Imagine painstakingly creating your mechanical masterpiece, and then having some of the world’s best engineering minds relentlessly refine that masterpiece for the next six decades. That is the story of Porsche’s seminal 911.

What has become the world’s most recognizable automotive icon was first presented to the world in 1963 as a successor to the 356 series, the cars that first made Porsche a household name and one synonymous with impressive performance despite their small size. The 911 (originally billed the 901 before Peugeot claimed trademark foul) was a larger, more usable coupe than its forebear, but would retain the air-cooled, rear-engine layout Porsche had been perfecting for decades.

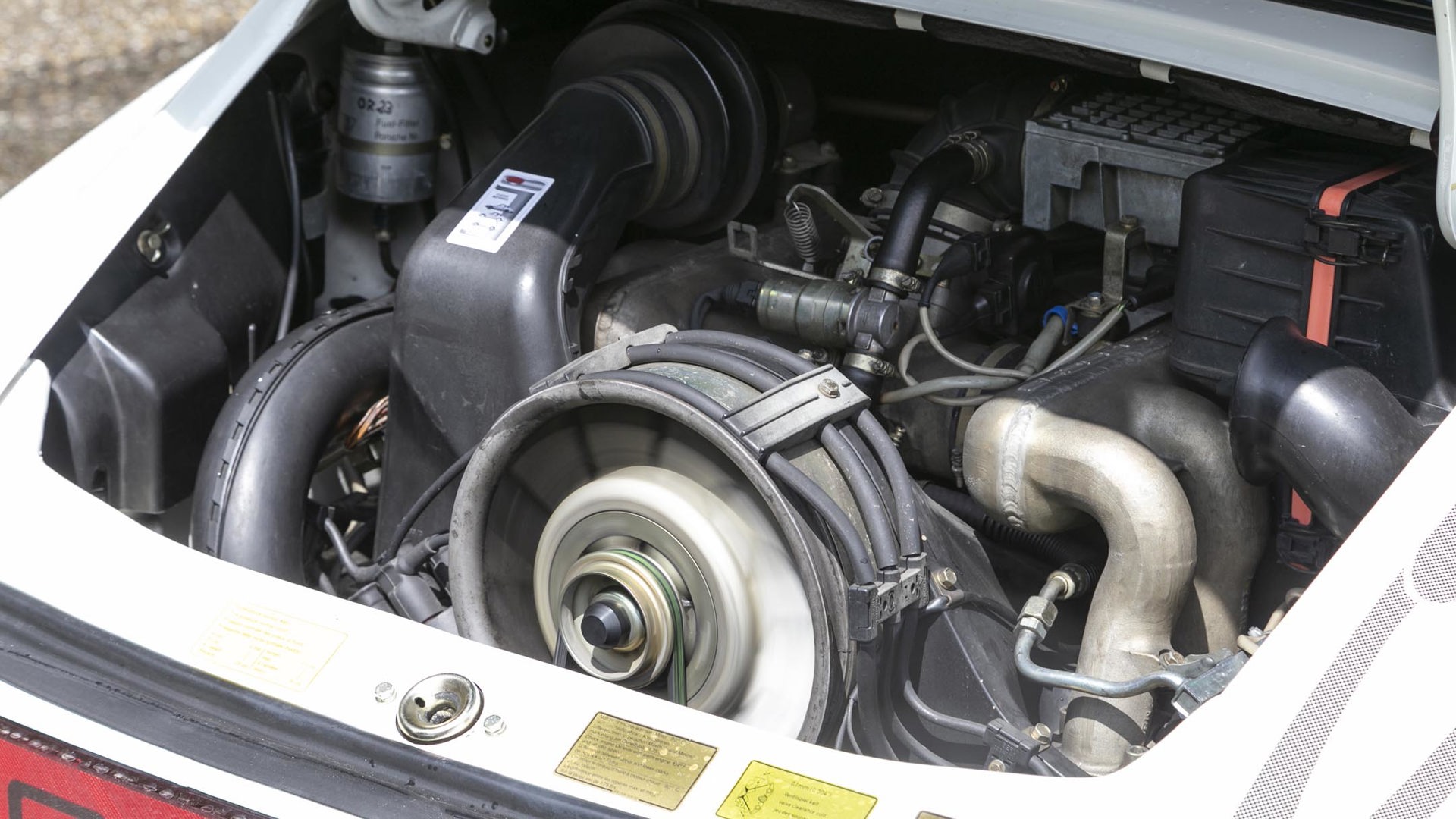

Since that original 911’s 2.0L flat-six engine, the displacement has grown (in fact, as much as doubling to 4.0L in some variants), and we’ve seen a shift from air-cooled to liquid cooling, the implementation of all-wheel drive, and standard turbocharging, but despite it all, the rear-slung flat-six remains the heart and soul of the 911.

