If you grew up in Ontario, then you’ve undoubtedly heard that Yonge Street is the longest street in the world. And if you’ve got a curious streak, you might also have wondered what it would be like to travel its entire length.

I’ve often pondered this myself. But this time, I have to confess that the final proposal was my daughter’s idea.

Before we moved out of downtown, my daughter went to school on Toronto Island. This requires travel on the city ferry, which can be prone to delays in bad weather or busy seasons. Once in a while, that meant we’d be left wandering near the docks with time to kill.

One such occasion saw us head west on Queens Quay toward Yonge Street. There, tucked into a harbour lookout on the south side, text is cast from metal into the sidewalk: “This is the start of Yonge Street – The Longest Street in the World.”

“We should drive the whole thing one day,” my daughter said as she examined the text. She would have been 5 years old at most; we hadn’t been on many road trips yet. But already, the idea of jumping into a car and following a road just to see where it goes was inspiring her.

I kept the idea in my back pocket, and this summer, the stars aligned. We loaded up a 2019 Chevrolet Colorado ZR2 and a 2017 Airstream Flying Cloud – the latter being supplied for evaluation by the closest Airstream dealer to the Greater Toronto Area, Can-Am RV in London, Ontario – and set off to cover every single one of the 1,896 kilometres that make up the legendary Longest Street in the World, from the Toronto harbourfront all the way to the United States border at Rainy River.

It took us six days to cover this distance, albeit with some side trips along the way. Despite planning not to spend more than six hours on the road on any given day, this made for a hectic pace. Eight to 10 days would be a better timeframe for enjoying the many sights, parks, and wilderness adventures to be discovered along the way.

DAY 1 – Toronto to Orillia

To tell the tale of Yonge Street requires starting at the beginning – which means that, yes, I drove a truck and 19-foot trailer into the heart of downtown Toronto just so that I could turn onto Yonge Street from Queens Quay.

Not so long ago, the start of this drive would have been punctuated by a Toronto icon. Captain John’s, a seafood restaurant housed within a docked boat, sat at the foot of Yonge Street beginning in 1975. The first ship, the MS Normac, sank in 1981 after a city ferry collided with it; the MS Jadran replaced it and stayed in the same spot until it was towed away and scrapped in 2015.

Although the restaurant and the Jadran are gone, a city street sign marking Captain John’s Pier stands today as a reminder that once upon a time – back when Captain John’s was a prestigious dining destination, Speakers Corner was a television icon, the Rolling Stones rocked the El Mocambo, and Honest Ed’s lights and signboards kept Bloor and Bathurst ablaze – Toronto had more character than people gave it credit for.

As for that sidewalk inscription, it’s looking a bit decrepit these days. The concrete is cracked around it and traps discarded trash, an unceremonious state for a street with noble origins.

The first Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, John Graves Simcoe, ordered a road to be built over a First Nations trail that marked the shortest overland distance between Lake Ontario and Lake Simcoe. His vision was purely strategic: according to the historic plaque that sits just north of Queens Quay on Yonge, Simcoe saw the route as having military and commercial potential.

The former purpose ended relatively quickly, but the latter is unquestionable. Driving north through downtown, past Yonge-Dundas Square, then through Yorkville, Midtown, and under Highway 401 in North York, Yonge Street is a long-established centrepiece for multiple Toronto neighbourhoods.

