Christmas Eve. Chances are, you’ve already done a fair bit of travelling this weekend and have a bit more in store – visiting friends and family, stocking up on groceries, maybe doing some very, very last-minute gift shopping. It’s the most wonderful time of the year, they say. And nothing says holiday spirit quite like the magic that is complete and total gridlock.

These days, you can option a car with lane-keeping and radar-assisted cruise, which can take a load off your mind when inching down the highway. In fact, there are even cars which can take over every aspect of driving from on-ramp to off-ramp (where laws permit, such as in Germany). It’s wonderful stuff – if you’ve got one of these vehicles.

What if you could stop the traffic jam before it began?

What these technologies don’t address is the source of all that traffic – the long lines of vehicles backed up into the intersection, the road closures from construction or accidents, the logjam where arterial roads converge.

And that’s where the Urban-X initiative comes in. A collaboration between Mini and venture fund Urban Us, Urban-X is a start-up incubator, which is a fancy way of saying “we throw money and expertise at people with clever ideas that have an actual chance of seeing daylight.”

These ideas all revolve around improving the urban landscape and the experience of people who work and live there; but they can range from projects that directly impact automotive technology (such as Lunewave’s high-performance radar sensor system), to projects that address urban infrastructure (Roadbotics’ automated pavement-assessment technology), to the decidedly quirky (Sencity’s TetraBIN, an interactive trash can that’s connected to Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram). In terms of real-world implementation, they can be as immediately physical as Upshift’s car delivery service, or as abstract as Qucit’s AI-optimized city management software (which in no way resembles the basis of a summer sci-fi blockbuster).

Individually, the projects have clearly defined goals and boundaries; taken together, you can imagine a scenario where your car, detecting slowing traffic or an accident up ahead, sends a message to the city’s traffic control centre. From there, the information is forwarded to navigation services like Google Maps or Waze. City staff, meanwhile, model the impact on traffic based on real-time data, and adapt traffic light patterns to accommodate the delay. Traffic cans surrounding the area warn pedestrians of a slowdown ahead, prompting some to take the subway instead of surface-level transit.

It’s not science fiction – traffic control centres already do most of the above! The difference these technologies make is in the timeliness of data and the quality of analysis. Current methods only reveal traffic jams after they’ve already had a quantifiable, significant impact; and redirecting cars to alternate routes could exacerbate pavement damage, creating potholes (and possibly accidents) where there were none before. AI assistance allows the city to easily consider multiple streams of data and make effective recommendations to motorists, pedestrians, and transit authorities.

What if you got rid of the commute altogether?