Rich in History

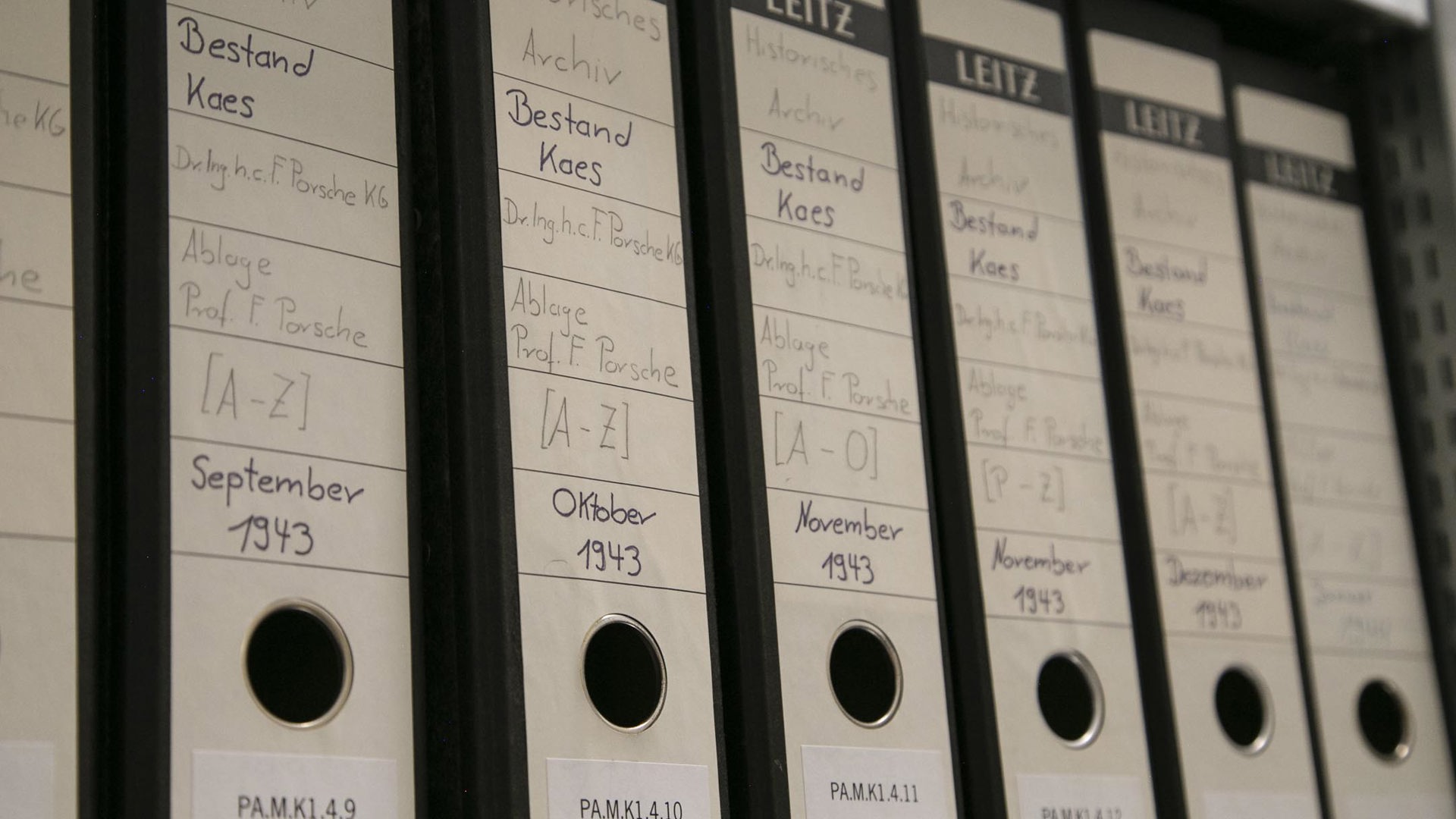

A visit to the Porsche Museum should be on any car enthusiast’s bucket list where the modern architectural expanse presents some of the marque’s most significant road and racing machines amongst its ever-changing exhibits. Housed upstairs is Porsche’s corporate archives that contain a dizzying collection of historic corporate artifacts, an extensive library, and countless pieces of interesting paraphernalia. Granted a private tour, I confess to nerding out over Dr. Porsche’s handwritten notes dating back to the 1930s, design studies for various models, and even the original drawing of the Porsche crest.

With my mind swimming from the historic immersion, the best was yet to come, as the museum graciously turned over the keys to three different generations of 911 to compare against a new Carrera 4 for an incredible celebration of 60 years of the 911 from behind the wheel.

I’ve been lucky enough to drive 911s from several generations, in a number of different trims and yet the four cars on my docket were variations I had never previously experienced, including one very special car. I’m a kid from the ’80s, so while I appreciate the cars from the ’60s and ’70s, the four newer generation 911s offered could not have been more meaningful to me.

993 Targa (1995)

As the last of the water-cooled Porsches, the 993-generation screamed up in desirability and value well ahead of the 964 and G-series predecessors. Beyond their last-of-the-kind drivetrain, 993s are also considered among the prettiest of 911 generations, still possessing the classic shape and scale, but with modern, smoothed corners. For me, it was the hours spent playing the first Need for Speed game in the mid-’90s that imprinted this one in my brain.

In 1995, Porsche revived the Targa name that had been parked for several years. Where previously Targas featured a removable roof panel, for the 993 it meant an elaborate glass roof panel that slid electrically down in front of the rear window, providing an open top. In practice, it was a complex system tacked on to a 911 Cabriolet body that created a weird rearward visual experience when looking through the doubled-up panes.