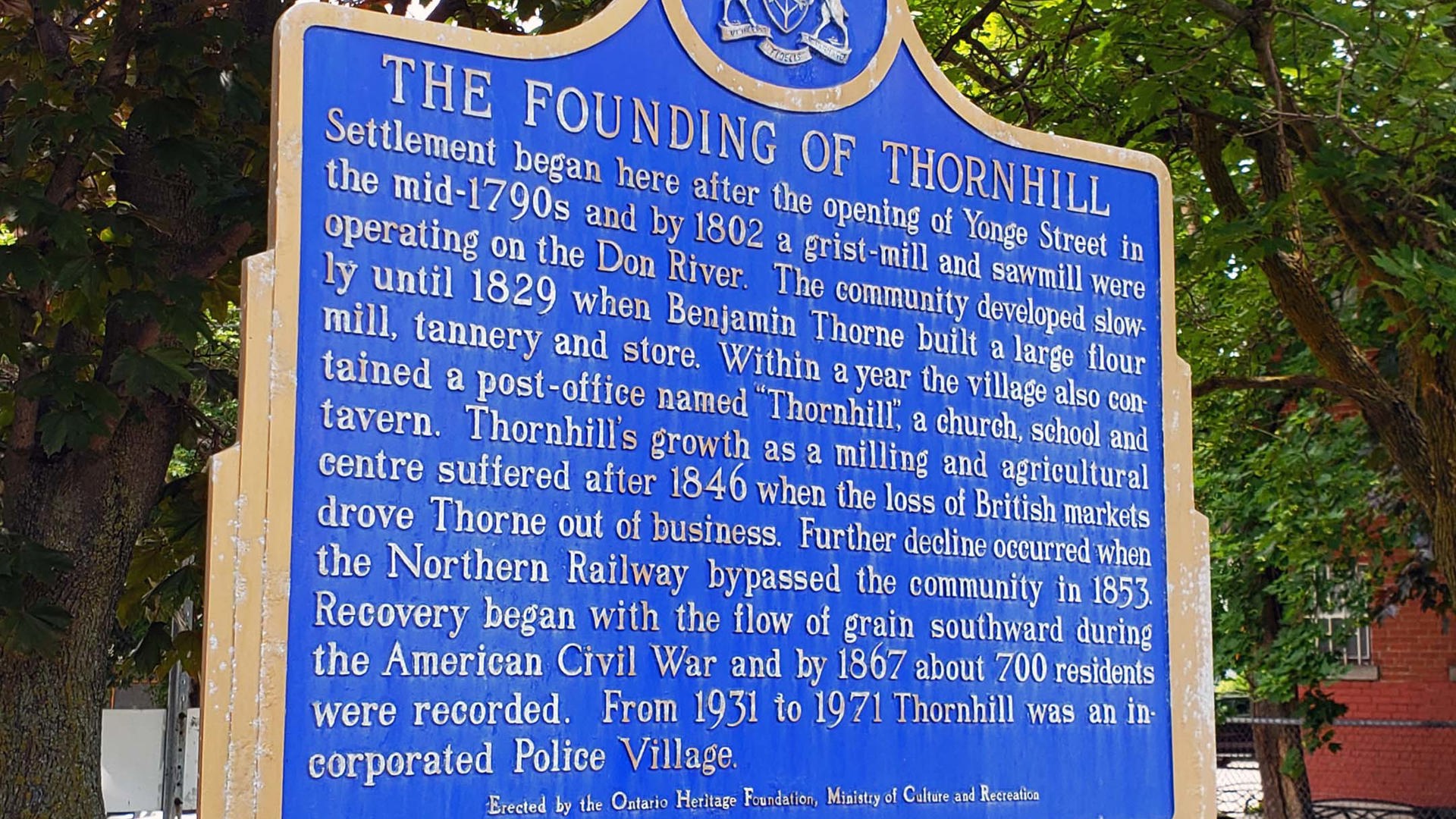

And its role as a de facto Main Street doesn’t end at the City of Toronto’s current border of Steeles Avenue. As settlers followed it north, new territory opened, and today it’s dotted with historical plaques honouring the villages that were founded along the way: Thornhill, Richmond Hill (which has since enveloped Oak Ridges), Aurora, and Newmarket.

North of Green Lane, the road takes a jog to the west. This is where that whole Yonge Street versus Highway 11 thing starts to get confusing.

