Photos by Stephanie and M. Wallcraft

Enter Manitoba along Highway 1 from the east, and one of the first landmarks you’ll encounter is a large roadside billboard proclaiming that you’ve reached the centre of Canada.

It takes a fair while to get there. It’s more than an hour from the Ontario border, and from the road tripper’s perspective, there’s not a whole lot to write home about in between.

Yet, in a way, the fact that the centre of Canada is right here is poetically emblematic.

Following the literal sense, this really is Canada’s heart: 96° 48' 35" W is the longitudinal point from which it’s just as far to the westernmost point of the country, in the mountains of Yukon’s Kluane National Park, as it is to its eastern extreme at Cape Spear, Newfoundland.

But there’s a whole lot of figurative heart in this place, too. This was the second leg of the road trip my daughter and I took in the 2019 Chevrolet Colorado ZR2, towing a 19-foot 2017 Airstream Flying Cloud provided for review by Can-Am RV in London, Ontario. Along the way, we learned a great deal about this province: that the “Friendly Manitoba” moniker on its licence plates is far from hyperbole; that it holds plenty of tales about the many and diverse people whose families have called it home – including, as we discovered, our own.

And that the rest of us should stop treating Manitoba like a flyover province and start paying it the attention it deserves. There are so many places in this country that we celebrate for their distinctiveness, but the wide open spaces between the centre of Canada and the 100th meridian, where the great plains begin – which also cuts through the province along a line that bisects it just west of Brandon – are a part of Canada unlike any other.

Winnipeg: For Millenia, a Meeting Place

This is bound to come up, so let’s head it off at the pass: Yes, Winnipeg still has high rates of crime relative to the rest of Canada, and the vast majority of incidents are in the neighbourhoods immediately within and to the north and west of the downtown core. That said: crime in the city has come down significantly since 20 years ago, when Winnipeg earned a reputation it hasn’t been able to shake; a ton of investment has been made in improving the areas that draw tourism over the last five years or so; and every city has its rough spots, no matter how nice or clean or affluent it is. Others may have different experiences, but we practiced the same street smarts we would in any urban area – don’t leave cars unlocked or parked in shady places, walk in open and busy areas, and be aware of your surroundings – and, having had no issues at all, we enjoyed every minute of our time here.

The hub of Winnipeg is The Forks, the point of confluence between the Red and Assiniboine rivers, where First Nations people have been meeting in trade and celebration for 6,000 years or more. Today, its role as a meeting place continues: the area is home to a market, multiple outdoor spaces for festivals and concerts, a large park with a playground and a splash pad, and a massive indoor food hall with dozens of local restaurants – where, fittingly, we followed the tradition of The Forks ourselves by meeting some local friends for lunch. In winter, the space features tobogganing and skating on an Olympic-sized rink and a trail created on the Assiniboine River.

At the north end of the grounds, the Canadian Museum for Human Rights is a beautiful, thought-provoking, deeply challenging, and quite literal walk from darkness to light along the path toward equality for all. A visit begins in the lowest levels, which are styled from the outside to look like tree roots and on the inside are bereft of natural light. As the visitor moves into the galleries, an upward timeline of progress takes shape as ever more sunlight begins to stream in through the curved exterior windows, designed to simulate clouds swirling around the 100-metre Israel Asper Tower of Hope. Every aspect of this place, from the architecture to the enlightenment it provides, is a work of art in its own right. I’m especially grateful for the many interpreters in the galleries who are there to help families navigate content so that children can be introduced to these concepts at an age-appropriate level.