Paddle shifters are found in everything from econo-boxes to minivans these days, making it hard to remember when Porsche’s Tiptronic was cutting edge. Driving this Tiptronic-equipped 1995 model exemplifies just how far automatic transmissions have come since there were quaint up- and down-shift toggle buttons on the steering wheel. Between making do with only four gears, and the woefully soft, sluggish responses, the Targa’s slush box seriously depletes most of the fun and personality of this car. Navigating Stuttgart’s traffic and cruising down a rain-soaked Autobahn did have me appreciating the classic air-cooled soundtrack, and how solid and stable the car is even at elevated speeds.

996 Carrera 4 Cabriolet (2001)

As much adulation is heaped upon the 993s, its successor, the 996, is often derided as the unloved generation of the 911, yet both are somewhat undeserved. The 996 is the historic point when the 911 truly entered modernity. It grew in size both inside and out, and for the first time, Porsche began parts-sharing across models, giving the 911 a lot more in common with lesser models (in this case, the Boxster) than before. By modern standards, its interior finishes are admittedly pretty chintzy, but even with over 100,000 km showing on the clock, this convertible was in appropriately museum-quality condition.

Besides the odd “runny egg” headlights, many self-proclaimed purists felt the 911’s shift to water-cooling was the 996’s biggest fault, somehow causing it to give up its soul and personality. The fearsome and well-documented concerns of intermediate shaft bearing failures grenading engines has also done no favours for 996 popularity. For many would-be 911 owners of rather limited means (yours truly included), this is both a blessing and a curse since it has kept 996 costs reasonable, but owners will need to live with the knowledge that their car is considered somehow unworthy of the 911’s vaunted reputation.

The 996 I drove was obviously a well-sorted example and it provided the biggest surprise of the day. Now more than 20 years old, it provides a level of driver engagement missing from all but very few modern cars. The steering is wonderfully direct and responsive, and being an all-wheel drive Carrera 4 model with modern tires, its sensational grip in the corners and strong 3.6L flat-six meant I had no trouble nipping at the heels of the new 992 Carrera 4 as we zipped from hairpin to hairpin. But it’s also modern and refined enough to be comfortable when puttering around town, or cruising down the highway, reaffirming my belief that even the least desirable 911 is still a far better car than most.