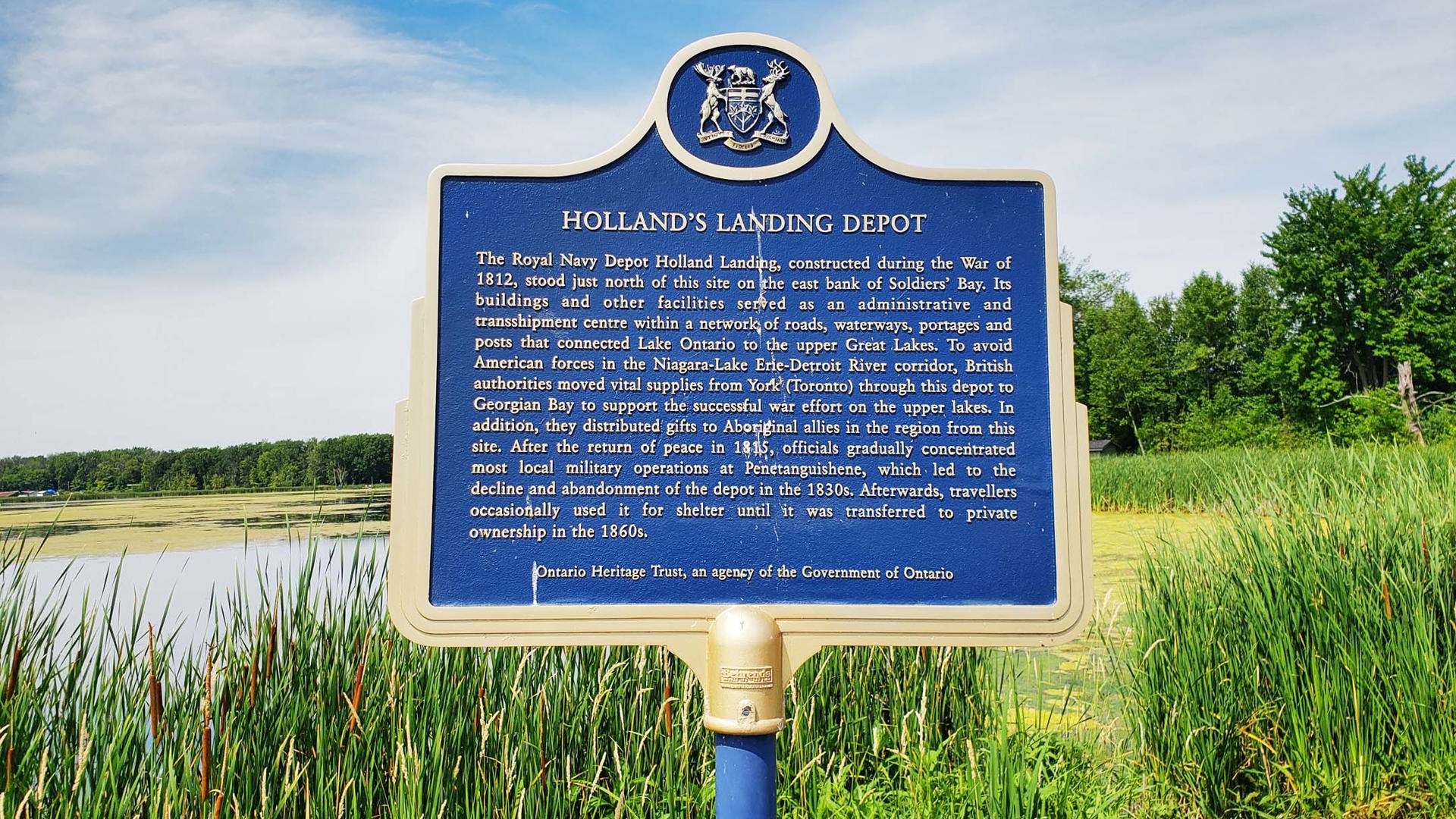

The road that’s still named Yonge Street continues into Holland Landing, part of the town of East Gwillimbury. There’s a small park there, aptly named Anchor Park, where a small piece of Yonge Street history sits largely unnoticed: a British-forged anchor, which was hauled up the road from Lake Ontario on an oxen-pulled sleigh led by local farmers. They were to deliver it to the Soldiers’ Landing military depot just north of here, but they received word that the War of 1812 had ended, so they dumped the anchor where they stood and headed home. The anchor was moved into this park in 1872 and has been here ever since.

Yonge Street continues north to Queensville Sideroad, where a small spur of it gives access to a golf club and then stops abruptly at the Holland Marsh.

But once you head back to the point where the road swings to the west, that stretch is signed as Highway 11 – even though, according to the province, Highway 11 doesn’t officially start until north of Barrie. It’s all very puzzling.

To trace the historic route of Highway 11 from before this section was downloaded to its municipalities, follow this road until you reach Barrie Street in Bradford – this turn is tight, and trucks are not permitted; I just barely made it with my Colorado and Airstream combination, so larger vehicles should take the marked detour – then stay with it as it becomes Yonge Street again and enters Barrie from the south. Turn right at Essa Road, then continue as it becomes Bradford Street. Turn right onto Dunlop Street to follow it around Lake Simcoe’s Kempenfelt Bay and turns into Blake Street and then Penetanguishene Road. Shortly thereafter, you’ll reach the hamlet of Crown Hill and the modern-day starting point of Ontario Highway 11.

Or, you know, just take Highway 400. With no traffic, using 400-series highways to get here takes just over an hour; following this route took us nearly four hours. Sometimes, development has its positives.

Overnight at Bass Lake Provincial Park

This small park feels surprisingly remote given how close it is to civilization, being just 10 minutes from Orillia off Highway 11. The campsites are nicely private, and while walking is hilly in places, there’s a long walking trail that traces the waterfront and leads to a quality swimming beach. It’s a popular spot for day trips from the city.

DAY 2 – Orillia to Temagami

What makes the stretch of Highway 11 between Orillia and Gravenhurst such a treasure is how little it has changed since the early 1980s, when it was converted to the right-in-right-out (RIRO) system that prevents left-turning vehicles from impeding traffic flow. While Highway 69 to the west continues to be widened and divided, Highway 11 is still home to the unbroken median walls and turnaround overpasses that define the RIRO style, as well as the homes and businesses that this system has allowed to remain in place.

One of the beneficiaries is Webers, a hamburger joint located 10 km north of Orillia. Once upon a time, stopping here for a burger and a milkshake was such an indestructible cottage country tradition that people would park on the southbound shoulder and run across active highway lanes to join the long lineups, even after the median wall was built. This led to the restaurant’s owners purchasing a pedestrian bridge that was once part of the Skywalk to the CN Tower in downtown Toronto.

The RIRO section ends in Gravenhurst as the highway turns sharply to the east to divert around the southern tip of Lake Muskoka. My daughter and I would have stopped here to complete the Parks Canada Xplorers activities at Bethune Memorial House and add to our tag collection, but we covered this one on our Georgian Bay Circle Tour road trip a couple of years ago.

The route continues as a divided four-lane highway to the west of Algonquin Provincial Park until it reaches North Bay, which welcomes travellers as the self-proclaimed Gateway of the North. A very nice beach and play structure offer a welcome opportunity to dip your toes into Lake Nippissing and give little legs a stretch. And as it leaves North Bay, Highway 11 shrinks to two lanes and remains that way for much of its length.