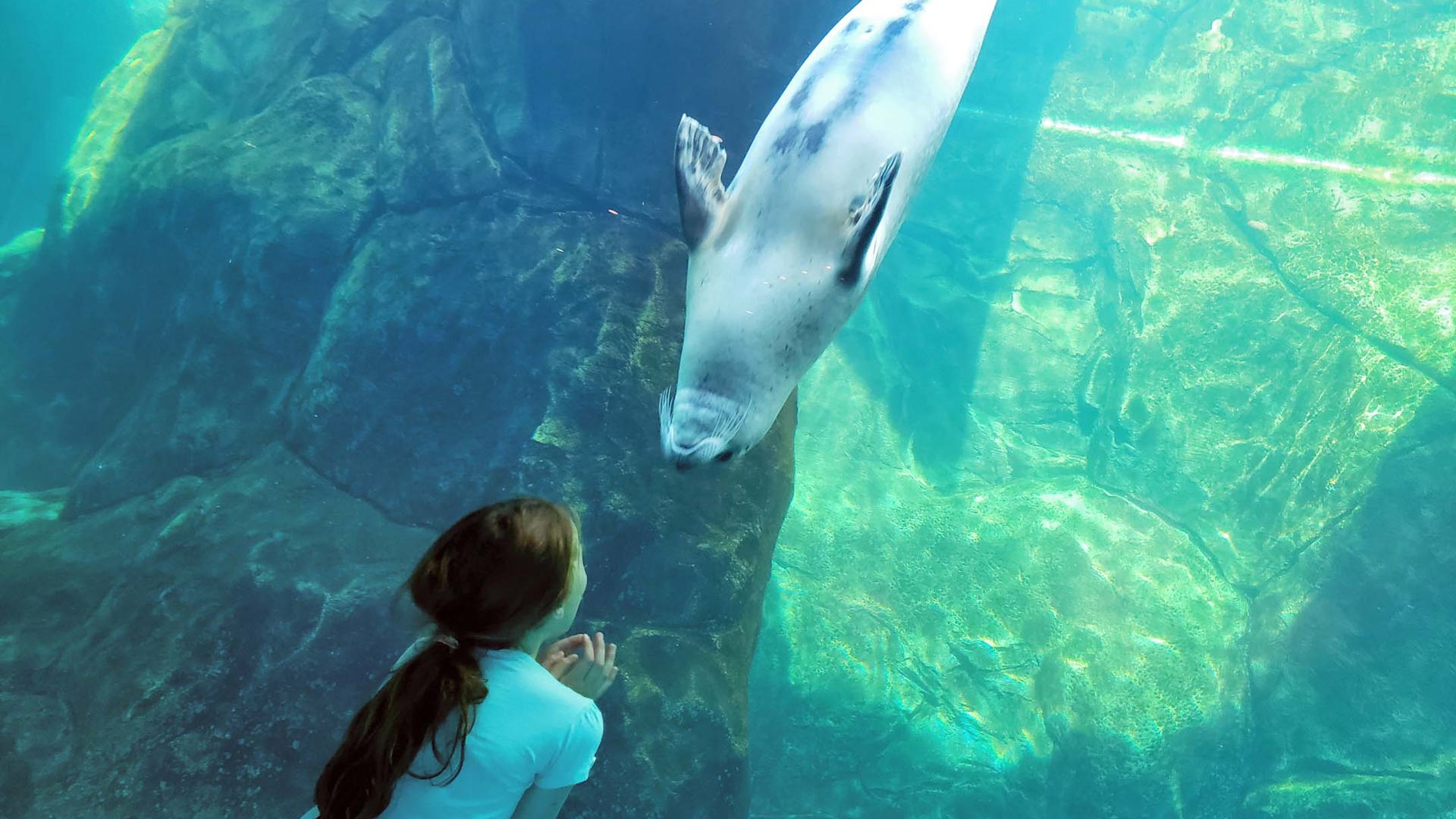

Tracing the riverbanks further to the west, the Assiniboine Park Zoo’s Journey to Churchill exhibit offers a concise and well-considered glimpse into the wildlife of Manitoba’s far north, including the risks being presented by climate change. The polar bear enclosure is the centrepiece, but the star of my daughter’s show was the harbour seal tank, where the seals swam in joyful cartwheels and seem to delight in interacting with visitors.

There are two Parks Canada National Historic Sites in Greater Winnipeg that take part in the kid-oriented Xplorers program, which means we inevitably had to pay them each a visit to add to our tag collection. (The Forks is also listed on the Xplorers website, but the staff there say their program is still under development and should be in place by the summer of 2020.)

Lower Fort Garry National Historic Site is located on the western bank of the Red River, just over a half hour north of downtown near Selkirk. Parks Canada protects numerous former Hudson’s Bay Company trading posts across the country, but this one’s size and scope makes it exceptional. Many of the original buildings dating from the 1830s still stand on the site today under careful restoration, and every one of the interpreters interacts with visitors in character to provide a truly immersive experience. We watched blacksmiths forge nails, learned how to spin wool into yarn, and spent nearly half a day gaining a vivid picture of what life would have been like for the Europeans and First Nations people who traded here two centuries ago.

Riel House National Historic Site is a fair bit smaller. Found in the south end of the city, this was the family home of Louis Riel, the man remembered as the founder of Manitoba and leader of two rebellions against the Government of Canada in defence of Métis rights. Though Riel himself never lived in this modest house, his mother and siblings did, and it’s preserved today in a state of mourning as it might have looked in early 1886 after Riel was executed for treason. This place offers an important reflection on the history of this region and its people, but it’s a quick stop: after an hour, we felt we’d taken it in appropriately.

Riding Mountain National Park: A Trip Back in Time

When it was time to leave Winnipeg, we set out again to the west along the Trans-Canada Highway toward Riding Mountain National Park, which lies roughly three hours to the west. We didn’t take the most direct route, though: we stopped to give our respects to the Halfway Tree, a landmark the locals consider the midway point along the TCH between Winnipeg and Brandon, and then continued through Brandon so that we could reach the 100th meridian and drive back through town blasting the Tragically Hip’s At the Hundredth Meridian with the Colorado’s windows down, as one does.

Once we finally got around to turning northward, the landscape began to change: over time, fields gave way to hills and dry grasslands to forested lakes. And then we crossed the park boundary and arrived at the townsite of Wasagaming, and it was as though we’d been transported back in time.