992 Carrera 4 (2024)

It’s tough to find fault with the current-generation 911. They maintain the unmistakable profile and their performance continues to push boundaries, especially in the monstrously powerful Turbo S and GT models. Even in relatively basic spec, like this test car, they’re far more polished and decadently finished with richer materials than earlier 911s. But of course, they’re also far more expensive than ever before, and despite starting at “only” $139,100 for this car, after more than $30,000 in options, fees and luxury tax, it pushes perilously close to $200,000.

The level of sophistication, solidity, and refinement of the new car shows just how far the 911 has come in its most recent two decades, let alone since the mid-’60s, and yet, it’s still more of a driver’s car than almost any other new machine on the road. While the increased sound deadening, that flat-six growl still contributes greatly to the experience, but it is bigger, heavier, and refined almost to a point where some of the fizz of the earlier cars has now been filtered away.

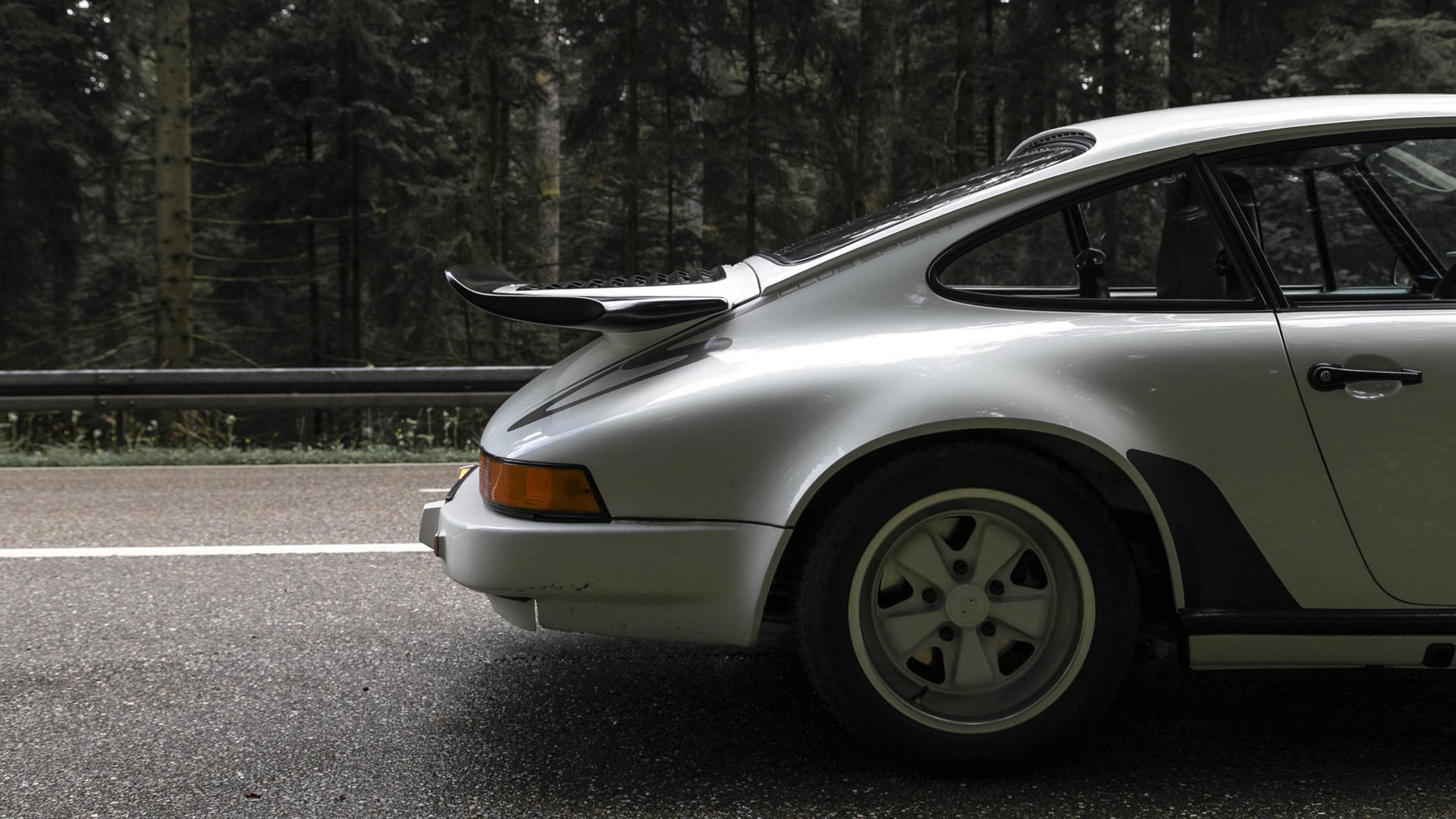

911 Carrera 3.2 Coupe Clubsport Prototype (1985)

The ’80s-era G-series 911 is the generation forever cemented in my brain as the archetypal Porsche. The tiny, frog-faced coupe blends the best of the original look and admittedly archaic interior of the early 911s, while gaining just enough performance to keep them relevant in their day. What’s more, they’ve established a reputation for having been completely over-built, meaning owners can (and have) used them as daily drivers, sometimes accruing a lot of kilometres, and they still keep happily running. Where other Euro sports cars of the era might’ve been relegated to occasional status due to their fragility and cantankerous unreliability, the Carrera 3.2 is no garage queen.

With only 40,000 km on it, this fully-restored 3.2 is a particularly special representation, having been built in 1985 as a pre-cursor to what would be the short-lived ’87-’88 Clubsport production model, of which only 189 were produced.

Like many special performance edition 911s that came before and since, 3.2 CS had been significantly de-contented, giving up its air conditioning, radio, power windows, and locks, the rear seats, and even the right-side sun visor in the interest of lightening the car. In addition to the 100-kg weight loss, there were lighter intake valves, special pistons, and connecting rods, enabling it to spin up to a 6,840-rpm redline (320 more than the standard 3.2). Special shocks resulted in a 30-mm lower suspension and a limited-slip differential finished off the package. Lifting the rear deck-lid, I was shocked at how thin and flimsy it felt, even with the whale tail attached.