Roughly 60 km after that transition is Marten River Provincial Park, where we stopped in to visit the park’s historic logging camp. Faithfully recreated from the reports of men who worked at a nearby camp into the 1950s, it gives a fascinating glimpse into a rugged and taxing trade that was often practiced by farmers seeking winter income. It also gave me an opportunity to share The Log Driver’s Waltz, an iconic Canadian short film if ever there was one, with my daughter in a context that brings its significance into focus.

Overnight at Finlayson Point Provincial Park

It would just be wrong to pass through paddling country without stopping to partake, so we were delighted to find that the reception desk at this beautiful park offers self-serve canoe and kayak rentals, complete with life jackets and emergency kit, that unload directly into Lake Temagami.

DAY 3 – Temagami to Matheson (with some detours)

We didn’t make a lot of progress on Highway 11 on this day, but that’s because we had several side quests to complete.

First, we took Highway 11B into Cobalt, a former silver mining town and National Historic Site. This was a late addition to our itinerary, so we were only able to have a quick look at the old mine headframe and take a quick drive through town. But those with more time to invest can visit the museums, take the tours, and walk the trails that detail the town’s contributions to another challenging trade upon which Canada was built.

After doubling back so as not to miss even a metre of Highway 11, we turned off again at Temiskaming Shores and drove east to enter Quebec and visit Obadjiwan-Fort Témiskamingue National Historic Site. This is a long detour but a scenic one with views over Lake Temiskaming and far more agricultural land than we’d seen since we left the Holland Marsh, most of which was verdant and aglow with the bright yellow flowers of the area’s canola crops.

Not much remains on these grounds in the way of historic structure, but the displays that replace them paint a vibrant picture of what life was like at this trading post, where First Nations people exchanged pelts first with the North West Company and later with the Hudson’s Bay Company. My daughter learned how natural materials were used to make canoes and how business operated during the annual spring trading season. The gift shop unintentionally pays homage to the roots of this place by being its own thoughtfully stocked trading post of sorts. Though it’s well out of the way for most travellers, we thoroughly enjoyed the experience of earning another Parks Canada Xplorers tag and could easily have spent at least half a day there – maybe longer had we thrown in a picnic and a swim at the pebbled beach along the access road just outside the site.

We returned to Highway 11 by looping back around the top of Lake Temiskaming and northbound to our final stop of the day, Thornloe Cheese, which is on the highway just southeast of the village of Thornloe. I became aware of this place because their Devil’s Rock, a nippy blue cheese coated with a signature black wax, was one of my dad’s favourites. The storefront has ice cream, plenty of dried meats like jerky and pepperoni, an expansive candy selection, and many shelves of cheese, including curds in a wide variety of flavours (but available fresh only on Mondays).

Overnight at Kettle Lakes Provincial Park

This isn’t on Highway 11 – in fact, it’s about halfway between there and Timmins, so it’s a little out of the way – but it’s the closest park to the highway with camping facilities in this part of the province. The loop road, albeit pretty rough in spots, offers access to several of the park’s 22 lakes, formed by glaciers and leaving behind many isolated fishing and swimming spots.

DAY 4 – Matheson to Hearst

The town of Cochrane plays several important roles for Ontario. It’s the starting point of the Polar Bear Express rail service to Moosonee and James Bay. It’s also the point at which I began to notice many more Franco-Ontarian flags: the green and white backdrop topped with a fleur-de-lys and a trillium is the symbol of Ontario’s French-speaking communities, which are heavily concentrated in the north. Cochrane is also the point at which Highway 11 takes one big left turn and goes from being a north-to-south to an east-to-west route.

Just before entering town from the south, there’s a plaque marking the 49th parallel, the latitude that forms the southern border between the western provinces and the United States. The vast majority of Canada is north of this line, and yet it took us three days and more than 700 km to get here.

Our big stop of the day was the Cochrane Polar Bear Habitat, the largest human care centre in the world dedicated solely to polar bears. This facility takes in bears that for whatever reason are unable to survive in their natural environment. There’s an active research facility on the grounds, and there’s even a small wading area where children can play in water shared with some of the more friendly bears – separated by very sturdy plexiglass, of course – along with a small replica heritage village with a restaurant. For those who grew up around snowmobiles, a small but truly excellent snowmobile museum is next door to the reception building.

Once we departed Cochrane, we carried on more or less straight through to Hearst, a drive of more than 200 km. That’s where my daughter encountered a roadside sign whose words are burned permanently into her memory: “Last McDonalds for 500 km.” The horror!

Up to this point in the journey, while the towns and villages have become more thinly spread and sparsely populated, we’d never been more than a few minutes away from some semblance of civilization. But that was about to change.

Overnight at Fushimi Lake Provincial Park

Located just west of Hearst, this is one of the northernmost Ontario provincial parks reachable by road, and yet it has a full complement of facilities and is well-populated by friendly locals who stay for the season to enjoy the beautiful lake and its excellent fishing. I even had 4G cell service once we were lakeside. The mosquitoes are large enough to carry you home and there’s a permanent boil water advisory, so bring lots of drinking water and bug spray/netting. Otherwise, we thoroughly enjoyed our overnight stop.