Riding Mountain still operates much as it might have when it opened in the 1930s, back when national parks were more about entertaining tourists than conservation. Wasagaming is set on Clear Lake, which has many things often found in a national park: boat rentals, a playground, a beach, and a large campground within walking distance of it all. But it also has a resort town vibe with motel and cabin accommodations, eateries, shops, tennis courts, mini golf and more. Of the few parks left in Canada that still operate this way, this is the most tranquil and least overrun with people and multinational brands that I’ve encountered.

The park is also home to a bison enclosure near Lake Audy, roughly 45 minutes to the west of Wasagaming. Not far from the townsite is the trailhead for a day hike to one of Grey Owl’s cabins, where the conservationist lived for six months before relocating to Prince Albert National Park in Saskatchewan.

And on its eastern boundary, the East Gate Registration Complex is of historic interest as the country’s last remaining 1930s-style National Park entry gate. Getting to this is a bit of a trick, though. If you have a suitable vehicle, you can take Highway 19 through the park. However, it’s very tight, twisty, and unpaved. I was advised by park staff that I’d regret attempting to negotiate it with my truck-and-trailer combination, and we weren’t there long enough to justify disconnecting the Airstream, making the round trip, then returning to the campsite to pick the trailer up.

So, we drove around instead, taking Highway 10, Provincial Road 357, and Highway 5 to join Highway 19 at its eastern terminus and access the gate from the other direction. It’s a lot of work to look at a wooden structure for a few minutes, but it is a cool thing to see: there’s not another one like it left anywhere in Canada.

A Personal Manitoba Connection

I discovered one more surprising detail in Manitoba: a family history that I thought was lost to time.

Three summers ago, my best friend and I and our two daughters took a road trip to her home province of Newfoundland and Labrador. When we drove into her mother’s home village, my friend walked into a gas station to ask for directions and met a cousin she never knew she had.

I was envious at the time because I was confident this was an experience I would never have myself. My surname is so uncommon that my extended family was sure we already knew everyone on the continent to whom we’re related.

Fast forward a little more than a year, and my father has just returned from a road trip out west that he and his partner decided to take last-minute. He’s flipping through vacation photos and is raving enthusiastically about some distant relatives he met in Manitoba. I look and listen, filing it all away as something to ask follow-up questions about later because – as children have a horrible habit of doing – I assume I have all the time in the world.

A few months after that, my father is gone. And over time, it starts to dawn on me that a wealth of knowledge about our family history went with him. But as far as I know at the time, it’s still there in Manitoba, waiting to be found once again.

And I know now that I don’t have all the time in the world. I have another generation to educate.

So, I start dredging up what information I can recall. Dad mentioned a Google search that sent him to the Pembina Valley, though I can’t remember how he came across it. (My uncle, his youngest brother, later fills in this gap: Dad saw someone he didn’t recognize on an episode of the CBC series Still Standing who shares our surname. That had never happened to him before, so it piqued his curiosity.)

I make the same search myself and come up with a destination. With little else to go on apart from a scant few names and photographs, my daughter and I find ourselves lumbering along a single-track gravel road with little clue of what we’ll find when we get there.

We reach the address in our search and find nothing but a cluster of long-abandoned buildings. Crestfallen, I turn around to get back into the Colorado – and spot a cairn on the other side of the road that I’m sure I’ve seen before.

On it, a plaque commemorates a century of farming in this location… by the Wallcraft family.

We can hardly believe our eyes. And then I realize why I recognize this place: Dad was here! He showed me a photo. And then I can hear him recounting what he did once he found it: he hadn’t known what else to do, so knocked on the front door of the house on the corner to see what would happen.

So, I knock on the same door – and I meet a cousin I never knew I had.

She welcomes us warmly, and then I ask after the names I can remember. Those are my in-laws, she says, and she sends us another mile up the road. We walk up to another door and are invited inside before we have a chance to knock.

I turn a corner to greet the first blood relative I’ve met in decades – who looks so much like my father that I stop in my tracks.

We enjoy a truly wonderful lunch and visit. Shortly afterward, I revisit a few scanned pages from a local history book that Dad received when he came through here. It turns out that an ancestor settled on this very land with his family after emigrating from the United Kingdom in 1878, lured by the government’s promise of free land.

Now, I know that my daughter is a seventh-generation Canadian, and she can say that she has stood on the land where our family set down its roots in this country. And it’s all because my father chased down a curiosity and knocked on a door.

This is our story, but it really is just one among millions. So many families share a history in Canada that’s nearly identical to ours, and others may have lost touch with theirs just as we had. Or some of us may be descended from First Nations people who have been here for as long as time can remember, or some may be Canadians who are just beginning their stories after stepping off a plane a few days ago. Over time, every story becomes interwoven with the others to form the profoundly diverse tapestry that is Canada.

I’m delighted to have reconnected with our family’s thread. Perhaps this recounting might inspire another family to do the same, whose story is still out here on these plains, miles up a single-track gravel road, waiting to be rediscovered.