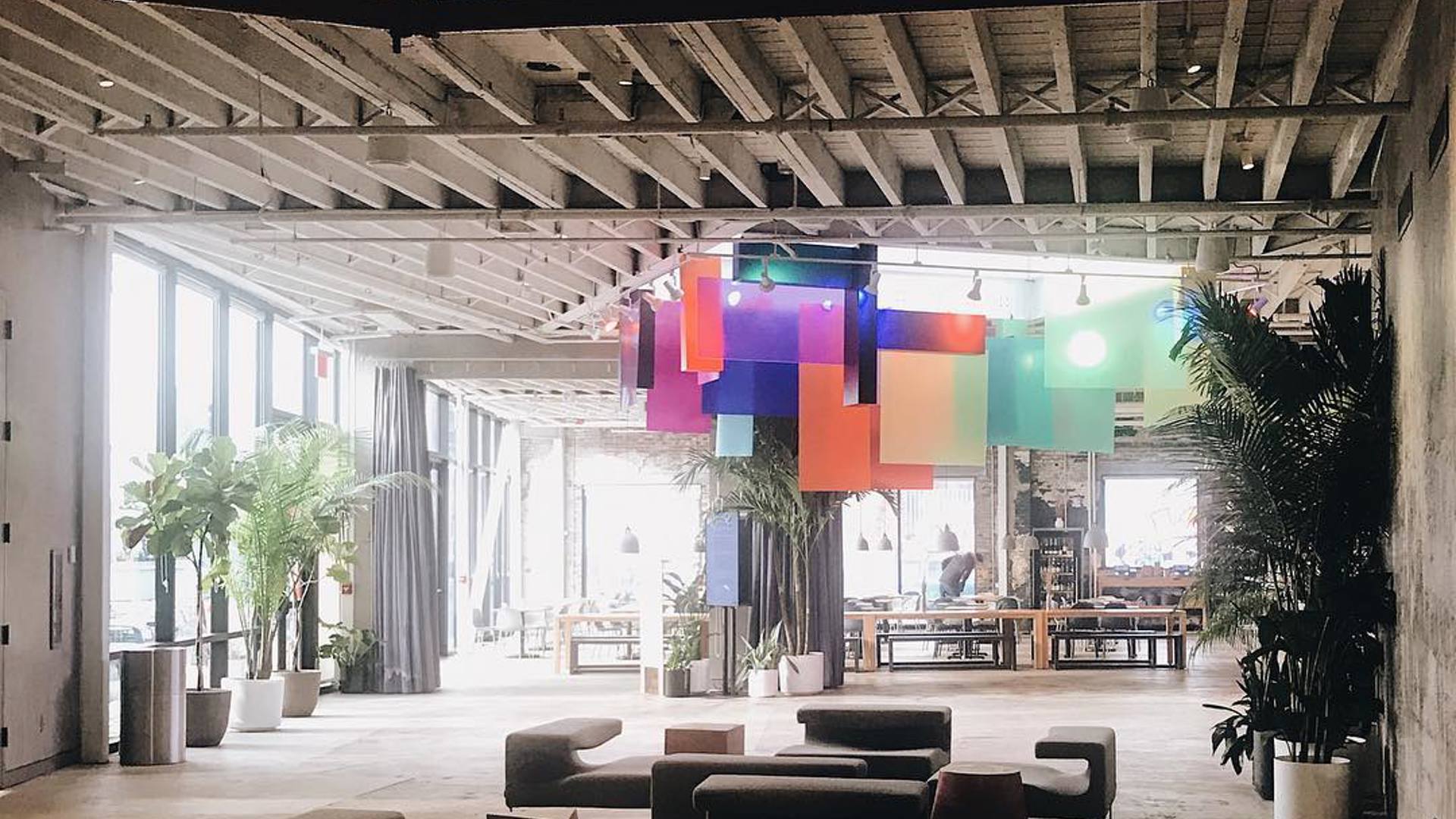

Urban-X is based in A/D/O, a “creative space” founded by Mini in Brooklyn, New York, and named after the Amalgamated Drawing Office of the British Motor Corporation, the team that designed the very first Mini. Broken down into its components, the A/D/O comprises a shared working space, a restaurant, a gift shop, indoor and outdoor exhibition/event spaces, and of course the Urban-X offices. It’s an unconventional vision of what “work” can look like.

Walk through the doors and it looks like a cross between the ground floor of an office building and an overgrown coffee shop. Visitors are immediately greeted by an art installation, which changes from month to month – on my visit it was “Tetromino” by Edward Granger, an arrangement of acrylic glass rectangles that illustrate the transformation of colour from digital representation to physical manifestation, with the added effect of drawing the eye up toward the building’s “periscope”, a domed skylight with mirrors that allows the observer to simultaneously see the A/D/O’s immediate environs in Brooklyn juxtaposed with the Manhattan skyline across the river.

During the day, the restaurant to the left of the entrance, separated from the industrial-chic foyer only by a thick curtain, has its tables arranged in long, cafeteria-like columns, and its seats are mostly occupied by twenty-somethings on their MacBooks. Additional benches and tables populate the main space; these too are taken up by creative types hunkered over backlit Apple logos. For the number of people present, it’s surprisingly quiet, with only the subtle ebb and flow of scattered conversations washing off the concrete walls.

A row of meeting spaces lines the rear wall, for presentations to clients both local and remote (via teleconferencing equipment in each room). Through the glass doors in the back you’ll find the outdoor exhibition space, in this instance holding an Urban Cabin concept home by Mini Living. The gift shop to the right of the entrance rounds out the publicly accessible portion of A/D/O. A wide corridor leads to the private area: members-only desks and crafting equipment on the right, and the Urban-X offices on the left.

The A/D/O wouldn’t look out of place on a university campus, and indeed, there’s something quietly academic about the open-concept floor plan, accented with creative works designed to inspire without becoming distracting. It can easily become a second home for freelancers and entrepreneurs. But is it a proper workplace? (If you get inspired and manage to convince your boss to let you work remotely, I take full credit.)

From “what if?” to reality

Let’s go back to Urban-X. The nine hand-picked start-ups have five months (up from just three months for the first cohort) from the day they arrive at the A/D/O, to Demo Day, when they present their ideas and prototypes to the public. Though the term “incubator” evokes an image of a warm, nurturing environment – and certainly, the Urban-X participants are mentored by a group of passionate, knowledgeable experts – it’s really more of a pressure cooker, a flat-out run from start to finish: developing their concept into a working prototype, honing their business savvy, and meeting with potential customers, investors, and partners.

Barriers to success can come from anywhere: Swiftera’s better-than-satellite, high-resolution images rely on a camera unit most easily described as a drone attached to a weather balloon, and in addition to building the camera hardware and coding the control software, the team also has to clear regulatory hurdles to literally get off the ground and operate in high-altitude airspace; back on terra firma, you only need to look to Kickstarter for high-profile examples of successfully funded projects that ultimately fell apart not from external pressures, but due to inexperience and mismanagement.

Though Urban-X invests up to US$100,000 in each start-up, the real benefit of the program is the wealth of expertise and the vast network of resources the companies can tap into. It is an incubator in the sense that it’s the first step for these companies, which will go on to secure further rounds of funding and refine their prototypes for deployment – possibly partnered with others they’ve met through the program.

Initiatives like Urban-X and the A/D/O are Mini’s answer to the question “What if there were no drivers?” Where does an “urban go-kart” fit into a future where autonomous cars reign supreme in city streets and on the highway? It might seem a bit of a stretch for a car manufacturer to invest in smart, urban hydroponic farms (Farmshelf), or workplace optimization based on occupancy and air quality (Envairo); but as automobiles evolve, so must the companies that make them. The “driver” can no longer remain some abstract mass weighing between 100 and 300 pounds sitting within the confines of a car’s sheet metal on an engineer’s sketchpad, because these same engineers are actively developing their computer replacement.

So how do you get someone to put their hands on the wheel and drive, if their car can drive itself? The answer is to improve the driving experience, from the asphalt up, so that when a driver opts to take the reins, the experience is satisfying, rewarding and, most importantly, fun.