DAY 5 – Hearst to Kakabeka Falls

I’m very glad that I heeded the advice I’d read to fill up in Hearst before continuing to the west. Despite having more than a half tank when I stopped, I was down to under a quarter tank in the Chevy Colorado by the time I reached the next gas station 250 km later, just outside Geraldton.

This isn’t the most scenic stretch. Highway 11 was built for industry, not for tourists, so this section goes past a whole lot of logging and mining roads, First Nations communities, and trees and rocks and rocks and trees. It’s a bit of a slog, and cell service is spotty. But it was very rare that I wasn’t within sight of a transport truck or some other highway user, so I never worried that we’d be waiting hours for help if something went wrong, which has its comforts.

This is the stretch where I was most grateful to have the Airstream along. While towing surely plays its part in the need to plan out fuel stops, having a restroom on hand at all times is priceless in remote areas when there’s a young one along.

We made an unscheduled stop at McLeod Provincial Park for lunch simply because the timing worked out. The waterfront day use area turned out to be a nice place for a picnic.

From Jellicoe the scenery starts to improve, and then roughly 50 km north of Nipigon there are suddenly towering cliffs formed from columns of rock, offset by abundant waters and rolling hills. The Palisades of the Pijitawabik are formed by a geological phenomenon called columnar jointing, which ends up creating one of the most picturesque segments on the entire highway.

We didn’t linger long in Nipigon or Thunder Bay because we knew we’d be coming back this way. Instead, we carried straight on to our ultimate reward after a long day of driving…

Overnight at Kakabeka Falls Provincial Park

The best thing about the second-tallest waterfall in the province, located 30 km west of Thunder Bay, is that the area surrounding it is protected by Ontario Parks, so it’s surrounded by natural beauty instead of theme parks. We visited the swimming hole, but the water is silty and subject to the output levels of the hydroelectric dam upstream; focus your time on the trails surrounding the falls instead, which captivated us for hours.