It’s the absence of sound-deadening materials that really helps this car feel exceptional. From the moment the ignition fires up the engine, there’s a sensational gruff, mechanical cacophony helping to envelop the driver as much as any car can into the internal combustion process. The un-boosted steering gets heavy when slowing for tight hairpin turns, but the feel is unmatched by modern machinery. Every harmonious meshing of gear teeth is shared with the driver, who’s lucky enough to conduct this exhilarating production of careful gear selector movements, muscle-building steering, and floor-hinged pedal dancing.

Admittedly, I approached this car with caution, not only due to its obvious value, but because it was a raw and presumably unforgiving mechanical beast from a time in Porsche’s history when 911s were known as the Doctor Killers. Legend has it that many an affluent owner pushed beyond their driving skill only to experience the snap-oversteer that sent them careening over a cliff to their demise.

But this car didn’t want to kill me, instead behaving as if it knew how much I loved (and respected) it, and it obediently and playfully roared up and down through its gears, chasing its newer cousins through the thick forest roads. Overthinking it wasn’t the answer, since it’s a car that rewards a pilot who learns its quirks and limitations and relishes exercising it up to that point, but not beyond. Porsche claimed the Clubsport would do the sprint to 100 km/h in 6.1 seconds, which was appreciably quicker than its contemporaries, but easily the slowest car I’d drive that day. It was also, by far, the most exciting; the most exceptional, and certainly my favourite car.

There is No Substitute

Engineering a car to not only be fast, but durable and useful makes for a truly great machine. Early galvanizing made 911s viable for four-season use, while the vestigial back seats have served as extra storage and a way to help reduce insurance costs, if not actually fit for human use. It all makes for a one-of-a-kind car.

Over the years, critics have scoffed at Porsche’s stubbornness to stick with what appeared to be an obviously flawed design hanging that heavy engine out in the back there. But time, tinkering and engineering excellence have not only helped the 911 endure long past anyone’s expectations, but have transformed it from an interesting and capable – if challenging – sports car, into a truly awesome one. And that had already happened by the 1980s. In the 40 years since then, the world’s longest-lived and most famous sports car has only continued to evolve and exceed expectations.

Happy Birthday, 911. Here’s to 60 more exciting years.