, the Plymouth Laser, and the Mitsubishi Eclipse all came with 2.0L turbocharged power and all-wheel-drive at their highest trim levels, and while there were some Achilles’ heels to work out, all were capable of being tuned to huge power.

As a result, a DSM ended up becoming the star of the first of The Fast and The Furious movie franchise, in the form of a bright green 1995 Mitsubishi Eclipse. Granted, there was a bunch of movie-magic nonsense to endure (spinning out at 225 km/h in a parking lot, anyone?), but the Eclipse’s 4G63T four-cylinder was the real deal.

At the same time, the Mitsubishi 3000GT VR-4 came to Canada as the Dodge Stealth R/T. Never quite getting the same hero worship as the twin-turbo RX7 or twin-turbo Supra, the Stealth R/T was nonetheless an absolute powerhouse. A combination of turbocharged V6 horsepower and all-wheel-drive gave it quicker acceleration than many of its rivals, and it had plenty of overhead for tuning. Further, while it was notorious for being heavy, even just stripping out the seats for lightweight racing versions put the 3000GT/Stealth into the same weight class as the rest of the Pacific muscle heroes.

But for most Mitsubishi fans, there’s only one true hero car: the Lancer Evo. We had to wait, as Canadians didn’t get our shot at the Evo until 2008, but it was worth it.

The tenth-generation Lancer Evo, sometimes called the Evo X, came equipped for battle with many of the same elements as the Subaru WRX/STI. However, it had a much more clever torque-vectoring all-wheel-drive system, better steering, and an available dual-clutch gearbox.

Where the STI felt set up for a gravel stage, with soft suspension and loose handling, the Evo was a tarmac scalpel. Autocrossers loved them, and so did track rats. Best of all, as they were based on a standard four-door compact sedan, the Evo wasn’t all that impractical.

However, something changed at Mitsubishi, and not for the better. The Lancer that’s sold today doesn’t have an Evo variant, and is a decade-old platform. The Outlander crossover is competent enough, but can’t match its competition for sales or technology.

It’s almost as if the automotive division of Mitsubishi is in hibernation, hoarding development dollars while waiting to see how the all-electric future pans out. They’re always good for a couple of wild-looking concepts at auto shows, but their current offerings don’t seem all that futuristic.

But perhaps Mitsubishi is taking the long view. If the combustion engine is a dead end over the short term, why pour dollars down the drain? With the launch of their e-Evolution crossover concept, perhaps Mitsubishi isn’t giving up on performance, they’re just looking to the future of it.

Divorce yourself from nostalgia, and things are actually pretty good. There’s a floor-mounted battery back that’s mounted inboard to centralize weight. There’s a trick all-wheel-drive system that borrows from a rallying past. There’s a triple-motor electric drive system that can shunt power where you need it, right now.

If we’re lucky, maybe what we’re seeing right now isn’t Mitsubishi winding itself down. Instead, maybe this is just a resting period before the next stage of Evolution.