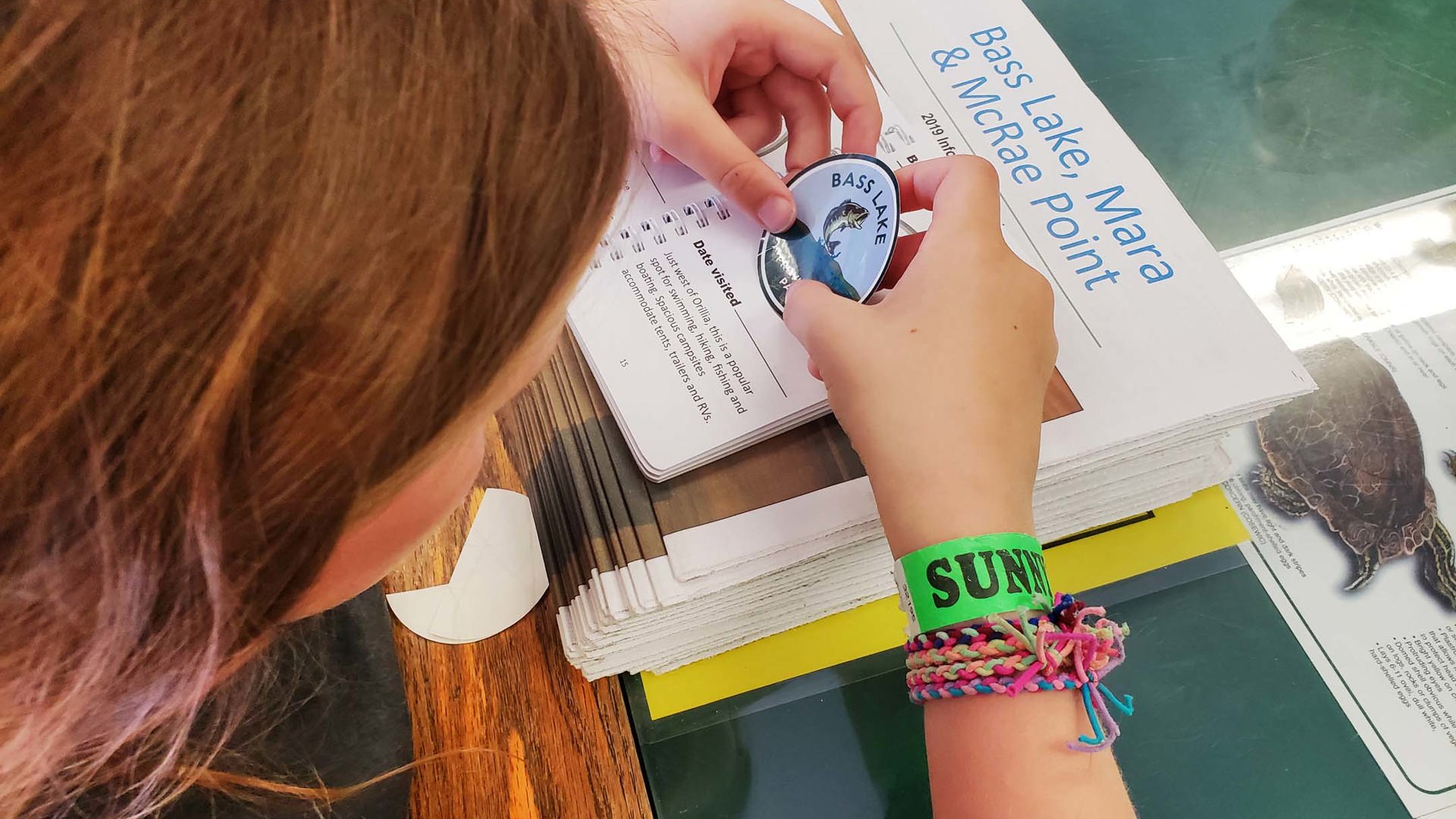

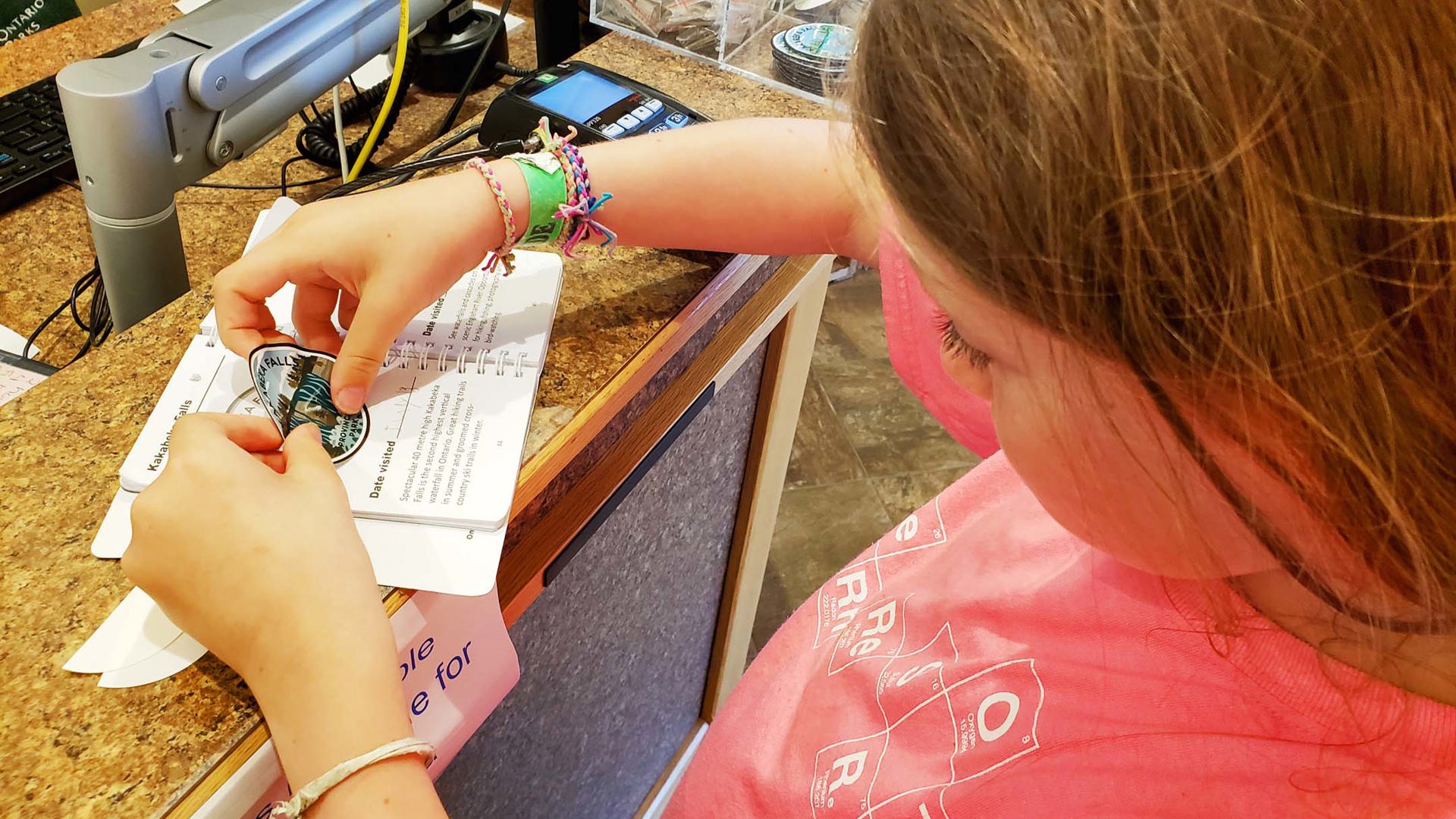

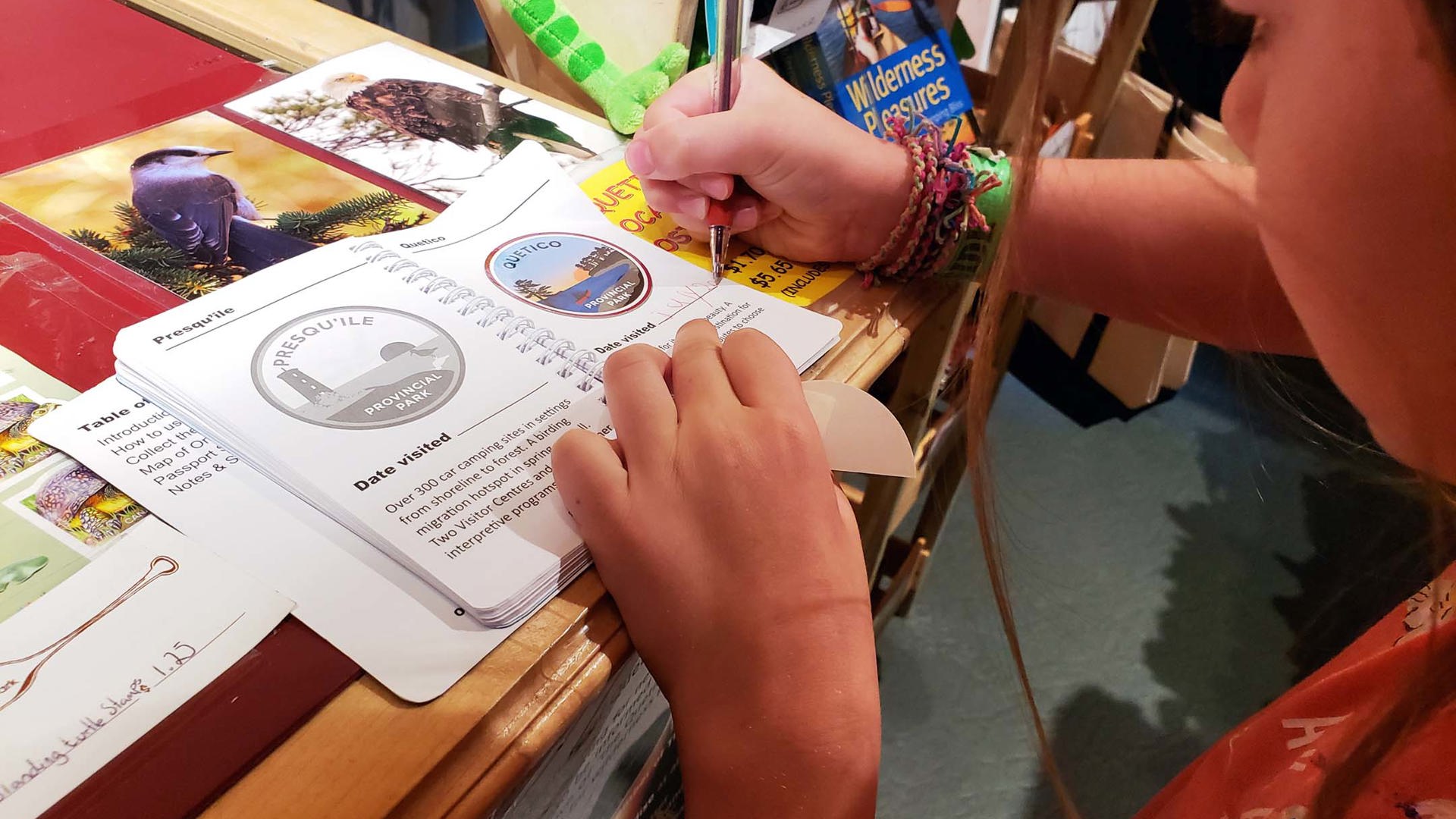

Along the way, we collected park crest stickers from each of the parks we visited and added them to our new Ontario Parks passport. My daughter loves looking through it, not only to remember where we’ve been but to map out where she’d like to go next. Parks crests are new for 2019 and are already helping us plan to get out and enjoy Ontario’s natural spaces.

DAY 6 – Kakabeka Falls to Rainy River

I expected the Hearst-to-Nipigon leg to be tough, but I didn’t know that the 320 km between Kakabeka Falls and Fort Frances would be equally unexciting. Our reprieve came through another unplanned lunch stop, this time at Quetico Provincial Park. We lingered longer than planned thanks to a geology drop-in program for kids and a great day use area with quality swimming.

Back on the highway, once you’re approaching Rainy Lake, before long you’re passing over it via the Noden Causeway, a 5-km series of bridges that uses islands as jumping points. And then you’re in Fort Frances, a typical Northern Ontario town but for one exception: inside the Safeway, there’s an honest-to-goodness Starbucks.

To the west of town, the Canadian Shield recedes and briefly gives way once again to agricultural lands, this time tracing the banks of the Rainy River as it edges toward the United States border.

And finally, 1,896 km later, we land in the village bearing the same name and our journey comes to an end.

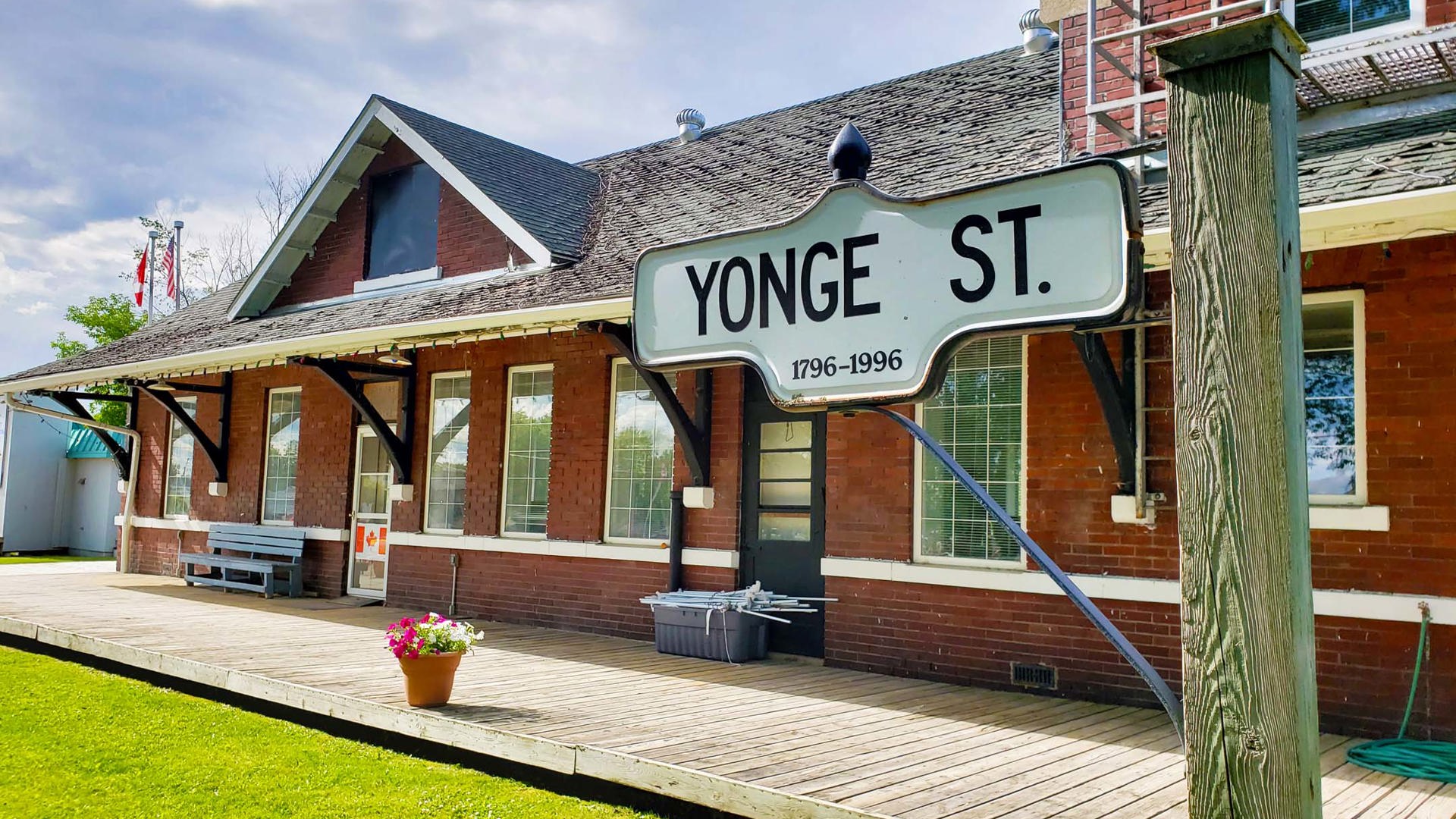

Honestly, the arrival is a little anticlimactic. Rainy River is a tiny border village that happens to have lofty bragging rights as the terminus of the longest street in the world. There’s some signage to that effect, along with a small railway museum housed in an actual engine, car, and caboose. Some intrepid tourists stop for pictures with the very average-looking sign that marks the end of Highway 11, and then they move on, while life here carries on largely unabated in its quietude.

But Is It Really the World’s Longest Road?

Or if it’s not today, was it ever? I can’t find a straight answer.

The City of Toronto website still hosts a claim to this effect, though it’s muted by admissions of doubt. The Guinness Book of World Records retained an entry for this until 1999, after which point the Province of Ontario downloaded many highways to municipalities and made the delineation between Yonge Street and Highway 11 more stark.

On the other hand, several sources state that the world’s longest road claim was born of a conflation of the two roadways anyway and that the entire concept was a myth from the start.

Cameron Bevers is a project manager for the Ontario Ministry of Transportation. He may very well hold the distinction of being the only person alive to have driven every one of the 21,500 km of the provincial highway network. (The author also owes Mr. Bevers a debt as his consult was invaluable in compiling many of the facts cited in this article.)

Bevers is intimately versed with the malleability of Yonge Street and Highway 11 over its decades of existence. What does he think of this claim that Yonge Street is the longest road in the world?

“Unfortunately, I can’t really provide any comments on the ‘longest street in the world’ claim,” he said. “I’m not even sure who was the first to make this claim, although it has certainly been a long-standing one. I recall being told this even as a kid, and admittedly, that goes back quite a few years now!”

In other words, there’s a lot of latitude here to believe what you want to believe. Either way, the mark that these roads have left on settlement, commerce, and industry is an indelible part of Ontario’s history.